Written by Hjalte Fejaskov-Boas, PhD student in economics at the University of Copenhagen; Niels Johannessen, professor of economics and business at the University of Copenhagen; and Klaus Kleiner, professor of economics and director of the Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality (CEBI)) Lauge Larsen, University of Copenhagen (Doctoral student, Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen), Gabriel Zucman (Professor of Economics, Paris School of Economics). Originally published on VoxEU.

While the financial secrecy of offshore tax havens has historically created ample opportunities for tax evasion for the wealthy, automatic exchange of information between tax authorities is an ambitious attempt to enable tax enforcement. This column explains how information exchange can significantly improve tax compliance through audit efforts targeting the repatriation of offshore assets, self-reporting of offshore financial income, and offshore avoidance.

Over the past decade, more than 100 countries, including all important offshore financial centres, have introduced automatic exchange of banking information. We now systematically collect information on bank accounts owned by foreigners and automatically provide this information to the relevant foreign tax authorities. Information exchange involves personal financial assets held directly or indirectly through holding companies, trusts, etc.

The purpose of automatic information exchange is to curb offshore tax evasion, which is a key policy issue in a globalized world. Empirical studies show that personal wealth in offshore tax havens reaches trillions of dollars (e.g. Zucman, 2013), which overwhelmingly belongs to the wealthiest individuals (e.g. Alstadsæter et al. 2018a, 2018b, 2019) ), which, at least until recently, largely evaded taxation.

A recent paper (Boas et al., 2024) studies the impact of automatic information exchange on tax compliance. Our institute is located in Denmark and has created a unique data infrastructure that covers all 300,000 intelligence reports on foreign bank accounts received by the Danish authorities, and has tracked the incomes, assets and borders of approximately 5 million adults. The data is compared with microdata related to bank transfers. taxpayer.

repatriation

First, we ask whether automatic information exchange allows taxpayers with offshore bank accounts to repatriate assets and smooth transaction data on remittances from tax havens.

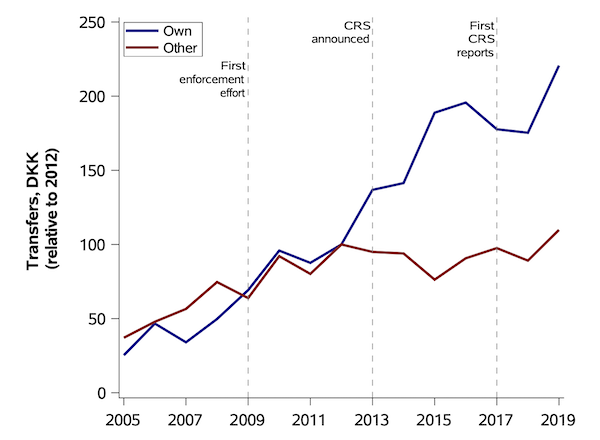

As shown in Figure 1, since 2013, remittances from personal accounts in tax havens (“repatriation”) have been differentially more common than other remittances from tax havens (“other remittances”). Increased. These are indicative of the strong repatriation reactions triggered by the upcoming G20 decisions. Automatically communicate new global standards and subsequent efforts to implement this decision.

Figure 1 Repatriation

We also document that repatriation from tax havens is associated with a 1:1 increase in total assets on tax returns and a commensurate increase in taxable capital income and tax liabilities. This means repatriation is from non-compliant accounts and comes with increased tax compliance.

self-report

We next considered whether taxpayers who did not repatriate their foreign assets were more likely to self-report financial income in their foreign accounts at the start of automatic information exchange.

As shown in Figure 2, we see a sharp increase in the number of taxpayers self-reporting foreign financial income on their tax returns, coinciding with the launch of automatic information exchange in 2016-2017. In fact, the number of self-reporters has roughly tripled in a short period of time.

Figure 2 Self-report

\

We interpret the increase in self-reported foreign financial income as a taxpayer response to the information exchange. To support this interpretation, we provide two types of evidence:

First, we consider separately cohorts of taxpayers treated at different points in time due to the gradual introduction of automatic information exchange between their foreign counterparts. In each cohort, the sharp increase in self-reporting coincides with the first year of information exchange. Second, document a clear self-assessment response to a letter from the Danish tax authorities informing the taxpayer that they have received an information report regarding foreign bank accounts.

This result suggests that a large number of taxpayers comply with their tax obligations through self-assessment, but the impact on revenue appears to be modest. This reflects that the increase in self-reporting is driven by taxpayers with lower levels of foreign financial income, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Self-reporting by foreign income range

]

Audit improvements

Finally, we study the extent to which offshore tax evasion can be more effectively detected in audits that target foreign financial income and leverage new information about offshore accounts.

We are working with the Danish Tax Authority to plan an audit effort to target a random subset of taxpayers for whom a comparison of their tax returns and foreign information reports suggests significant tax evasion. Specifically, all taxpayers whose interest and dividend income reported by a foreign bank exceeds the foreign interest and dividend income reported by the taxpayer in his or her own tax return by more than DKK 5,000 are subject to audit. Select 500 taxpayers.

The audit results allow new information reporting from foreign banks to estimate offshore tax evasion that tax authorities can potentially detect through this type of audit activity. Our results reveal that there is a significant audit potential, but it is small in magnitude compared to other impacts, potentially indicating that large amounts of money are already compliant through remittances and self-reporting. It is reflected in

discussion

Combining estimates from different empirical designs, we conclude that automatic information exchange has closed approximately two-thirds of Denmark’s offshore tax gap. Although repatriation appears to be the biggest contributor to improving tax compliance, improvements in self-reporting and auditing also play a role that cannot be ignored.

This suggests that automatic information exchange is a relatively successful approach to tackling offshore tax evasion. This is particularly true when compared to previous policy approaches that have largely failed (Oldenski et al. 2011, Johannesen 2014, Johannesen and Zucman 2014, Johannesen et al. 2020). However, compared to domestic third-party reporting, cross-border information exchange still leaves significant room for non-compliance (Kleven et al. 2011). In our paper, we discuss various possible explanations.

It is important to emphasize that our findings do not necessarily apply to other countries. In particular, developing countries with less capacity to process information reports from foreign banks may benefit less from automatic information exchange (Johannesen 2024).

References are available in original.