Eve here. This post provides many important observations from the forefront of efforts to protect endangered species, but oddly skips the major issue of habitat loss as humans seem to be in demand for more calories and income. So, considering that it means human retreat, a viable coexistence, an option I have not yet seriously discussed.

Let’s consider the United States. Many have a well-known video on how the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone has led to major changes in ecosystems, including rivers and stream paths. However, wolves have a large hunting range. They can “reintroduce” more if it doesn’t. A particular visible change in suburban America is the corresponding increase in the coyote population that wolves eat. An increase in the number of coyotes will thin out the fox, which will save grey foxes grab their bait and close the trees (not so successful).

Ashraf Shaikh, Wildlife Biologist and India-based conservation research. His work focuses on the interaction of human life in the central Indian landscape, with an emphasis on conflict resolution, community engagement and socioecological dynamics of shared spaces. Originally published on Undark

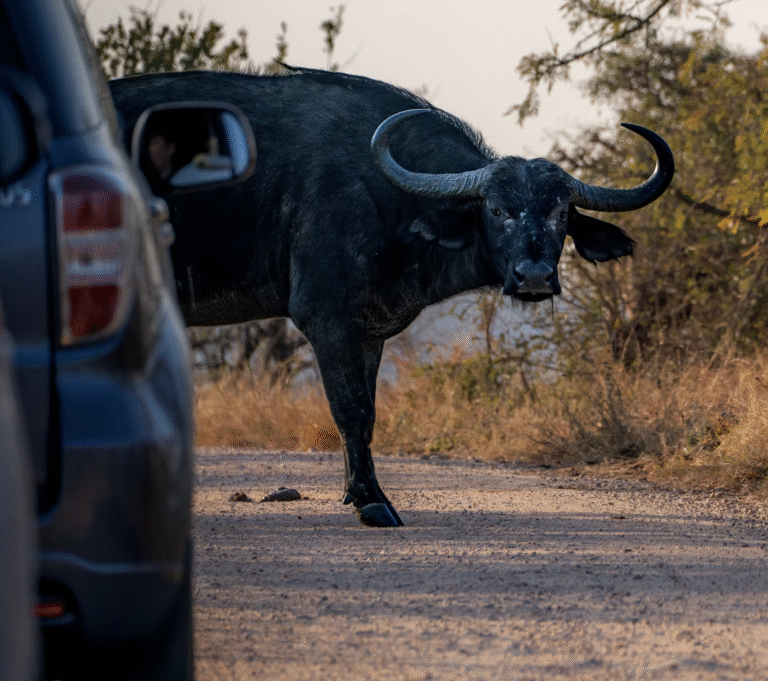

In the second half of the 20th century, the Ter conflict domesticated the nalativo and scientific literature of the Bush Conservation on the interactions of human life. Stories of elephants matching fields, leopards in front of livestock, and tigers attacking people have frequently appeared in Indian media and scientific reports. The Asee Encounts were surrounded by wildlife as dangerous intruders, humans as helpless victims, or as potential hostile invaders. The policy was driven by fear, protectionism and removal and followed suit.

By the early 2000s, a quiet revolution in language had begun. Conservatorists, scholars, and practitioners have increasingly started to see the interactions of human life through coexistence, a more gentle and hopeful framework. It challenged the Tirad Binary of conflict and harmony and embraced the complexity of shared spaces. The idea was to move beyond the simple victim and perpetratra model, instead focusing on how humans and wildlife learn to live with their respective Ohers.

At its best, coexistence provided a radically compassionate lens. It highly value mutual resilience and a rich knowledge system that informs people of the emotional and cultural ties and positive interactions they form with wildlife. They asked us to imagine the world, not fortresses or fears, but governments made up of mutual accommodation.

However, as Terg gained popularity, its elasticity was rescinded. Coexistence appears to have been transformed into a kind of generic justification that was deployed by governments, deployed by governments to slow action, and deployed by researchers who disinfect fieldwork, and by non-governmental organizations to maintain reputable capital. That misuse now does not function much as an ethical compass, and acts as a Riolical shield. Conceit is becoming painfully clear. Human suffering has been culturally overhauled, and wildlife is criminalised and false.

Consider how I have worked in Chandrapur, an eastern Maharashtra district, for the past few years as a wildlife biologist and conservation research. Between Tiger Reerves and fragmented exhibits, Chandrapur is one of India’s most populous tiger landscapes outside the officially protected zone. Here, tiger attacks are not an unusual event. They are so routine that they get in the way.

From 2013 to 2023, 300 people were attacked by the district’s Tigers, killing nearly 150 people, according to forest department records. My research shows that most of these attacks are not within Forres. They are south subsidence of the agricultural sector, or early morning ambush when people go out to the flaws. Often, the victim is an elderly man, who does everyday household chores that require challenging the periphery of forest areas or caring for their own fields.

Our teams repeatedly flag the need for responsive systems, including adaptive risk communication, strategic fencing, early warning mechanisms, and emergency response teams. But what we encounter more frequently than policy is the deployment. In meetings and informal discussions with forest staff and local researchers, a single phrase is repeated like a babysitter. “The people here are used to it.”

The phrase is seemingly conscientious and cold. It reported how to tolerate weapons and reconstruct tragedy as resilience, and how to turn cultural norms into repeated trauma. It absolutely silences the voices of those who live in fear of a state of responsibility. It reduces death to data and greef shruggs.

But coexistence here doesn’t mean jus will make people fail. The Tigers have also failed. The big cat involved in a fatal encounter becomes barren and is held captive for the rest of his life. Others are moved to the forest where they have Dae Nuung, where they become confused and wander back into human settlements. Sub will be killed. Ironically, various tasks are intended to protect tigers.

In Chandrapur, Coexistence has stopped becoming a shared ethic. It has a scholarship to the Mirage, suggesting harmony where there is an imbalance, and making choices where there is a forced approach.

Moving east, Sundarban, the world’s largest mangrove forest, spans India and Bangladesh. Here, water, forests and predators form a complex web of life. Tiger swims through the channel. Humans challenge the path for fishing, honey and fire. The danger is ubiquitous, but so is devotion.

The cultural story is fixed in the worship of the Bombbibi region, the forest goddess who was respected to provide protection from tigers. Before entering the forest, honey collectors and fishermen offer prayers, flowers, chants and whispers hopes in her schnes. This spiritual framework promotes psychological resilience that helps people navigate risks.

However, it is also conveniently co-employed by states and conservation organizations. The officials and NGO offers introduce the cultural ties of the community with the Tigers as reasons to explain inadequate infrastructure, poor compensation for Thue Feed, and lack of precautions. If Subeone dies in a Tiger Attack, these families may not be able to gain support if Partilly and others deem the forest invasion to be fraudulent.

Loss isn’t just emotional. The widow of the victim is often accused of Swami Kejos, literally “husband eating” in Bengali and faces social exclusion. Many are further boosted by the economic instability of finding jobs and remarriage.

Again, wildlife isn’t that good. Problem tigers are rarely addressed through aggressive measures. They are prognosed only after multiple incidents, and Offie has lost Eisher’s relocation or fatal control. Coexistence here becomes a mask, justifying national indifference, facilitating community suffering, and replacing institutional support with the endurance of cultural treatment.

Sundarban is located not only to tigers with unique characteristics, but also to bring together the communities that are hit by South Asia’s most marginalized climate. Respect is not a relief. Culture is not compensation.

This story distortion is not the case for South Asia. A similar dynamic took place in Zimbabwe’s Hawange National Park.

Hwange has an estimated 45,000 elephants, about three times the ecological capacity of the region. Drugs and rare resources push the herd out of the park from outside to nearby villages.

In response, authorities and NGOs are turning their eyes to technology. Last year, Zimbabwe Parks and the Wildlife Control Agency worked with the International Animal Welfare Fund to deploy the Earth Ranger A GPS tracking system that sends real-time alerts when collared elephants approach human settlements. Local “Community Guardians” will regain their early warnings and be delivered to households either by posting to WhatsApp groups or via bicycle messenger.

However, 16 elephants were collared in small fractions that limited the range of the system. Beyond this technique, villagers continue to rely on rattles, chili fences (splits of strings infused with chili oil), and guards. On the other hand, compensation is weak or remains unchanged. Funeral support is usually only small and human deaths continue to provide minimal relief.

Nevertheless, coexistence remains prominent in conservation messages. The workshops still preach patience, and NGOs promote tolerance even when farmland is lost and communities are associated with scarce support. Meanwhile, in the first quarter of 2025 alone, 158 animals involved in the conflict were culled after 18 people died.

In Hange, like Chandrapur and Sundarban, you embrace too many scholars and have a comforting distraction that allows Instad to showcase moral attempts, not strategies, but material responsibility to humans and wildlife.

When interventions are delayed in the name of tolerance, wildlife begins to adapt in problematic ways. Predators are bolder and have fear of human space. It develops Habats that abuse raid crops and risk rewards. Over time, these behaviors increase the frequency and severity of competition.

One common response is the translocation placed in the rest of the animals in the conflict zone, a safer area. But this often fails. Leopards are released into forests far away from the capture site. The elephants moved to Sri Lanka, and northeastern India was hungry, reached or failed to integrate into existing herds.

These mistakes reveal painful truths. Wildlife is not part of the landscape. It is part of the ecosystem of shapes and subformal narratives damaged by human sheep. Animals are not passive icons of nature. They are more enthusiastic participants, and who changes with all missteps and delayed interventions.

The theme is abandoning coexistence because another ideal has failed. But doing so was a mistake. The problem is not by concepts, but by means of it. There still exists a more grouted, ethical form of coexistence. But it’s not romantic and has to be reclaimed.

The model of coexistence justice generates and defines acceptable risk thresholds for people and wildlife. Tolerance is not innate, but must be acknowledged that this trust, equity and dialogue has been constructed. Speech and fair compensation and mental health support need to be reestablished after a conflict case. Finally, in the subject landscape, coexistence may seriously require ecological or social reconstruction, and access to treating coexistence not as a badge of cultural resilience, but as a sharing, negotiating, and constantly evolving agreement.

I need Community Don poetry. They need a policy. Wildlife does not require abstraction. Security is required.

If conservation is to maintain its ethical integrity, we must stop using coexistence as a moral curtain that hides behind. True Coexistence is not a slogan to print on a poster, nor is it a checkbox for fundraising proposals. It is a non-regulatory negotiation that calls for living room, breathing, humility, responsiveness, shared responsibility. It does not avoid it, it means interacting with complexity. It means acknowledging that people are tired of being tolerant. And even that submarine, even wildlife, pays the ultimate price for our institutional indifference.

Coexistence can still be a powerful ideal, but only if you use it to mask harm and then start using it to repair trust. We stop hiding behind words and begin to show up in our actions.