Eve, here. I have to confess that I’m not much of a game player. But Wordle is so popular that almost everyone here is familiar with it, and I’m sure a fair number of people enjoy it. Rajiv Sethi discusses group performance in Wordle, and by extension the practice of other skills, along with some findings that seem counterintuitive. One is that the most popular view tends to be correct, except in cases where it isn’t, like in a bubble.

Prominent quantitative trader Cliff Asness believes crowd correctness reflected in market prices has worsened over the past few decades, but he doesn’t seem to have a theory as to why. I have one. The business world has gotten pretty good at propaganda and advertising. I once told a story about a Wall Street Journal reporter who went to Shanghai to open an office around 1993. He returned to the United States in 1999 and was surprised to see how much business journalism had changed. First, the Internet has all but eliminated the typical publication deadline in which a daily issue must be put to bed in order to go to the print shop. As a result, news cycles have become shorter, making it nearly impossible to get to the bottom of a story before it’s published. Second, companies’ ability to spin has increased significantly, making it once again difficult to stay on top of information. As a result, the baseline of knowledge has eroded and the public is no longer able to take an informed view.

Written by Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University. External professor at Santa Fe Institute. Originally published on Imperfect Information

I hope this post has something useful to say about strategic diversity, meritocratic selection, and asset price bubbles. But before we get there, we need to take a detour to Wordle, a popular online game played by over 1 million people every day.

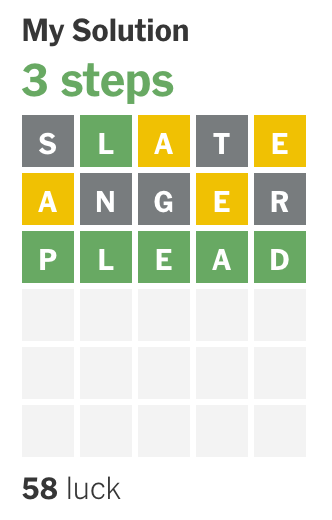

The New York Times acquired this puzzle from the developer in 2022 and added some features that generated some interesting data. Each participant can evaluate their performance against an algorithm (wordlebot) designed to minimize the expected number of steps to completion. The bot typically finds a solution in three or four steps and evaluates each player’s participation at each stage based on skill and luck. These scores range from 0 to 99, and while a few players can beat the bots every day thanks to luck, the best you can do in terms of skill is to match them.

As far as I can see, no individual player can consistently solve puzzles faster than a bot over an extended period of time. However, I argue below that bots can be defeated in almost all cases if a large, randomly selected group of players from around the world work independently and vote on solutions. I was initially surprised to see this pattern and thought it was due to widespread fraud, but the scale of the fraud is too small to explain the impact. Something more interesting is happening.

As an example, consider the set of entries selected by the bot on November 26th.

Note that the second word here is excluded by the feedback on the first word. This is a common strategy for bots. If your goal is to minimize the expected number of steps required, limiting yourself to only executable words at each stage is suboptimal.

Most human players don’t behave this way. At each stage, it tends to select words that have not yet been deleted, which produces a noticeable effect. Based on approximately 1.8 million entries, the most frequently made choices for the second stage of the November 26th puzzle were:

Note that the word selected most frequently is actually the solution. If a large, randomly selected subset of players from the participant pool submitted their choices at each stage to an aggregator, and the aggregator simply chose the most frequent word as the crowd’s choice, then on this particular day the crowd would have won over the bot.

But it’s not just this day. Based on data from the past few weeks (starting November 1st), crowds never took more steps than bots, and 85% of the time they took exactly fewer steps. The bots took an average of 3.5 steps to solve the puzzle, while the crowd took an average of 2.4 steps. More than a quarter of the time, the crowd found the solution in two steps, while the bot took four steps.

When I first noticed this pattern, I was convinced that it must be due to widespread fraud. Perhaps the player tried multiple times using a different browser or device, received hints from others, or simply looked up the solution before entering it. There is certainly some evidence of cheating. Approximately 0.4% of players find the solution on the first try. This is about twice the rate that would be expected by chance alone. However, if the amount of cheating is large, the average “luck” score of the crowd should be much larger than the average score of the bots, but this is not the case at all. For example, the average luck score for bots over the past two weeks was 54, while the average luck score for the crowd was 56. Therefore, the scale of fraud is negligible and cannot explain patterns in the data.

This is what I’m thinking.

Firstly, the choices are very diverse in the first round. The 10 most popular words together account for only 30% of the choices on a typical day, but hundreds of different words are selected in the first step.

Second, in subsequent stages, players tend to choose only feasible words. Each player is faced with a set of words that have not yet been removed from their previous choices. The diversity of choices in the early stages means that these sets vary widely in size and composition. Furthermore, all such sets must contain the actual solution, so the solution must appear most frequently in the union of these sets. Even if all players choose completely randomly from among the remaining viable words, the most likely winner in the second stage should be the actual solution.

By the third stage, I think the most popular choice is almost certainly the correct one. In fact, this is what we see in the data. Since November 1st, spectators have solved puzzles in two steps about 60% of the time, and have never required more than three steps.

This reasoning leads to an interesting hypothesis. This means that a large pool of randomly drawn participants can find a solution faster than a pool of the same size that includes only the most skilled players. The latter pool has little strategic diversity, with all players operating in a very similar way to bots. This hypothesis can be tested experimentally. If verified, it would provide significant evidence for Scott Page’s claim that there are conditions under which cognitive diversity trumps ability. This, in turn, has implications for how merit is conceptualized as a characteristic of teams rather than individuals.

Wordle’s audience success is similar to that of the TV quiz show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Contestants stuck with a question can choose to poll the audience, with each member independently submitting their best guess out of four possible answers. The success rate for the most popular answers is very high, reaching 95% for questions of low to medium difficulty.

In a recent conversation with Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway, Cliff Asnes explained why this lifeline tends to be successful:

At least in my non-exhaustive testing, it seemed to work almost every time, even when the questions were difficult. Imagine 100 people in a room. 10 of them know the answer. Others are guessing. The 90 is evenly distributed among the four. It may not be perfectly even, but it’s almost even. All 10 pieces land on B. That is, B is larger, so we choose B. It worked pretty well each time.

It has an important premise. Audiences should be relatively independent of each other. And they did it. they weren’t talking. It was a silent vote. If everyone in the audience could speak, 10 people might be able to persuade 90 people, but that might not be the case. Perhaps a demagogue with a better Twitter feed will convince everyone. And if you mess with independence… have we ever come up with a better means than social media to turn the wisdom of the crowd into the madness of the mob? It would be difficult to explain it.

Independence of choice here is very important. If a contestant thinks out loud before activating a lifeline, it can induce response correlation and impair accuracy. One of the reasons the Wordle crowd is so successful is that it is made up of millions of people spread around the world, most of whom work independently.

Cliff Asness was a student of Eugene Fama at the University of Chicago, but he is not a dogmatic supporter of the efficient market hypothesis. In fact, he seems to think the market has become less efficient over the past few decades, claiming that it “went from 75-25 Gene (Pharma) to 75-25 Bob (Shiller).” He, like many others, is concerned that we may be living in an AI bubble.

What maintains asset market bubbles is the difficulty in timing a crash. Even if some assets are widely believed to be overvalued, those who bet on a decline may do so too soon and be forced to liquidate their positions before profits begin. This was the fate of many short sellers in 1999 and early 2000, before the tech stock bubble finally burst. The problem is one of coordination. Betting on falling prices is very risky and is likely to fail if done alone. Eventually adjustments will be made, but if you act too soon you may lose your shirt.

We may or may not be in the midst of an asset price bubble, but it would be naive in the extreme to dismiss Cassandras’ argument on logical grounds, as people sometimes do. When the stakes are small, such as in quiz shows or online games, the crowd may be wise, but when the stakes cannot be large, they are susceptible to abnormal public delusions. This may seem paradoxical at first glance, but it makes perfect sense if you think about incentives with enough seriousness and care.