Individual interviews were conducted with nine participants in May – June 2023. The participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Using protean career theory as a framework, the following themes emerged.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants

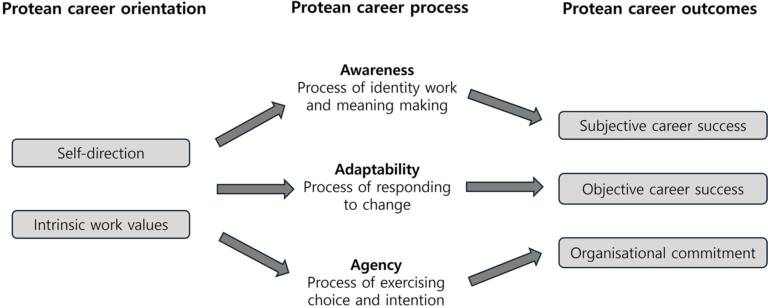

Protean career orientation

Protean career orientation is a career approach characterised by self-direction where individuals desire to be agentic, in control of their careers and value-oriented. Intrinsic values guide their career decisions [14]. Here, the person rather than an organisation or others, is in charge, leading to self-direction, that is, an individual’s independence from external control or influence [14]. An individual’s interaction with intrinsic values leads to career selection and transition, whereby, they actively create their meaning rather than adhering to externally defined meanings [14].

Self-direction

Participants’ self-direction in their career development was evident through their self-directed learning. Understanding the importance of continuous self-development for enhancing their expertise as medical educators, they have consistently engaged in self-directed learning:

‘I think the most important thing is the ability to identify essential educational issues and to learn the related educational principles on your own. I have always done that by studying through self-directed learning and teaching’. (Participant B)

The participants pursued self-directed learning by pioneering related study routes. Although they lacked external faculty development support, they pursued self-directed learning and growth as medical educators, gradually building academic expertise in the field. Specifically, they created self-learning opportunities by attending overseas conferences with limited support:

‘I wasn’t expecting that kind of support…Studying was something I could do by collecting resources on my own. I organised my schedule and went to educational conferences’. (Participant C)

Intrinsic work values

Participants recognised that the value of medical education lies in its ability to nurture physicians who provide compassionate patient care and contribute to society. They believed that medical education could ‘establish good doctors with real-world problem-solving ability, that is, humanistic and socially responsive, who are interested in “solving social issues”’ (Participant A). An understanding of these intrinsic values is crucial for sustaining a career as a medical educator because a superficial approach of viewing work values as ‘giving better lectures’, ‘becoming more popular with students’, or ‘securing a job’ could lead to burnout (Participant A). Nonetheless, they believed that medical educators who possess a professional calling and an educational philosophy can ‘continuously dedicate themselves’ and bring ‘change in the field of medical education’ (Participant D). The participants agreed that, for medical educators, having an ‘educator mindset’ is more important than possessing ‘educational skills’ and the associated ‘educational philosophy’ (Participant F).

Some of the experiences identified by the participants played a significant role in shaping their values regarding medical education and their role as medical educators. Based on their experiences as students, residents and professors, the participants developed a critical perspective on medical education and the importance of teaching and learning methods, which highlighted the importance they placed on a medical education career. For example, one participant detailed the problems they faced as a student with ‘memorisation-based education’. However, after encountering new teaching methods, such as ‘project-based learning’, during an overseas training opportunity, they strengthened their resolve to improve medical education and decided that ‘I will dedicate myself to medical education instead of research’ (Participant A). Another participant was motivated towards medical education after encountering an ‘excellent teacher’ during their residency training who enhanced their interest in medical education (Participant C). Recognising the problems with memorisation-based education while teaching students, a participant observed their ‘inability to connect what they have studied with clinical problems’. This experience motivated them to explore and apply new teaching methods, eventually realising that Problem-Based Learning (PBL) should be their target approach, despite being unaware of its theory initially (Participant E).

Protean career process

The protean career process refers to an individual’s capability to demonstrate a protean career orientation constituting identity awareness, adaptability and career agency [12, 14]. Identity awareness implies having a clear sense of one’s personal identity and value and high self-awareness. These are the key meta-competencies associated with protean career orientation [31]. Adaptability is the characteristic of adjusting to a changing environment [32, 33]. Agency refers to the intentional act of making things happen through an individual’s actions [34].

Awareness

By recognising the importance of identity in career development, the participants could define their identity and role as medical educators. Consequently, their performance within the organisation improved, thereby, continuing their career development:

‘Who is a medical educator?…If this isn’t clear, people may get confused. So, while carrying out activities, the territory of medical education must be clearly defined’. (Participant G)

A participant encountered role conflict due to ‘dual positioning of the job’, however, observing senior medical educators and their dedication to work served as motivation for maintaining a medical education career (Participant D). Additionally, recognising the commonalities between clinical practice and medical education led to the discovery of similarities in the roles of a clinical physician and a medical educator, which is ‘100% the same’, facilitating the integration and development of both roles (Participant F). The identities of clinicians and medical educators were not mutually exclusive, instead developed through convergence. Furthermore, their activities showed a synergistic effect that was mutually beneficial:

‘Did the education have any influence on my clinical activities? Of course, it certainly did. I think both sides can provide synergy with each other. I think it would be better to just have fun and work hard at it. Both influence each other positively, I think’. (Participant G)

Adaptability

The participants highlighted the need for the evolution of medical education based on social needs and the medical environment. To achieve this, it is necessary to examine medical education at a ‘global level’ rather than having a ‘tunnel view’ (Participant B). Additionally, medical educators are expected to ‘always look ahead’ and ‘try to figure out future changes at least 10 years in advance’ (Participant A). A flexible and macro-level mindset is essential for medical educators due to the dynamic healthcare environment:

‘I believe that medical education has been changing depending on the medical environment and is not fixed but flexible. That is why medical educators must work with insights and a broad perspective that allows them to see the whole picture’. (Participant E)

In the Korean context, the participants encountered demands for educational changes, such as improvements in the national exam, the introduction of practical exams like OSCE (Observed Structured Clinical Examination) or CPx (Clinical Performance Exam) and the adoption of computer-based methods. When these educational changes first emerged, they ‘didn’t know what they were’ (Participant D). However, to adapt to these changes, they engaged in self-directed learning to study the ‘educational philosophies and terms’ related to new assessment methods, such as OSCE and CPx, and ‘tried to learn educational theories’ (Participant D).

Agency

Additionally, the participants acknowledged that having strategies for inducing and implementing changes proved crucial in shaping and managing career development as medical educators. They perceived that educational innovation was possible by changing the professors’ ‘mindset’:

‘I think that changing the mindset of professors is the most important thing. If the professor’s mindset changes, we will be able to build a proper system. However, if the mindset does not change, we will end up failing’. (Participant B)

They encountered resistance due to varied wills and values among faculty members while attempting to implement changes in medical education. Faculty members often resisted change because they ‘had not experienced it before’ (Participant I). In such cases, it is important to ‘explain why it is needed’, ‘communicate the reasons continuously’ and ‘prepare them well to experience success’ (Participant I). Additionally, regularly holding one-on-one or group discussions to engage faculty helped ‘facilitate their understanding of current medical education issues from educational perspectives’ and ‘foster their interest in education’ (Participant A).

Additionally, medical educators recognised the importance of communication with students for applying new curricula or teaching and learning methods. They shared the school’s policies and explained the educational agenda to students while listening to their needs:

‘We had a meeting with the student representatives once a month and talked about the school policies actively. Students discussed their needs every time and presented them to us clearly. We always held an information session for the whole student body at the beginning of every semester’. (Participant D)

Changes enacted through formal institutions by implementing accreditation processes proved effective in improving education quality to ‘share what was the national or international standard and the future direction of medical education’ (Participant F). Additionally, ‘when such changes are unlikely to occur voluntarily’, legislated accreditation standards facilitated the necessary transformations (Participant C). Thus, medical educators’ career activities, through formal institutions, proved effective in inducing changes within individual and across medical schools nationwide. Although medical educators faced significant resistance when working with formal organisations, they overcame these challenges by collaborating with the ‘core members’ and ‘working jointly to navigate the difficulties’ (Participant F).

Protean career outcomes

Protean career outcome includes subjective and objective career success and organisational commitment. Subjective career success refers to the psychological experience of success based on an individual’s goals or expectations, while objective career success refers to observable and measurable achievements [35,36,37].

Subjective career success

The participants found their role as teachers in medical education significant. As both medical educators and teachers, their greatest joy lay in meeting students and nurturing them into good physicians:

‘I think it’s the most important thing to have fun in medical education. I’m very lucky to have been involved in medical education. There is no better job than that of a medical educator in the pursuit of fostering good physicians’. (Participant F)

The participants experienced psychological satisfaction and a sense of reward by fostering student growth and learning. For example, Participant F felt satisfied when teaching students how to ‘explain medication to elderly patients’, which improved their ‘communication skills’ and positively changed ‘students’ attitudes and behaviours’. Additionally, Participant D felt immense gratification upon seeing ‘enthusiastic reactions’ from students after introducing PBL, observing that ‘students enjoyed solving problems on their own rather than simply being given knowledge’. These examples illustrate that the medical educators’ subjective career success is derived from both teaching knowledge or skills and witnessing essential changes in students, such as their attitudes and behaviours towards patients, and their enthusiasm for learning.

Objective career success

All the participants were conferred social recognition through awards for their contributions to the field of medical education and held leadership roles in relevant organisations. They successfully organised large-scale international medical education conferences for academic collaboration, with ‘participation from more than 800 medical educators from 57 countries globally’ (Participant C). Additionally, they drew on their experience in medical education within South Korea to advance medical education in other countries, advising ‘basic medical science education development’ (Participant B) or ‘clinical education improvement, portfolio development, student learning assessment, and curriculum design and evaluation’. (Participant A).

Forming networks was considered an objective career success. While developing their careers as medical educators, they formed social and academic networks to share experiences and knowledge to solve problems and induce change in medical education:

‘I thought it is necessary to create a group of people who love medical education, who are passionate and committed to medical education, to support each other by sharing theoretical background knowledge for practical application. By learning and working together in medical education, we learned about each other’s challenges and became very close’. (Participant H)

Organisational commitment

Participants emphasised the importance of organisational trust for medical educators to experience early career success, ‘the trust and encouragement from the faculty community significantly influence their career decisions as they plan their future’ (Participant I). Moreover, to sustain their careers without burnout, they recognised the significance of experiencing ‘small successes’ and emphasised the need to ‘provide opportunities for developing careers from small successes and engaging in higher-level decision-making’. (Participant D).

The career development of medical educators requires a supportive environment for medical education, along with various forms of support for faculty development, to provide learning opportunities:

‘It is necessary to create an atmosphere that supports medical education. This support may include sending for training programmes, creating a fund, or supporting educational research. Additionally, medical educators need to be given opportunities to frequently participate in medical education-related meetings and conferences’. (Participant G)