For the first time since Texas criminalized abortion, the state’s health care regulator is guiding doctors on when they can legally terminate a pregnancy to save a patient’s life. A woman died and doctors, who feared jail time for intervening, had sought guidance for years.

The new training by the Texas Medical Board comes nearly five years after the state passed a strict anti-abortion law in 2021, threatening doctors with harsh penalties. ProPublica reports that after the law went into effect, pregnancy became much more dangerous in the state. Sepsis rates among women who miscarried skyrocketed, as did emergency room visits where patients who miscarried required blood transfusions. At least four women have died in the state due to lack of timely access to reproductive health care. More than 100 obstetricians and gynecologists blamed the state’s abortion ban.

In response, the Texas Legislature passed the Mothers for Life Act last year. The law updates medical exceptions to the abortion ban, adds legal burdens for prosecutors to bring criminal charges against doctors, and requires medical boards to develop guidance for doctors by January 1, something no other state that bans abortions has done.

The new medical training, obtained by ProPublica through a public records request, ensures that doctors can legally provide abortions even when the patient’s life is not in immediate danger and covers nine example scenarios, including pre-term rupture of membranes and complications from incomplete abortions.

Some of the scenarios reveal how doctors can intervene in situations similar to the cases investigated by ProPublica. For example, in 2021, Joceli Barnica was diagnosed with an “inevitable” miscarriage, a high risk of dangerous infections, and death because doctors did not empty her uterus while the fetus still had a heartbeat. The new training includes examples showing how abortion would be legal in similar cases.

But medical and legal experts who reviewed the training for ProPublica said the case studies only represent the simplest situations doctors encounter. Many have warned that the complications that women face during pregnancy are diverse and complex and impossible to capture in a short presentation. One lawyer called the training “bare-bones.”

“I can probably name 100 situations that would make people stop and say, ‘Well, is that legal?'” said Dr. Tony Ogburn, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Texas. “They have years of medical training and experience on how to deal with these cases and they put it into 43 slides.”

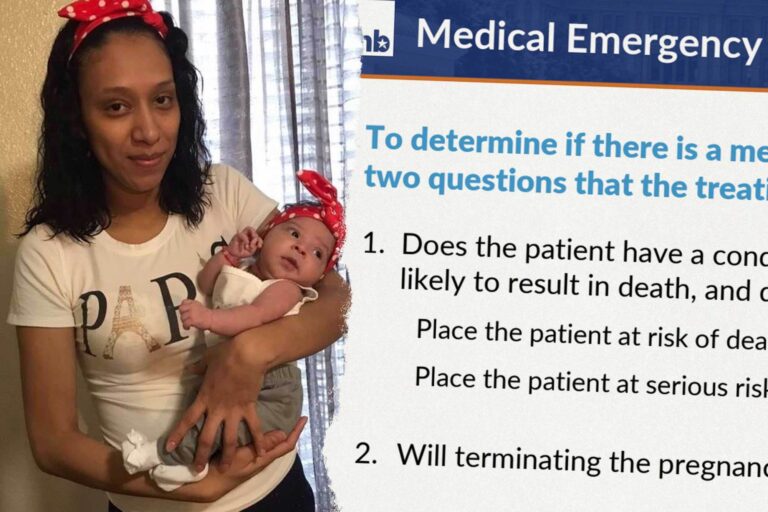

Notably lacking in the training is guidance on how doctors should care for patients with chronic illnesses, a gray area that has been highlighted repeatedly in ProPublica reporting. Last year, ProPublica investigated the death of Tierra Walker, a San Antonio woman with diabetes and high blood pressure who died after enduring repeated hospitalizations and worsening symptoms. Her family said doctors denied her request for an abortion to protect her health. The doctors and hospitals involved in Walker’s treatment did not respond to ProPublica’s requests for comment.

And no amount of training can solve what many doctors see as the main problem: the law’s harsh criminal penalties. If found guilty of performing illegal abortions, doctors face up to 99 years in prison, a $100,000 fine, and loss of their medical license. Even the prospect of a lengthy public legal battle could be a powerful deterrent, many doctors told ProPublica.

The Texas Medical Board says in training that if doctors practice “evidence-based medicine,” follow “standard emergency procedures” and properly document cases, “the legal risk of prosecution is extremely low.” The training also reiterates that the burden is on the state to prove that the abortion would not have been performed “in the absence of a reasonable physician.” Before the Maternal Protection Act went into effect, prosecutors could accuse doctors of performing illegal abortions with little evidence.

That assurance rings hollow to some doctors, who point to Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s actions since the state’s abortion ban went into effect.

Dr. Damra Kalsan, a Houston-based obstetrician-gynecologist, said she appreciates the training, which will allow doctors to use their expertise to make decisions in emergency situations. “But it’s still scary to have to defend your decision,” Kalsan said.

In 2023, Paxton overrode Kalsan’s medical judgment when patient Kate Cox sought an abortion at 20 weeks after learning her fetus had a fatal genetic abnormality. Texas bans abortions for all fetal abnormalities unless the pregnant woman is facing a medical emergency. Mr. Carthan maintained that Mr. Cox was eligible. She had previously had two C-sections, increasing her risk of bleeding, infection and future infertility. A lower Texas court allowed the abortion, but Paxton appealed the decision to the Texas Supreme Court, which ultimately overturned the decision, arguing that Kalsan had not done enough to prove Cox’s life was in danger.

Mr. Paxton’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment on the Cox case and the medical board’s assertion that the risk of legal action for doctors who follow its guidance is extremely low.

Dr. Sherif Zahran, president of the Texas Medical Board, told ProPublica that the training was reviewed by Paxton, Gov. Greg Abbott, state Sen. Brian Hughes, the author of the abortion ban, and others. The board is made up of 19 governor-appointed members, 12 of whom are licensed physicians but does not include obstetricians and gynecologists, and also consulted with the Texas Hospital Association and the Texas Medical Association.

Physicians practicing obstetrics, including all emergency room and urgent care physicians, will be required to complete a self-administered online course by 2027 to obtain or renew their license.

Multiple doctors told ProPublica that decisions about abortion care are also shaped by hospital lawyers. The Life of the Mother law requires the Texas Bar to create its own training for attorneys, which ProPublica reviewed. The presentation also explains that prosecutors considering criminal charges would need to prove that no other doctor would provide an abortion if faced with the same scenario.

Blake Rocap, a longtime reproductive rights attorney, said the state’s guidelines should give doctors and hospitals more protection to help patients get treatment. “It will save lives,” he said.

Since Texas’ six-week abortion ban went into effect in 2021, doctors, hospitals and reproductive rights advocates have repeatedly called on the Texas Medical Board to provide guidance on how medical professionals can comply with abortions. In particular, it asked for clarification on the law’s vague exception for “life-threatening emergencies.”

For years, the board has refused, saying it doesn’t have the authority.

Without guidance, the entire state was thrown into chaos. For example, according to leading medical organizations, the standard treatment for patients who miscarry in the second trimester is to offer to empty the uterus to reduce the risk of infection and sepsis. Some doctors in Texas told ProPublica last year that they routinely suggest emptying the uterus in such cases, but others said hospitals wouldn’t allow them to do so until the fetus’s heartbeat had stopped or life-threatening complications could be documented, leading to delays in treatment like the one Varnica experienced. A ProPublica data analysis found that after the ban went into effect, the number of sepsis cases caused by second-trimester miscarriages jumped more than 50% across the state.

In 2024, the board issued limited guidance stating that health care providers do not have to wait until a pregnant woman is on the brink of death to intervene. The new training goes further by providing detailed examples of when abortion is legal.

One case study features a patient who had an out-of-state abortion but had tissue remaining in her uterus. Because the pregnancy has already ended, the medical panel recommends that “continued treatment with residual products is not an abortion and cannot be considered aiding or abetting an abortion.” ProPublica investigated the death of Amber Thurman, who died of sepsis in Georgia after doctors delayed emptying her uterus after an incomplete abortion.

The training also clarifies that the definition of an ectopic pregnancy (which is always life-threatening) includes implantation in an abnormal location outside the uterine cavity. Previous legislation defined an ectopic pregnancy as an ectopic pregnancy. Most ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes, but some may implant within the uterus (such as in scar tissue from a previous pregnancy).

Still, the training does not address important issues in miscarriage management highlighted in the ProPublica report. That is, in many cases, early miscarriage cannot be conclusively diagnosed with a single ultrasound examination. It may take several days to several weeks to confirm that the pregnancy has ended. In such cases, some doctors have not offered a D&C, a procedure that would prevent bleeding, leaving women bleeding and in pain. Another Texas woman named Porsha Gumezi bled to death during a miscarriage in 2023 because her doctor failed to provide a medical exam, according to the coroner.

The training also does not provide guidance on how to care for patients who are at high risk for pregnancy due to underlying conditions such as autoimmune disease, poor blood pressure control, or heart disease. Pregnancy often worsens these chronic conditions and can lead to slight death in some cases, although doctors may not consider this to be “life-threatening.”

Walker, a San Antonio woman ProPublica reported last year, had uncontrolled blood pressure, suffered from seizures and blood clots. More than 90 doctors were involved in Walker’s care, but not one offered her the option of terminating the pregnancy, according to medical records. Doctors who reviewed the new training for ProPublica said it was not yet clear when they would be able to intervene in cases like hers. When a woman first becomes pregnant, is it because she already has some risk factors that make the pregnancy more dangerous, or does she have to wait until certain symptoms appear that indicate her health is deteriorating?

Zahran said the training made it clear that doctors can determine whether a patient is at risk of death or irreversible damage, and can intervene before a patient reaches that point. “In other words, we don’t have to wait until someone has a blood clot or a stroke or something to decide we need to do something.”

What doctors should do, Zahran reiterated, is document those risks in case patients are considered for abortions. But Karsan claimed that she did so in the Cox case and that Paxton fought her in court anyway.

The medical board’s training includes two case studies of patients with fatal fetal abnormalities, but neither addresses whether the latest law would allow abortion in a scenario similar to Cox’s. Dr. Karsan noted in her medical records that a third C-section would put Cox at risk of death or, if there were complications, a hysterectomy, a claim she shared in court. The training emphasizes that a fatal fetal abnormality alone does not qualify for an exception and that “the mother must have a life-threatening physical condition.” Zahran declined to comment specifically on Cox’s case, but said he understood there was not enough documentation.

Cox told ProPublica that she trusted the judgment of her medical team and did not want to jeopardize her health by continuing with the pregnancy. Cox said it was “incredibly scary” to grieve an unexpected loss while being denied treatment and to see her doctor threatened by the state’s top lawyer. She eventually left Texas to get an abortion.

“I’m grateful to the doctors. Their hands were tied in so many ways,” she said. “The problem isn’t doctors. It’s that pregnancy is too complicated to legislate.”