We’re really overdue for an overview of how private debt-backed AI data center deals work and why it’s not a good sign for a company like Meta, which can borrow entirely in its own name, to not pay an additional 200-300% basis points. But the Wall Street Journal just published a very detailed article outlining this debt glut, and it’s also gaining attention in the general press as borrowing levels have skyrocketed this year.

Big Tech Borrowing for AI Data Centers:

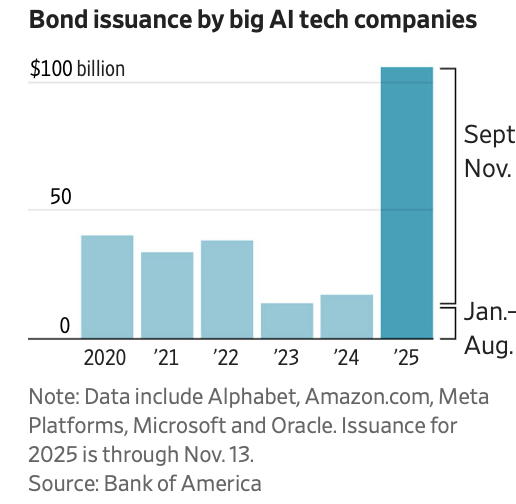

Average from 2015 to 2024: $32 billion per year

$75 billion from September to October 2025 alone

> Goal borrowed $30 billion

> Oracle borrows $18 billion

> $GOAL Blue Owl also took $27 billion off balance sheet

AI companies now account for 14% of the IG index

What is a technology company that “prints money”? pic.twitter.com/IuhBU0LS4M

— Junk Bond Investor (@junkbondinvest) November 5, 2025

And from a new article in the Wall Street Journal:

What this paper calls Wall Street’s ‘frenzy’ supercharges AI past bubble concerns The spending frenzy is starkly reminiscent of the pernicious phase of the subprime lending binge, when its founders, like the rioters of the day, financed mirror-clouding borrowers when they wanted the goods. It was not until several years later that we were able to piece together how leverage-on-leverage created the “liquidity wall” that was well publicized at the time, drawing on key factors including several insiders, as well as notable pre-crisis analysis by stock market analyst Henry Maxey of LaFleur Investments (among others). It was also the leverage (and the high exposure of systemically important but vulnerable financial institutions) that made the bubble’s unwinding so devastating. We have warned that the unwinding of traditional credit bubbles, even if very large, as opposed to the near or actual collapse of the banking system (see Japan and the S&L crisis for a smaller but still troubling version), usually causes, at worst, a very deep and prolonged recession and zombification (even in the run-up to the 1929 US crash, CDOs on leverage (For more information, see Frank Partnoy’s Match King.)

Again, we have yet to find any evidence that a meteorite event hitting the financial system is on the horizon.

However, lack of evidence is not evidence of absence.

And although financial historians may correct me, I cannot remember any historical example of a large-scale stock bubble (without 1929-style heavy borrowing directly against the stock) with so many red flags in the underlying commercial activity, especially operating and financial leverage. This included repeated transactions between major companies and, as I will discuss in this article and a few in future posts, overly clever borrowing structures that only made sense for achieving higher levels of leverage than could be achieved through traditional means. Incidentally, the Journal points out that one of the huge deals will pay more than 2% more than the plainer vanilla product. Paul Kedrowski, in his excellent June overview of how these financings work, similarly said the premium was 200 to 300 basis points. This comes at a very high cost in terms of opacity and assumed balance sheet remoteness. 1

For a quick introduction to the causes of concern about the data center boom, see the Center for Public Enterprise’s Bubble or Nothing overview (with thanks to Matt Stoller).

● Cash flow uncertainty continues as the cost of providing AI inference services continues to rise. The major AI inference service providers are not particularly differentiated from each other. This competitive market structure restrains the market

Participants have less pricing power and are unable to recover increased costs.

● The collateral value of graphics processing units (GPUs), a key asset in this sector, appears to be on the decline in the short term. Chip values fluctuate not only due to uncertain user demand, but also due to supply trends and technical specifications of new GPUs released each year. The cash flows that GPU collateral can claim are constrained by the sector’s competitive market structure and the uncertainty of existing GPU depreciation schedules.

● Data center tenants are subject to multiple cycles of intensive and increasingly expensive capital investments within a single lease term, creating significant tenant termination risk for data center developers. This asset-liability mismatch between data center developers and their tenants can strain the developer’s creditworthiness without guarantees from market-leading technology companies.

● Circular financing, or “roundabouts,” between so-called hyperscalers’ tenants (large technology companies and AI service providers) create interlocking liability structures across sectors. These tenants account for a surprisingly large share.

They are entering the market and funding each other’s expansion, creating concentration risk for lenders and shareholders.

● Debt is playing an increasing role in data center financing. While debt is a routine aspect of project financing, and hyperscalar tech companies appear able to self-fund their growth through equity and cash, the lack of transparency in some recent debt financing transactions and the sector’s linked debt structure is cause for concern.

The first two points alone, the fact that inference costs are not only not decreasing but are still rising, and a short-term drop in GPU prices should be fatal, or at least detrimental to debt financing.

But as you can see, it’s not as serious as the list above, even though the Journal raises concerns and even adds to this list by explaining how AI “hyperscalers” are placing duplicate orders on data center capacity. But it also includes signs that some dogs are turning up their nose at dog food.

Typically, stock prices rise when companies report record earnings, but after Meta did just that on Oct. 29, the company’s stock price instead plummeted 11%. Why: Mr. Zuckerberg said he would “aggressively” increase capital spending on AI, prompting questions from analysts about how the company actually plans to profit from the new technology.

What the Journal describes is similar to the late-stage subprime lending craze. In 2007, Chuck Prince, CEO of Citigroup, which later received a major bailout, famously said:

When the music stops, things get complicated from a fluidity standpoint. “But as long as the music is playing, we must get up and dance. We are still dancing…The depth of the liquidity pool is much greater than before, so disruptive events need to be much more destructive than before.

From the journal, uh, consider the lender’s enthusiasm and fear of being the wallflower of this party.

Big Silicon Valley companies were deep-pocketed and were able to finance many of the early AI builds from their own coffers. As the value of the dollar rises more and more, we turn to debt and private equity, which spreads risk and potential returns more widely across the economy.

Some of the funding comes from run-of-the-mill corporate bond sales, but financiers earn far larger fees from huge private placement deals. Virtually every player on Wall Street is getting in on the action, from banks like JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley to traditional asset managers like BlackRock.

Investor appetite for data center debt is so strong that some asset management companies are posting billions of dollars in profits within days, even before construction of the facilities they finance is complete.

Still, long-term performance is hardly guaranteed. Big tech companies are expected to spend nearly $3 trillion on AI by 2028, but will only generate enough cash to cover half of that, according to Morgan Stanley analysts.

Financial heavyweights such as Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon have warned of AI-powered bubbles in markets and capital investment.

At the same time, the fear of missing out becomes real. Days after Mr. Solomon raised his concerns with analysts, Goldman created a new team in its banking and markets group focused on AI infrastructure lending.

From the diary afterwards:

Funds investing in AI deals argue there is little risk because deep-pocketed tech companies have ironclad leases that generate money to repay investors. Microsoft has a higher credit rating than the U.S. government, and on October 29 it announced to investors that it would double its total data center footprint over the next two years.

Maybe I’m too old, but I remember that IBM and GE also used to have AAA ratings, and by 2000 (for IBM) and 2010 (for GE), their luster had changed considerably. And remember the pre-crisis pattern in which house prices never fell nationally, only regionally? These purported blue-chip technology companies are making big bets on AI, so unless they back out when the fundamental performance of their large-scale language models falls far short of promise, their historical solidity isn’t as German as it seems. Meta shareholders’ reaction to Zuckerberg’s promise of even larger AI investments is to ratify.

Return to diary:

Technology company executives believe there is more risk in under-building than over-building…

However, some technology companies are more financially vulnerable than others. Oracle…will need to borrow billions more to increase spending, and Moody’s Ratings and S&P Global Ratings are close to reclassifying Oracle’s bonds as junk bonds. The company’s stock price has fallen 32% in recent weeks, and its bonds have fallen about 7%.

There’s also the risk that the chips tech companies are borrowing to buy could become obsolete in a few years…

The last time Wall Street went all in on the industry was during the fracking boom (then bust) more than a decade ago. This time, financiers are raising even more money.

The article goes on to provide a breathtaking explanation of the boomtown effect that these data center expansions are creating. Matt Stoller has sounded the alarm on concerns about the real economy’s increasing dependence on huge spending in what should be niche areas.

A few months ago, I asked why our economy felt so ominous and unstable, even though official statistics showed steady growth. My conclusion was that the United States was stuck in a “China finger trap” economy. Our growth depends on monopolies and AI bubbles that feed our all-important stock markets. Attempting to grow the economy in a more stable manner could lead to lower stock prices and paradoxically lead to a recession. So until some external event occurs, we are stuck….

Data centers are now approaching multiple power companies with development proposals for the same project, leading to “phantom” forecasts of demand that don’t actually exist. In short, it’s hoarding.

Hoarding is what happens when markets get overheated…but this can cause something called the “bullwhip effect.” Buyers exaggerate how much they want to buy…and suddenly the demand evaporates because the demand was unrealistic to begin with. This dynamic can cause the economy to overheat and then fall into recession. That is what happened all over the world after World War I, leading in particular to Mussolini’s occupation of Italy…

Right now, we’re seeing about the same growth in data centers in America. I recently had a conversation with an elected official who told me that building data centers would significantly boost construction jobs in the rust belt…He posited a tension between political support for new temporary jobs and political anger over rising electricity rates.

We have a one-legged economy, where building AI serves as a driver for real estate values, stock markets, and GDP growth.

This is a plan that bets its economy against the model in which China has a better mousetrap. There’s no way this will end well.

____

1 This crisis demonstrated that theory and practice can be different. Banks have long offloaded credit card receivables to investors in what they call off-balance-sheet transactions. When those losses rose to previously unthinkable levels, investors revolted and succeeded in forcing banks to absorb some of the costs. That’s because banks’ credit card business depended on being able to continue using other people’s credit. It is unclear whether these AI data center borrowers will find themselves in a similar position where they are so dependent on continued financing that their lenders will not allow them to escape huge credit losses.