Eve is here. Even if we do not necessarily agree that the findings of these authors can be adequately generalized beyond the cases they studied, we cannot immediately dismiss their conclusions. For example, it was found that countries that lost a war suffered a major setback in terms of democracy. Our accelerating slide toward authoritarianism is consistent with their findings, since the United States has almost always lost wars since World War II, with the exception of questionable success in the Iraq War (and we fail to acknowledge that it was more a Russian victory than ours).

But what about the collapse of democracy in the EU? Among other things, largely unelected bureaucrats have taken control, with increasing censorship, canceling elections and banning candidates, with shocking examples including Jacques Bo. Perhaps it falls into the category of “first war”. The Kosovo bombing occurred before NATO expansion, and the only ground forces involved were peacekeepers, so it was probably not a war in the conventional sense, much less a war waged by current EU/NATO members.

Written by Ephraim Benmelek, Henry Block Professor of Finance and Real Estate and Director of Northwestern University’s Crown Family Israel Innovation Center and Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research, and João Monteiro, Assistant Professor at the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance. Originally published on VoxEU

The war doesn’t end even if the fighting stops. This column uses data from 115 conflicts and 145 countries over the past 75 years to show that war causes large-scale and sustained declines in democratic institutions. However, this decline is not inevitable. It emerges only in specific situations, such as first-time conflicts, domestic wars, and disputes won by the government, precisely where the executive faces the strongest incentives to extend its authority. The evidence points to a political mechanism. War does not require dictatorship, but it creates opportunities for leaders to weaken constraints, suppress opposition, and consolidate power in ways that are difficult to justify in peacetime.

Do wars strengthen or weaken democratic institutions? Classical accounts point in the opposite direction. For example, Tilly (1992) argues that in 17th and 18th century England, repeated interprovincial wars forced the states to raise taxes and negotiate with parliament, increasing the power of parliament and tightening constraints on the executive. In contrast, Tocqueville (2011) argues that in revolutionary France, a combination of intrastate conflict (revolution) and a series of interstate wars led to a significant expansion of executive power. More recently, Becker et al. (2025) provide evidence on the impact of conflict on the development of democratic institutions in Europe. (2019) show that political violence shapes local fiscal institutions in Colombia.

Which of these paths is preferred is ultimately an empirical question. A new paper (Benmelech and Monteiro 2026) provides the first systematic global evidence on when, where, and why conflict erodes democratic institutions. We do this by leveraging the dataset built for a previous paper by Benmelech and Monteiro (2025). This dataset includes 115 conflicts and 145 countries from the past 75 years, including both interstate (state vs. state) and intrastate (state vs. non-state) wars.

Global Perspective: Democracy at War

Our analysis combines comprehensive conflict data from the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset 1 with high-resolution institutional measures from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project. We track how democratic institutions evolve before and after the outbreak of conflict, comparing countries that participate in war (treated countries) with similar countries that are otherwise free of conflict (control countries). Our main measure is the V-Dem Democracy Index, which captures multiple dimensions of the quality of democratic institutions.

Two facts are immediately obvious. First, countries do not go to war just because their democracy is in decline. In the years before conflict begins, democratic institutions in treated countries are stable or even slightly improved compared to control countries. Second, autocracies are less likely to be involved in conflict than democracies in the same region.

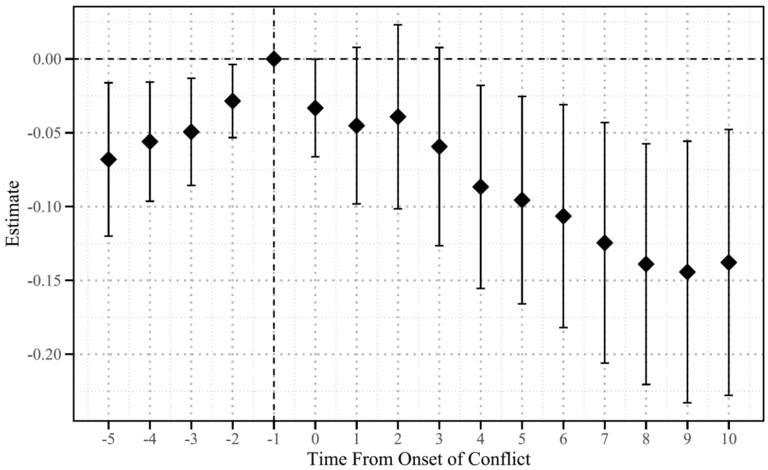

Conflict causes a significant and sustained decline in the quality of democratic institutions, as measured by the composite democracy index. As shown in Figure 1, conflict initiation is associated with a 3% decline in democracy. Even more striking is that the decline has lasted nearly a decade, even though the median duration of conflict is only three years. Ten years after the outbreak of the conflict, democracy in treated countries is about 13% lower than in managed countries. This is a big decrease. The estimated 10-year change is at the 14th percentile of the global distribution of 10-year change. This means that 86% of all observed changes in democracy around the world are less negative than our estimated effects.

Figure 1 Impact of conflict on democracy index

Democratic decline unfolds through a coherent set of political channels. Conflict leads to a large-scale and sustained increase in media censorship and judicial purges, directly weakening constraints on executive power. Core civil liberties will also be eroded, freedom of association will decline, and governments will become even more dependent on the military as a base of political support. These changes are accompanied by increased political instability. Treated countries are more likely to experience extrajudicial leadership changes, such as coups, forced resignations, or assassinations, and the suspension of constitutional rules.

Taken together, these patterns indicate a common mechanism. The institutional changes brought about by conflict are political rather than functional, weakening opposition, loosening checks on the executive, and expanding coercive powers, but do not reflect the operational requirements of fighting wars. Rather, conflicts create opportunities for incumbent powers to reshape institutions in ways that are difficult to justify in peacetime, and whose effects linger long after the fighting has ended.

Not all wars erode democracy

Democratic setbacks are not universal. It is concentrated in a very specific political and institutional environment.

First, democratic erosion occurs almost in the first conflict. Countries that have been to war before experience little additional institutional damage. In contrast, first-time conflicts lead to significant and sustained declines in the quality of democratic institutions. When democratic checks are weakened, there is little left to erode.

Second, setbacks are caused by conflicts within states, not wars between states. Civil wars and internal conflicts cause governments to face internal challenges and lead to rapid institutional deterioration. Foreign wars are not like that. Moreover, democratic decline associated with outbreaks of intrastate conflict is concentrated in highly fragmented societies, where internal divisions increase the return to political repression.

Finally, and most surprisingly, only countries that win wars experience democratic backsliding. Losers don’t. As Figure 2 shows, 10 years after the conflict began, the quality of democratic institutions in the victorious states has declined by nearly 40% compared to the control group.

Figure 2 Winners and losers

War does not reward tyranny.

A natural interpretation is that the erosion of democracy reflects the functional demands of war. Perhaps a centralized authority is simply more effective in combat. This view is consistent with the findings in Figure 2. Perhaps countries win wars because they become more authoritarian.

The data refute this explanation. We show that countries that become authoritarian during conflicts have no chance of winning the war. Rather, institutional instability reduces the likelihood of victory. Therefore, we find no evidence that democratic decline is a functional requirement for war.

War as a political opportunity

Rather, the evidence supports a political interpretation. Conflicts reshape domestic politics by weakening opposition, expanding coercive power, and legitimizing extraordinary measures. None of these phenomena are functional requirements for war. Furthermore, there is little evidence to support the hypothesis that these changes in organizational quality increase the likelihood of victory. Victory further strengthens the incumbent power and allows it to carry out institutional reforms that would have been difficult or impossible in peacetime.

This helps reconcile competing views in the literature. War can increase state capacity, but it can also undermine democracy. Whether or not to do so depends on political motivation, not military necessity.

Recent research (Acemoglu et al. 2025) emphasizes that well-functioning democratic institutions are self-reinforcing. Our results show a darker correspondence. When war weakens these institutions, the damage can last for decades.

what it means

The lesson is not that war necessarily destroys democracy. Rather, democratic resilience depends on political constraints rather than the absence of conflict itself. First wars, domestic wars, and victories are precisely the moments when these constraints are at their weakest.

As armed conflicts become more frequent around the world, understanding how to prevent war from becoming a gateway to autocracy is not just a political concern, but is critical to the long-term health of democracies and economic systems.

See original post for reference