Conor here: The following article highlights a growing problem, but I’m not sure that expanding the Refugee Convention to cover people displaced by environmental factors is the panacea the author hopes it will be. Laura Robson, a history professor at Pennsylvania State University, wrote a book about how treaties of displacement and other statuses have always been designed to serve the interests of capital, not refugees (Human Capital: A History of Putting Refugees to Work, 2023).

The Refugee Convention has been in turmoil since the United Nations Relief and Works Agency’s idea to exclude Palestinians from the “universal” treaty and allow the U.S.-led international community to create different categories of refugees based on their place of origin and mode of migration. Since the 1980s, there has been a wave of new labels surrounding the concept of “temporary protection,” which turns refugees into guest workers with few claims to rights.

Displaced persons who are still recognized as refugees under the Convention typically have to pay for their designation and associated assistance, involve physical confinement (sometimes in special economic zones), and submit to biometric identity management systems and data mining.

Therefore, many people like to say that we are not prepared for what is coming. It’s probably more unfortunate than that. Certain institutions are ready. They only aim to exploit, not help.

By Rachel Mellor, writer for Better World Info, a nonprofit platform focused on global issues such as peace, human rights, the environment, and social justice. Cross submitted by Common Dreams.

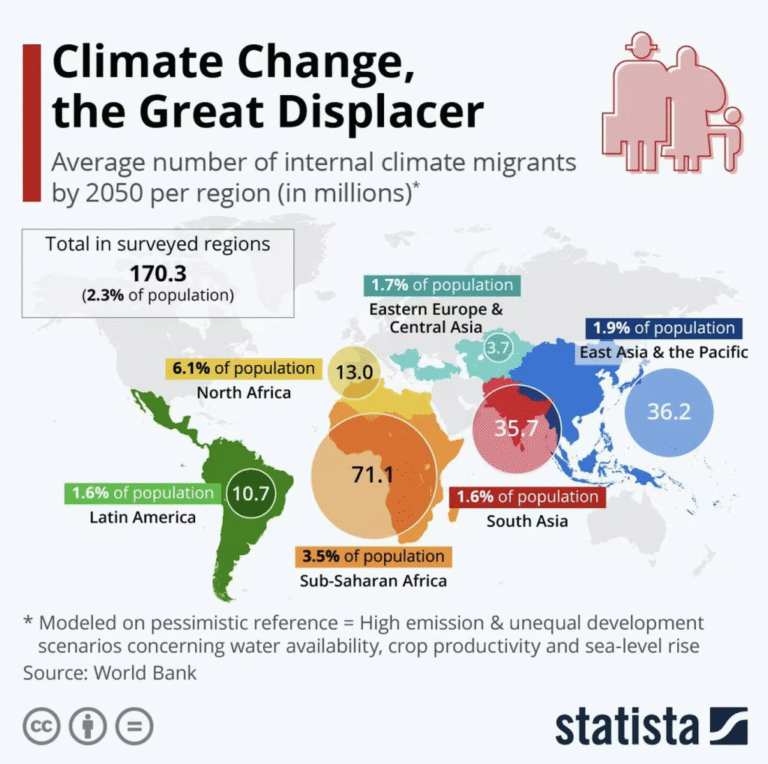

The effects of global climate change extend far beyond rising temperatures, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events. Human displacement due to the climate crisis is now one of the world’s most pressing issues, with predictions that there could be more than 1 billion climate refugees by 2050.

The plight of these people is ignored and forgotten, as they remain unprotected by law and excluded from international aid programs.

Climate refugees are forced to flee their homelands due to environmental degradation and the occurrence of climate-related disasters. Climate change is now one of the main causes of large-scale forced displacement.

Climate change is also increasing rates of poverty, insecurity and violence, further driving migration.

Those on the front lines of climate change are often in the countries contributing the least to climate change. Much of the climate change is domestic, placing unsustainable strains on these countries’ already limited resources.

“When people are forced out because their local environment has become uninhabitable, it may seem a natural process and inevitable…However, climate degradation is often the result of poor choices, sabotage, selfishness and neglect,” Pope Francis said.

humanitarian crisis

In 2022, climate-related disasters accounted for more than half of newly reported displacements. Almost 60% of existing refugees and internally displaced persons live in countries that are among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Demand for humanitarian assistance due to climate-related disasters is predicted to double by 2050. In 2023, the countries with the highest number of new internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to environmental disasters were China, Turkiye, the Philippines, Somalia and Bangladesh. Three out of four refugees and displaced persons are in countries experiencing both conflict and high risks from climate change. By 2030, 700 million people could be displaced due to water shortages. Up to 75% of Bangladesh is below sea level. Rising water levels have already affected 25.9 million people. Unpredictable rainfall patterns, desertification, and declining agricultural productivity are eroding rural livelihoods and forcing migration to urban areas. Climate change perpetuates poverty. The World Bank estimates that without urgent action, an additional 32 million to 132 million people could fall into extreme poverty by 2030. Climate change is not just an issue for developing countries. In 2022, 3.2 million people in the United States will be evacuated or displaced by wildfires, floods, and hurricanes. Between 1.6 million and 5.3 million people are expected to be displaced in Europe by the end of the century due to rising sea levels.

Expanding legal protection

(Photo courtesy of Ramazan B/CC BY 3.0)

Climate migrants remain in an ambiguous legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

The Refugee Convention, which entered into force in 1954, was established to protect people fleeing persecution from the atrocities of World War II. That protection applies only to people who have to leave their home country because of war, violence, conflict, or other types of abuse. Also, people who are displaced in their own countries are not protected.

Because the vast majority of climate refugees have not crossed borders or fled violence, their status falls outside the scope of the Convention. These facts do not mean that these people are less in need of assistance or that their lives are not equally at risk, but the law ignores their plight.

Refugee advocacy groups have called for the treaty to be expanded to include the rights of people displaced by environmental factors, but they have encountered significant political opposition. Critics say it will weaken protections for severely persecuted people. A further barrier is the difficulty in proving the causes of climate change.

The 1998 Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons help bridge the gap in climate refugee protection. However, since it is not binding, its practical effect is limited and it is not legally enforceable. Nor does it protect people who have to cross borders.

The Global Compact for Migration was adopted in 2018. This is the first United Nations framework on international migration. For the first time, climate change has been officially recognized as a driver of migration, but climate change refugees still have no legal protection. Instead, the agreement promotes safe and orderly routes for migrants, including planned migration, visa options and humanitarian shelters.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a process and a treaty to help countries mitigate the causes and consequences of the climate crisis. In 1992, 154 countries signed it. Climate migrants are not explicitly protected by the UNFCCC.

As it stands, while some countries have enacted domestic legislation to provide temporary protection for climate refugees, their lack of recognition under the Refugee Convention means that there is still no internationally binding mechanism for them.

Countries are reluctant to sign further agreements, especially since they could impose liability on climate migrants arriving at their borders and encourage more migrants to preferential countries. There are many political obstacles that ultimately exacerbate the humanitarian needs of millions of people.

We must begin to address climate-induced internal displacement in the most vulnerable countries. There is an urgent need to address the root of this problem, and to make countries historically responsible for the damage pay the price.

Climate change is a form of adaptation. New routes for safe and regular migration can be built.

The Loss and Damage Fund was established at COP27 in 2022 to address the financial needs of communities severely affected by climate change. This funding supports rehabilitation, recovery, and human mobility. Although an impressive initiative, by late 2025 rich countries will have contributed less than half of what they originally contributed to the fund.

Climate justice is immigration justice

The climate justice movement recognizes that climate change disproportionately impacts marginalized and vulnerable communities. It demands that the Global North, which bears significant historical responsibilities, bear the burden of solutions. This movement brings social justice, racial justice, human rights, and economic equality into the climate change conversation.

In July 2025, years of work by an intrepid group of University of the South Pacific law students came to fruition. The Vanuatu ICJ Initiative led legal action and led to a historic advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The following was unanimously adopted by all 15 judges: States have a legal obligation to combat global crises.

For the first time, the ICJ officially classified the climate crisis as an “urgent and existential threat” and stressed that “cooperation is not a matter of national choice, but an urgent necessity and a legal obligation.” The ICJ opinion can now be used to call for more ambitious climate protection measures, to ensure compliance with the Paris Agreement, to enforce national and international climate laws, and potentially to help protect climate migrants.

The initiative also highlighted the vulnerability of small island states and demonstrated that collective action and legal responsibility are essential tools on the path to justice and sustainable development.

Any justice for climate-induced migrants must focus on human rights. Humanitarian visas, temporary protection, residence permits, and bilateral free movement agreements could all help alleviate the suffering of those displaced.

no longer visible

“When we, refugees, are excluded, our voices are silenced, our experiences are ignored, and the reality of the climate situation in the Global South is obscured,” says Ugandan climate justice activist Aibale Dennis.

For many years, climate migrants remained under the radar in the climate and migration debate. The International Organization for Migration has worked hard to shine a spotlight on climate and environmental factors. They are establishing a body of evidence that conclusively proves that climate change affects human migration both directly and indirectly.

The United Nations Refugee Agency insists on the responsibility and obligation of countries to address the migration crisis caused by climate change. They see climate change as a threat multiplier and are working towards a protection framework.

The debate over establishing climate refugee status is ongoing, and while a legal definition would help, it would only be a partial solution. The majority of climate migrants do not want to leave their homes, livelihoods, and communities. Yes, this will not be easy, but we must address the root of the problem: climate change itself.

Without urgent action, we are all at risk of becoming climate refugees.

While addressing immediate needs, the climate change debate should continue to focus on preventive measures. Climate change mitigation, adaptation and a just energy transition are essential.

Countries must start working together on this global issue and ensure fair treatment of all refugees. We must demand a new comprehensive legal framework for climate refugees to protect the vulnerable and protect those who may be at risk in the future.

It is our moral obligation to support climate refugees.