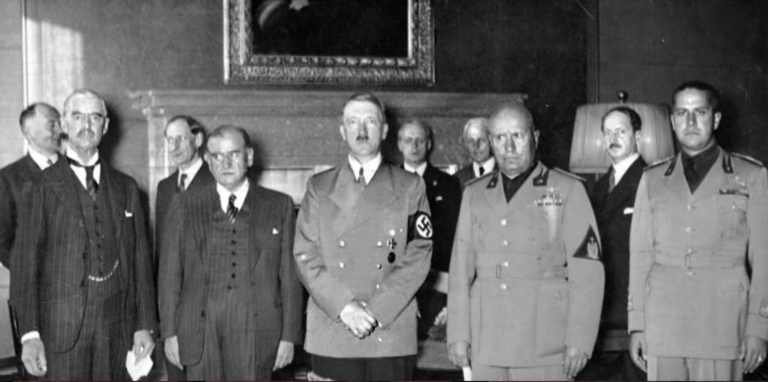

In September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain signed a pact with Adolf Hitler. Britain (and France) would allow Germany to occupy parts of Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland) inhabited by ethnic Germans in exchange for a promise not to make further inroads into Czechoslovakia. Upon his return, he declared that he had guaranteed “peace in our time.” A few months later, Hitler took control of all of Czechoslovakia.

In my book entitled The Midas Paradox, I cited a NYT report on market reaction to the Munich Agreement.

“From a strictly market point of view, the news of the Czech government’s decision to cede the Sudetenland to Germany was positive. Naturally, as the threat of war appeared to have receded, Prices have improved. But this was “good news” with a difference. It’s hardly the kind of good news that captures the imagination and evokes the bullish spirit of individual traders. Even on Wall Street, where pragmatic mental processes are supposed to be very intense, the tragedy that accompanied the capitulation of Czechoslovakia and the unfortunate role that Britain and France played in it were felt with sufficient intensity to dampen the usual speculative impulses. was. ” (New York Times, September 22, 38, p. 33)

This happened a long time ago, and I suspect that few Americans now understand the consequences of appeasing a tyrant who promises he only wants a piece of his neighbor.

I was reminded of this market reaction when I read the following tweet: