Yves here. It may surprise most readers to learn that central bankers consider themselves to have done a tremendously good job in combating the Covid-induced inflation spike. This post tackles the disconnect between that view and how most citizens feel, as confirmed by Trump using inflation as an important campaign selling point and consumers in the UK and Europe still feeling very price squeezed. This post explains what it argues is an excessive central bank focus on the “sacrifice ratio” as in avoiding job losses and recessions when tightening rates, and why they might need to balance that concern with other issues, above all, actual price levels.

By Kristin Forbes, Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Professor of Management and Global Economics Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Jongrim Ha, Senior Economist The World Bank, and M. Ayhan Kose, Deputy Chief Economist and Director of the Prospects Group The World Bank. Originally published at VoxEU

By some criteria, the post-pandemic disinflation was a triumph for central banks in advanced economies: inflation fell sharply from 40-year highs while unemployment rates remained low, the combination of which generated historically low sacrifice ratios (output losses per inflation reduction). These standard metrics for success, however, ignore adjustments in the price level, which rose by more after the pandemic than over the past four decades. This column discusses lessons learned from the ‘start late and then sprint’ strategy for tightening monetary policy during this period, highlighting why the price level should receive more weight when central banks evaluate strategies for responding to inflation shocks – such as new tariffs – in the future.

When inflation surged across advanced economies in 2021–22 – peaking at levels not seen in four decades – the prevailing wisdom was that bringing inflation back to target would require deep recessions and substantial job losses. By 2025, however, inflation had fallen sharply, unemployment remained low, and many advanced economies had avoided the feared downturn (Bernanke and Blanchard 2024, Ball et al. 2025, De Grauwe and Ji 2025, English et al. 2024). Was it possible to stabilise inflation with no difficult trade-offs – or was there an overlooked cost?

This column draws from our new study (Forbes et al. 2025) to unpack what happened during the post-pandemic disinflation, why the adjustment was not painless, and what central banks should learn from this experience when responding to the next inflationary shock.

A Low Sacrifice Ratio…

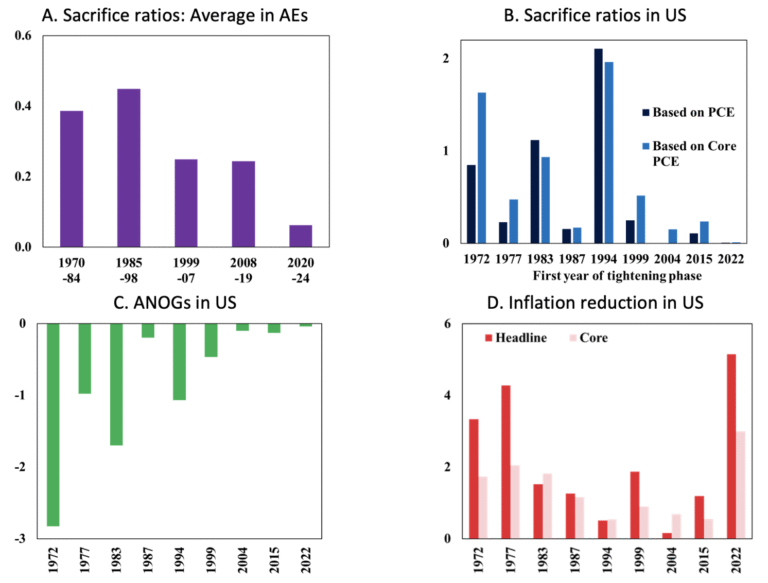

One popular way to measure the cost of disinflation is the ‘sacrifice ratio’ – the cumulative output losses corresponding to a one percentage point reduction in inflation. By this metric, the post-pandemic period looks like a triumph: sacrifice ratios during the recent period of monetary policy tightening in advanced economies have been the lowest since our data began in the 1970s (Figure 1A). 1 In some cases, they were close to zero – implying that no output losses were required to stabilize inflation. This was a sharp contrast to the experience of the 1980s – the last time that inflation reached double digits in many advanced economies – and which required painful recessions to stabilise inflation.

To better understand these developments, consider the case of the US. After the pandemic, the US sacrifice ratio collapsed to almost zero (0.01 to be precise) – well below the pre-pandemic average of 0.7-0.8 (based on headline and core PCE inflation, respectively) and lower than during any other tightening episode (Figure 1B). This collapse reflected a combination of historically small output losses combined with a large disinflation (Figures 1C and 1D). Patterns are similar across other advanced economies during this period, with a median cumulative output loss of just 0.4% of GDP and a median disinflation of more than 8 percentage points.

Figure 1 Sacrifice ratios during tightening phases

Source: Forbes et al. (2025).

Note: Panels A and B show the ratio of the accumulated negative output gap (in percent of GDP) to the reduction in CPI (or PCE) inflation (in percentage points) from peak to subsequent trough over tightening phases plus 12-month lag in a sample of 24 advanced economies (AEs) (in panel A) or the United States (in panel B). Panel C shows the accumulated negative output gap (ANOG) as a share of GDP over each tightening phase plus a 12-month lag. Output gaps are based on data from Havers using an HP filter. Panel D shows the reduction in headline or core PCE inflation in the US.

…But Much Higher Prices

Focusing solely on the sacrifice ratio, however, misses an important aspect of the post-pandemic adjustment: price levels rose sharply and have remained high. For example, in the US, the PCE price index rose about 17 percentage points between early 2021 and 2025 – roughly 8 percentage points more than if inflation had stayed at 2%. This is the largest annual price-level overshoot since the 1980s (Figure 2) – an adjustment which was particularly painful after consumers and businesses had become accustomed to inflation around (if not below) 2% in recent decades.

Why should policymakers care about the price level if inflation returns to target? First, most people don’t think in terms of inflation rates – they think in terms of how much groceries, rent, and gas cost today compared to a few years ago. Surveys show that price increases were a key factor contributing to high levels of public dissatisfaction with the economy during 2022–24, even as inflation fell. Recent research also documents that these concerns can affect election outcomes (Federle et al. 2024).

Second, and related, large and rapid price-level increases often erode real wages, consumption, and savings, especially if nominal wages adjust slowly. Even if real wages gradually recover (as they have on average in the US, albeit not in many other economies), consumers often consider their higher wages as ‘earned’ while the higher prices that erode their purchasing power are ‘unfair’ (Coibion et al. 2023, Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2025).

Figure 2 Evolution of the price level around US tightening phases

Source: Forbes et al. (2025).

Note: Changes in the PCE index in the US, set at 100 at t=-1. The t=0 indicates the first rate hike of the tightening phase for monetary policy.

Third, large increases in the price level can influence wage- and price-setting behavior. Firms adjust prices more quickly in response to future shocks, while households become more attentive to any subsequent price changes and workers become more assertive in wage negotiations. Finally, a sharp increase in prices can un-anchor inflation expectations, especially if people begin to question whether central banks will keep inflation low in the future.

While central banks should not set policy to improve their popularity or affect election outcomes, these last two channels suggest that changes in the price level can have first-order implications for issues at the core of central bank mandates. The behavioural shifts after large changes in the price level can amplify future inflation shocks and complicate the transmission of monetary policy to the broader economy. As a result, when central banks debate different strategies for responding to inflation shocks, they should carefully consider the impact on the price level, as well as the standard measures on which they traditionally focus (such as inflation, activity, and unemployment).

How Did This Happen?

These unusual patterns of historically low sacrifice ratios and large increases in the price level largely reflect global developments over 2020-22 – from the unprecedented economic lockdowns and reopenings around the pandemic combined with the sharp spike in commodity prices around the war in Ukraine (Bernanke and Blanchard 2024, English et al. 2024). Also important, however, was the ‘start late then sprint’ strategy adopted by central banks to tighten monetary policy.

As economies recovered from the pandemic, central banks were unusually slow to ‘liftoff’ (start raising interest rates) as compared to historical tightening phases. Figure 3 highlights how delayed this adjustment was based on the evolution of five macroeconomic variables.

Figure 3 Timing of first rate hike

Source: Forbes et al. (2025).

Note: Principal component of timing of first rate hike of each tightening phase based on: CPI (PCE) inflation, core inflation, unemployment gap, output gap, and GDP growth.

As central banks realised they were behind the curve, however, they quickly pivoted to raising interest rates. Figure 4 shows how the subsequent rate hikes were more aggressive than tightening phases since the mid-1980s for advanced economies – with median rates starting from around zero and increasing by about 450 basis points in just a year.

Figure 4 Policy interest rate during tightening phases

Source: Forbes et al. (2025).

Note: Median policy interest rate in a sample of 24 advanced economies during tightening phases.

Our empirical analysis suggests that this ‘start late and then sprint’ strategy played a meaningful role in explaining the low sacrifice ratios and corresponding sharp increase in the price level after the pandemic. The analysis also highlights, however, the pitfalls of focusing on sacrifice ratios as a measure of success. More specifically, the delayed start to raising interest rates contributed significantly to the low sacrifice ratio, but mainly by adding to the larger inflation overshoot (and increase in prices) that corresponded to the larger subsequent disinflation (the denominator of the sacrifice ratio).

Lessons for the Next Inflation Shock

What should central banks take away from this episode? 2 We highlight three lessons.

Be cautious about ‘starting late and then sprinting’. While this strategy for tightening monetary policy after the pandemic was successful in terms of achieving a large disinflation with relatively little damage to output or employment, it also entailed important costs and risks. The delayed liftoff allowed inflation to rise significantly higher and for a more prolonged period than it otherwise would have and therefore contributed to the large increase in prices (albeit much of this could not have been avoided due to global developments). The aggressive rate hikes that were subsequently required to catch up presented challenges for households and firms that were not expecting a sharp increase in borrowing costs, and increased financial instability risks (as seen, for example, in the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank).

Central bank credibility was key – but may be more fragile now. Key reasons why sacrifice ratios were so low were strong central bank credibility and well-anchored inflation expectations – both of which reflected central banks’ impressive track record of keeping inflation low over the previous two decades. Our analysis shows that without this strong credibility and anchoring of expectations, the subsequent disinflation would have required even more aggressive rate increases, more painful output losses, and a larger increase in the price level. In fact, central bank credibility is the one measure we assess that corresponds to no difficult trade-offs for monetary policy and only positive economic outcomes.

Unfortunately, however, the recent inflation surge has undermined central banks’ strong track record. Surveys and market data suggest inflation expectations are now higher (and in some cases well above 2%), more sensitive, and more diverse (Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2025). Central banks may need to rebuild and reinforce credibility going forward – especially if inflation continues to remain above target five years after the pandemic (as expected in countries such as the US and UK). A ‘start late, then sprint’ strategy could be much more costly in the future without the support of well-anchored inflation expectations.

Define success more broadly and consider adding the price level into communication and modelling. Central banks should continue to focus on returning inflation to target with minimal output losses. However, the recent experience suggests they should also prioritise minimising large and prolonged deviations of inflation from target – i.e. the impact on the price level. Different strategies for stabilising inflation can result in markedly different paths for prices, with significant implications for wage and price setting, monetary policy transmission, public sentiment, and the anchoring of inflation expectations.

This does not imply that central banks should shift to targeting the price level, which has well-known limitations. In some cases, a substantial adjustment in the price level may be the appropriate response to specific shocks. However, central banks could give greater consideration to the price level in how they communicate risks, assess policy trade-offs, and evaluate the performance of their frameworks.

When central banks next confront inflation – whether triggered by tariff-driven supply shocks, geopolitical tensions, sharp movements in commodity prices, or other factors – they will likely face difficult trade-offs once again. Ideally, their discussions on the appropriate strategy for monetary policy will go beyond the traditional focus on the output cost of bringing inflation back to 2% to also consider the duration of the adjustment and its cumulative impact on the price level.

Authors’ note: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this column are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed to the institutions they are affiliated with.

See original post for references