Connor here: French media reported yesterday that two suspects from the impoverished Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis were arrested and may have been helped by Louvre security guards. There’s no word on what happens to the Crown Jewels, and some gasp, comparing its loss to the Notre Dame Cathedral fire in 2019.

It’s entirely possible, if unlikely, that the thieves were working for very wealthy “collectors,” as commenters discussed on Links shortly after news of the Louvre’s hesitation broke. If all they’re after is jewelry and gold, it seems like there are easier, less obvious targets. In the next article, we will discuss the trade in stolen art in more detail.

Written by Leila Aminedrei, Adjunct Professor, New York University School of Law. Originally published on The Conversation.

The high-profile robbery at the Louvre Museum in Paris on October 19, 2025 unfolded like a scene from a Hollywood movie. Thieves have stolen a dazzling array of royal jewels on display at one of the world’s most famous museums.

However, the robbers still have work to do as the authorities are pursuing them aggressively. How can I use what I have stolen?

Most of the stolen works have never been found. In the art crime course that I teach, I often point out that the arrest rate is less than 10%. This is especially alarming given that between 50,000 and 100,000 works of art are stolen each year around the world. The real number may be much higher due to under-reporting, with the majority being stolen from Europe.

However, it is actually very difficult to make money from stolen art. However, the type of items stolen from the Louvre – eight pieces of valuable jewelry – may give these thieves an advantage.

narrow buyer’s market

Stolen paintings cannot be sold on the art market because the thieves are unable to convey so-called “good title,” meaning ownership that belongs to the legal owner. Additionally, reputable auction houses and dealers will not knowingly sell stolen art, nor will responsible collectors purchase stolen art.

But that doesn’t mean stolen paintings have no value.

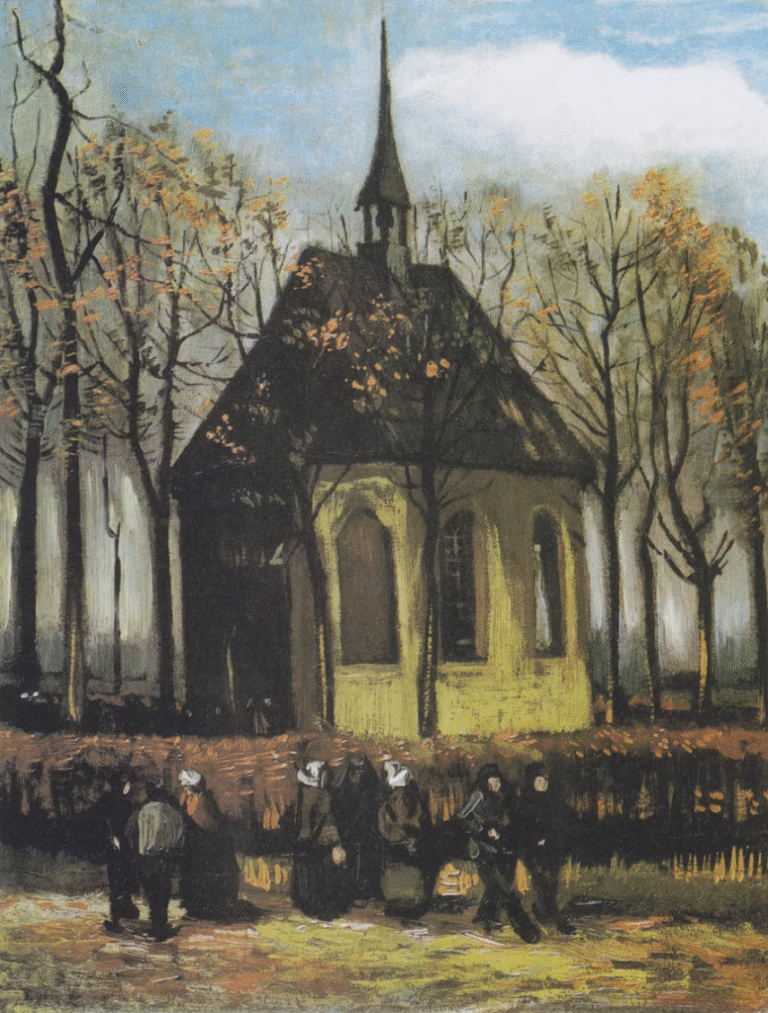

In 2002, thieves broke into the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam through the roof and left with the “sea view of Scheveningen” and the “congregation leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen.” In 2016, Italian police recovered relatively intact art from a Mafia hideout in Naples. It is unclear whether the mafia actually purchased the artwork, but it is common for criminal organizations to hold valuable assets as collateral of some kind.

Van Gogh’s 1884-1885 oil on canvas painting “The Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church of Nuenen” was one of two works by Van Gogh stolen from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2002.

Also, stolen works sometimes end up in the hands of collectors without their knowledge.

In the 1960s, Guggenheim Museum employees stole a Marc Chagall painting from storage in New York City. But the crime wasn’t even discovered until an inventory was taken several years later. Unable to locate the work, the museum simply removed it from its records.

Meanwhile, collectors Jules and Rachel Rubel purchased the work from the gallery for US$17,000. When the couple asked the auction house for an estimate on the painting, a former Guggenheim employee at Sotheby’s recognized it as the lost painting.

Guggenheim demanded the painting’s return, and the court dispute ended. The parties eventually settled the case and the painting was returned to the museum after an undisclosed amount was paid to the collector.

Some people knowingly purchase stolen art. Buyers were well aware of the popular looting that took place across Europe after World War II, and stolen works appeared on the market.

Eventually, international laws were passed that gave original owners the opportunity to recover stolen property, even decades after the fact. In the United States, for example, the law even allows descendants of the original owner to regain ownership of stolen works if they can provide enough evidence to prove their claim.

Monetizing jewelry and gold becomes easier

However, the Louvre theft did not involve any paintings. The thieves made off with jeweled property. A necklace and earring pair set related to 19th century French queen Marie Amélie and Hortense. A gorgeous set of earrings and necklace that belonged to Empress Marie Louise, Napoleon Bonaparte’s second wife. diamond brooch. and Empress Eugenie’s crown and corsage ribbon brooch.

Finely crafted over centuries, these pieces have unique historical and cultural value. But even if each were broken into pieces and sold for parts, they would still be worth a considerable amount. Thieves may sell valuable gemstones and metals to unscrupulous dealers and jewelers who rework and sell them. Even if it’s only a fraction of its value, the price of looted art is always much lower than the price of legitimately sourced art, so jewelry can be worth millions of dollars.

Although it is difficult to sell stolen items on the legal market, an underground market for looted art does exist. Works can be sold in backrooms, private meetings, and even on the dark web, where participants cannot be identified. Studies have also found that mainstream e-commerce sites such as Facebook and eBay frequently feature stolen and sometimes counterfeit art and antiques. After the sale, the vendor may delete the online store and cease to exist.

The sensational charm of robbery

While movies like The Thomas Crown Affair feature dramatic heists with impossibly glamorous robbers, most art crimes are far more mundane.

Art theft is usually a crime of opportunity and tends to occur in storage or while the work is in transit, rather than in the heavily guarded halls of a cultural institution.

Most large museums and cultural institutions do not display all the objects they manage. Instead, they are stored in warehouses. Less than 10% of the Louvre’s collection is on display at any one time, making up only about 35,000 of the museum’s 600,000-piece collection. The rest can remain invisible for years or even decades.

Andy Warhol’s rare silkscreen painting “Princess Beatrix” was likely accidentally discarded along with 45 other works during the renovation of a Dutch city hall, and it is possible that works in storage were unintentionally left behind or simply stolen by staff. According to the FBI, about 90% of museum robberies are inside crimes.

In fact, just days before the incident at the Louvre, Picasso’s “Still Life with Guitar” worth $650,000 went missing while being transported from Madrid to Granada. The painting was part of a package containing other works by the Spanish master, but when the package was opened, the paintings were gone. This incident did not attract much public attention.

To me, the biggest mistake the thieves made was not throwing away their dropped crowns or discarded vests, essentially leaving no clues for the authorities.

Rather, the brazen nature of the heist itself captured the world’s attention and ensured that French detectives, independent detectives, and international law enforcement were on the lookout for new gold, gems, and royal jewels to be sold for consumption for years.