Propublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates power abuse. Sign up and receive the biggest story as soon as it’s published.

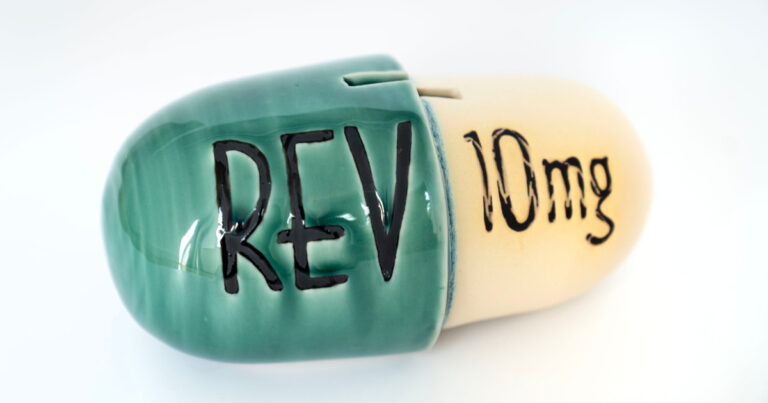

In the US, prices for the brand-name cancer drug Revlimid have been rising for 20 years. It is currently on sale for nearly $1,000 per tablet. Prices are consistently low in Europe. In some countries, this is up to two-thirds.

After being prescribed medication following the diagnosis of multiple myeloma, an incurable blood cancer, I began reporting on Revlimid. Surprising at the high prices, I discovered that drug maker Sergen has been using Revlimid as its own piggy bank for over a decade and raises US prices whenever it is properly seen.

Even with low prices in Europe, Celgene still made a profit there, a former executive told Congress. It added to the company’s over $21 billion net profit after Revlimid was introduced in 2005.

Of course, Revlimid is not the only drug with a price gap. Americans generally pay for prescription drugs than people in other wealthy countries. And costs continue to rise, forcing patients to undermine their debt, fill their prescriptions, or choose to buy grocery. So why do we pay so much? And is there anything going on about it?

Remission price

In most other wealthy countries, governments usually set a single price for a drug based on an analysis of the therapeutic benefits of the drug and what other countries pay. In the US, pharmaceutical companies decide what to charge for products that are rarely bound. Insurance companies can refuse to cover drugs to try to negotiate a lower price, but in the case of illnesses like cancer, it poses a risk of public repulsion. Cancer is “a very politically charged disease,” says Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard University who studies drug pricing and regulations. Some states require insurance companies to cover certain cancer drugs.

Pharmaceutical companies have consistently argued that US drug prices reflect the costs of research and development. Americans may pay more, but they also benefit from first access to cutting-edge treatments. (Celgene was subsequently acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which states that Revlimid’s price, which rose 7% in the US last year, “the clinical benefits it brings to patients along with other economic factors will provide continued clinical benefits.”)

Dr Hagop Cantaldian, a leukemia expert at MD Anderson Cancer Center, who studies drug pricing, said pharmaceutical companies often exaggerate the cost of drug development, and many drug discoveries occur in academic laboratories funded through hospitals and government grants. According to a study by Bentley University, funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health contributed to all but two of the 356 drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration from 2010 to 2019. And, a 2021 analysis by the U.S. House Oversight Committee found that businesses don’t spend all their profits on innovation.

One possible solution to reducing costs is to tie American prices to what drugmakers charge in other wealthy countries. The Congressional Budget Office discovered last year that this had the biggest impact on reducing the costs of the seven proposals it examined. It’s a bipartisan support idea.

R-Mo. Senator Josh Hawley and D-Vt. Peter Welch of Canada introduced a bill this week to punish pharmaceutical companies selling drugs at higher than average prices in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Italy and the UK. Companies selling above average face civil penalties that amount to ten times the difference between US price prices and average prices in other countries.

President Donald Trump advocates similar actions. During his first term he issued an executive order directing Medicare programs to adopt a “most preferred country” approach to drug payments. The administration later developed rules that would select the lowest prices from a basket of similar countries and direct Medicare to create the maximum amount that agents would pay for the 50 drugs administered by doctors. The court prevented the rules from being implemented on the last day of the first administration.

Now, this week’s report, the administration is pushing for plans to lower prices charged for Medicaid and Medicare in other countries.

Linking US prices to prices in other countries has been opposed by industry groups that say it leaves the drug decisions behind governments rather than doctors and patients.

“All forms of government pricing are bad for American patients,” said Alex Schriver, spokesman for American pharmaceutical research and manufacturers, an industry group. He said the focus should be on fixing “flaws in the US system,” including money flowing to intermediaries such as pharmacy benefits managers.

Some critics also warn that so-called international reference pricing will be covered in games, allowing foreign governments to essentially set the value of medicines sold in the US.

Reports say the Trump administration is scheduled to announce its drug pricing plans as early as next week. The White House did not respond to requests for comment.