Eve here. This article discusses the complex arrangements between managers and users of the Colorado River water supply and how the effects of global warming and excessive commitment to its production are set up to create a dispute and potential court battles. With each treaty, Mexico wins at least 1.5 million feet a year. Given that Trump relies on legal overreach, I am amazed that he hasn’t done it.

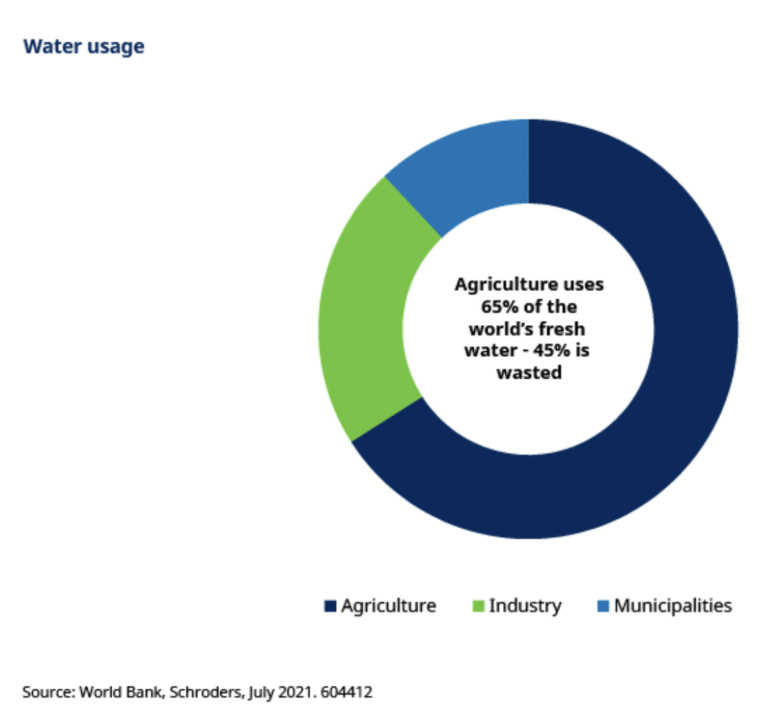

The history and current status of major contracts is a bit packed, so this article is light in its meaning. However, the Titanic’s feel to these issues involves rearranging deck chairs. My amateur understanding of the media is that agriculture is the biggest user. Certainly, this is true all over the world:

A related article on Schroeders explains how this is argued.

The growing global population is also putting pressure on the food system. Irrigation is one way to solve this. Agriculture doubles when irrigation is used, rather than relaying rainfall. But the challenge is to make sure this is done efficiently so that no water is wasted.

This is where technology plays a key role. Irrigation and drainage systems require greater investment. It’s not unsettling to just bid such a system. Ensuring they are maintained is important to make them run efficiently.

On the other hand, considering the limited supply of sub-brown water in many regions around the world, investment in escalated plant ISS is also important.

There is more advanced technology. For example, you can use soil moisture sensors to see when you need water and crops.

The entire water management system is expected to see a significant increase in demand. Recycling 45% of water, which is currently wasted, will help make global food and water systems more sustainable.

And it wasn’t just water that was wasted. Food waste is a problem with heage, and of course, when food is wasted, the water used in production is also wasted. Approximately 44% of the harvested crop is lost before reaching consumers. Again, technology is an important enabler to reduce that waste.

Another way is to try to find production of less water-hungry crops (although SEMON is not the Semon that STRM is the courage to apply taxes to better reflect true resource costs). Still, how do you measure it?

One approach explained by the Pacific Institute in an analysis of California’s water resource data is to normalize with one acre of water per acre of land. As summarized by the Democrats

1. Meadows (Clover, Rye, Bermuda, Other Grass), 4.92 acre feet per acre

2. Almonds and pistachios, 4.49 acre feet per acre

3. Alfalfa, 4.48 acre feet per acre

4. Citrus and subtropical fruits (grapefruit, lemon, orange, date, avocado, olive, jojoba), 4.23 acre feet per acre

5. Sugarbeat, 3.89 acre feet per acre

6. OTER deciduous trees (applicable, apricot, walnut, cherry, peach, nectarine, pear, plum, prunes, figs, kiwi), 3.7 acre feet per acre

7. Cotton, 3.67 acre feet per acre

8. On-run and garlic, 2.96 acre feet per acre

9. Potatoes, 2.9 acre feet per acre

10. Vineyards (tables, raisins, wine grapes), 2.85 acre feet per acre

However, using the final metric SEM will use a better way to compare usage. Look to the green bar on the table below.

Sarah Porter, director of the Water Policy Center at ASU Morrison Public Policy Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University. Originally published in conversation

The Colorado River is in trouble. There is no water flowing into the river enough that people are entitled to take it out of it. New ideas may change that, but complex political and practical denials are in the way.

The river and its tributaries provide about 5 million acres of farmland and pasture, hydroelectric power generation for millions of people, recreation in the Grand Canyon, and water for important habitats of fish and other wildlife. Collected by 30 federal governments, the Natizans claim rats to the water from the Colorado River system. It is also an important source of drinking water for cities in colored river basins, including out-basin cities such as Phoenix, Tucson, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, San Diego, Salt Lake City, Denver and Albuquerque.

Seven states in the Colorado Basin have been working on ways to deal with the decline in Colorado River supply for a quarter century, reviewing usage guidelines and taking additional steps as you continue to sustain and reservoir levels continue to decline. Current guidelines expire in late 2026, and consultations on new guidelines are stagnant where we cannot agree on ways to avoid future crises.

In June 2025, Arizona proposed a new approach, with the first time the amount of water available in the current flow of the river, rather than reservoir-level projections or historical allocations. Suggestions that are praised as what you offer

Colorado River Compact

The 1922 Colorado Compact divides the 250,000 square miles of Colorado River basin into upstream basins. It encompasses Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and parts of Wyoming, the northeast corner of Arizona, most of Arizona and parts of California and Nevada. The compact apportions absorb 7.5 million acres of water from the river each year. Acre feet of water is sufficient to cover a foot of water DEP, appearing in about 326,000 Gorons. According to a 2021 estimate from the Arizona Department of Water Resources, one acre foot is enough to supply 3.5 Arizona households for a year.

Predicting a future treaty with Mexico to share the Colorado River water, the compact specified that Mexico should first supply the available surplus, and the two departments specified the required additional amount “borne equally.” The 1944 Water Sharing Treaty between Mexico and the United States guarantees Mexico at least 1.5 million acre feet of water on the Colorado River each year.

The Compact also designated that Upper Basin conditions in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming “does not cause river flow… below the 75,000,000 acre feet total for the 10th consecutive year.”

The lower basin conditions of Arizona, California and Nevada claim that the provision is “delivery oblivion,” and the upper basin must regenerate it for ten years.

In contrast, the upper basin condition simply claims that, due to additional use by the Upper Basin Wool, a language that simply created a “non-depletion obligation” to collectively use at 7.5 million acre feet a year to be delivered to the lower basin over a decade, if it is less than 75 million acre feet.

This discrepancy to the language of compacts lies at the heart of the differences between the two basins.

Small sauce area

Almost all of the water in the Colorado River system comes from snow falling on rocky mountains upstream. Approximately 85% of the Colorado Basin flow comes from 15% of the basin surface area JUS. Most of the remaining land in the basin is arid or semi-arid, with accuracy of less than 20 inches a year, making little contribution to the flow of the Colorado River and its tribute.

Rain and snowfall differ dramatically from the annual reservoir, making it available in dry years as it catches extra water in rainy years. The most notable reservoirs in the system are the support of the Hoover Dam, which was completed in 1936, and the support of the Hoover Dam, which was promoted by the Glen Canyon Dam, which was completed in 1966.

Over the past 25 years, the amount of water stored in Lake Mead and Powell has decreased significantly. The main driver of this decline is the long drought that is likely to be amplified by climate change. One study is that the area may be suffering from the driest spells of 1, 200 years.

However, the human error ERU is also added. The original negotiators of the Colorado Compact made unrealistically optimistic assumptions about the average annual flow of the river – perhaps intentionally. Colorado River experts Eric Coon and John Fleck document whether compact negotiators deliberately wish in their book Science Be Dammed. Kuhn and Fleck argued that negotiators knew that demand had been abolished decades ago beyond river water supply, and they tried to sell a big vision of southwest development worthy of large-scale federal financial funding for Reervoires and other infrastructure.

In the expansion, the current Colorado River system accounting does not lose approximately 1.3 million acres of water from Lake Mead each year due to evaporation into the air and penetration into the ground. This accounting gap means that Lake Mead’s water levels are steadily falling under the usual annual release to meet allocations to the lower basins and Mexico.

Stabilization efforts

Seven Colorado River states and Mexico have taken signatories’ measures to stabilize the reservoirs. In 2007, they added to new guidelines to coordinate the operations of Lake Mead and Lake Powell to prevent them from reaching catastrophically low levels. They also agreed to reduce water volumes in Arizona and Nevada, depending on how the levels of Lake Mead progress.

If the 2007 guidelines implement that reservoir levels do not drop, the states of the Colorado Basin and Mexico will agree to additional measures, allowing releases from the upstream reservoir under certain conditions, and allowing additional reductions to downstream and Mexican water users.

By 2022, reservoir level forecasts looked so disastrous that the state began negotiating additional short-term measures to reduce the amount of water users withdrawing from the river. The federal government also supported: Funding for the $4 billion Inflation Reduction Act helped pay for water conservation measures, primarily by agricultural districts, cities and tribes.

These are the real realities. In 2023, Arizona and Nevada California used only 5.8 million acres of Colorado River water, the lowest annual consumption since 1983.

New opportunities?

With 2007 guidelines and additional measures expire in 2026, the new agreement is approaching. As Colorado River states try to resolve the new agreement, new proposals for Arizona’s supply-driven approach offer hope, but the Devil offers in detail. The key components of that approach are not resolved. For example, the percentage of river flows available to Arizona, California and Nevada.

If the state cannot age, the Interior Secretary, playing thissou, the claims office, could decide for himself how to balance the rewind and how much water it will deliver from them. That decision will almost certainly be brought to court by states or water users who are unhappy with the outcome.

And the lower basin states say they are fully prepared to go to court to enforce what you answered is the delivery obligation of the upper basin ready to fight.

In the meantime, farmers in Yuma County, Arizona and Imperial County, California, cannot be sure they will cover the water in the coming years to produce winter vegetables and melons. City water agencies in the Colorado River Basin are worried about meeting the water requirements of homes and businesses. And tribal nations fear that they don’t have the water they need for their medicine, their communities, their economy.