Eve, here. Many commentators have described the dire state of Venezuela’s oil industry and estimated what it will take to turn it around. The near-universal view is that significant changes in production will require years of large-scale, sustained investment. This post helpfully summarizes that issue, then looks at the U.S. refining side of the equation, identifying what it takes to process such heavy and troublesome crude oil and the percentage of U.S. refineries that are currently able to process it.

We’ll also repost a particularly informative tweet estimating the cost of a comprehensive upgrade of Venezuela’s oil production, including the often-ignored cost of upgrading and significantly expanding Venezuela’s power grid. Note that the objective is to replace Canadian heavy crude grades in the United States, as well as supply refiners established to handle a wide range of similar feedstocks.

I’ve spent a lot of time giving a shit about people who have opinions about Venezuela’s oil production potential and what that means for “RePLaCe CanADa.” Here’s my contribution – how I see the cost of replacing Canadian crude oil with Venezuelan heavy oil.

I think it’s close to $1 trillion… pic.twitter.com/XFlPVwPdew

— Michael Spiker (@ShaleTier7) January 4, 2026

The author is Alex Kimani, a veteran financial writer, investor, engineer, and researcher at Safehaven.com. First appearance: OilPrice

President Trump’s efforts to lure U.S. oil majors back to Venezuela have largely failed, with Exxon and ConocoPhillips claiming the country is uninvestable under current law and citing past expropriations. Venezuelan crude oil is attractive to complex U.S. refiners with coking capabilities, but only some plants in the Gulf and East Coast can fully process the sulfur-rich heavy oil. Rising supply from Venezuela would displace grades from Canada, Mexico and some Middle East producers, rather than broadly boosting U.S. demand.

Last week, US President Donald Trump’s appeal to Venezuelan oil company executives for the huge investments needed to revive the country’s struggling oil sector proved to have little effect. Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) CEO Darren Woods gave the harshest assessment, calling the South American country “uninvestable” under the current commercial framework and hydrocarbon laws, while ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) CEO Ryan Lance also gave Trump a reality check, reporting that his company suffered billions of dollars in losses when it pulled out of the country under Chavez.

Venezuela’s energy sector’s deep slide to rock bottom began after President Hugo Chávez’s government nationalized the oil infrastructure and assets of ExxonMobil (NYSE:XOM) and ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) in 2007. ExxonMobil (NYSE:XOM) and ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) have refused to accept new terms that would give Venezuela’s state oil company PDVSA a majority share of the project. The nationalization process began in early 2007 through a presidential decree and a new hydrocarbon law.

But Trump did score some notable victories. In short, Hilcorp’s Jeff Hildebrand said the company is ready to work on rebuilding Venezuela’s energy infrastructure, while Chevron (NYSE:CVX) said it could increase production in Venezuela by 240,000 barrels per day with “virtually 100% immediate effect.”

We previously reported that billions of dollars in infrastructure investment would be needed to bring Venezuela’s oil sector back to its 1970s peak production of 3.5 million barrels per day. Venezuela currently produces about 1 million barrels a day, and Chevron accounts for a quarter of that. U.S. refiners prefer Venezuelan crude because it provides a competitive advantage for complex refiners with sufficient coking capacity to process heavy oil into high-value products. Mary crude from Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt has one of the lowest API gravity and highest sulfur content in the world, requiring specialized refining equipment to break down the heaviest molecules and remove impurities.

Unfortunately, fewer than half of U.S. refineries have cokers, and refineries along the Gulf and East Coast are most likely to benefit from increased Venezuelan crude supplies. U.S. refineries with the highest coke production capacity include Valero (NYSE:VLO), Exxon, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum (NYSE:MPC), Phillips 66 (NYSE:PSX), and PBF Energy (NYSE:PBF).

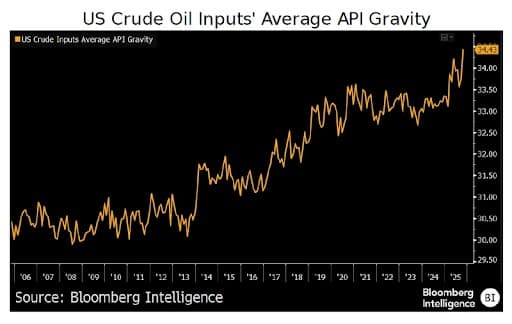

Coking and hydrocracking are petroleum refining processes that upgrade heavy crude oil fractions into lighter, more valuable products such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel, but they are used in different ways. Coking is a thermal carbon removal process that essentially burns heavy oil, leaving behind solid petroleum coke and a lighter liquid. Hydrocracking uses high-pressure hydrogen and a catalyst to chemically add hydrogen to break down large molecules into smaller molecules, producing cleaner fuels with fewer solid byproducts. Very complex refineries can achieve distillate yields of 33%, while plants of medium complexity can achieve distillate yields of 30%. A shortage of heavy oils, such as Venezuelan crude oil, is forcing many U.S. refineries to invest in additional equipment to refine lighter oils, such as U.S. shale oil.

Source: Bloomberg

However, increased availability of Venezuelan oil is likely to hurt demand for Canadian, Mayan, and Middle Eastern crudes. Despite improved access to Asia with the recent TMX expansion, the US still buys 80% of Canada’s crude oil production. This helps align WCS (Western Canadian Select) prices to U.S. refinery demand and alternative heavy grades. Meanwhile, increased inflows from Venezuela are likely to benefit mid-continent and West Coast refiners such as British Petroleum (NYSE: BP) and HF Sinclair (NYSE: DINO) thanks to wider WCS discounts if Gulf Coast demand is displaced.

That said, Venezuela’s low-hanging fruit is quite limited. According to Norwegian energy consultancy Rystad Energy, current production levels of 800,000 to 1 million barrels per day can be quickly restored with minimal expenditure to only 300 to 350 kilobytes per day, while production above 1.4 million barrels per day will require significant ongoing investment.

Rystad estimates that just keeping Venezuela’s production flat at 1.1 million barrels per day would require $53 billion over the next 15 years, but increasing production to more than 3 million barrels per day could require up to $183 billion over the same period, roughly equivalent to one year’s worth of land investment in all of North America.

Analysts at satellite intelligence firm Kairos said Venezuela’s energy infrastructure is in a “catastrophic state” after decades of underinvestment, obsolescence and cannibalization of equipment.

Kairos said numerous oil storage tanks at the Bajo Grande and Puerto Miranda terminals were failing due to corrosion and lack of maintenance. But this is an industry-wide problem. Kairos estimates that about one-third of Venezuela’s storage capacity is currently idle, reflecting unusable storage tanks, lower refinery utilization and reduced oil production. Meanwhile, operations at the large interconnected Amuay and Kardon refineries are running at less than 20% of capacity, effectively turning them into “de facto storage centres,” experts said.

Not surprisingly, Venezuela’s pipeline network is in a similar state of disrepair. Leaked documents from PDVSA in 2021 reveal that the country’s oil pipelines have not been updated in 50 years, and Venezuela’s National Oil Company estimates it will cost a staggering $58 billion to restore the pipelines to top condition. Recent estimates put the number at more than $100 billion. The total length of the oil pipeline network in operation in Venezuela is 2,139 miles (approximately 3,442 kilometers). To put it in perspective, the UAE, which produces about 3.2 million barrels per day, has about 9,000 km of oil pipelines.