Propublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates power abuse. Sign up and receive the biggest story as soon as it’s published.

The National Institutes of Health launched a five-year, $37 million stillbirth consortium in a pivotal effort to reduce what is known as the country’s “unacceptably high” stillbirth rate.

Last week’s announcement thrilled doctors, researchers and families and represented the agency’s commitment to prioritizing the expected death of child deaths in more than 20 weeks.

“What’s really exciting is that we’re not only investing in preventing stillbirth, but we continue to work with the community to guide our research,” said Alison Cernich, acting director of the NIH Eunice Kennedy Shrier National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, in an interview.

Four clinical sites and one data coordination center, from California, Oregon, Utah, New York and North Carolina, come together to form a consortium, each bringing their own expertise. Most people focus on how to predict and prevent stillbirth, but they also plan to deal with bereavement and mental health after a loss. Studies show that out of more than 20,000 stillbirths in the United States each year, 25% can be prevented. For deliveries over 37 weeks, that number jumps in almost half.

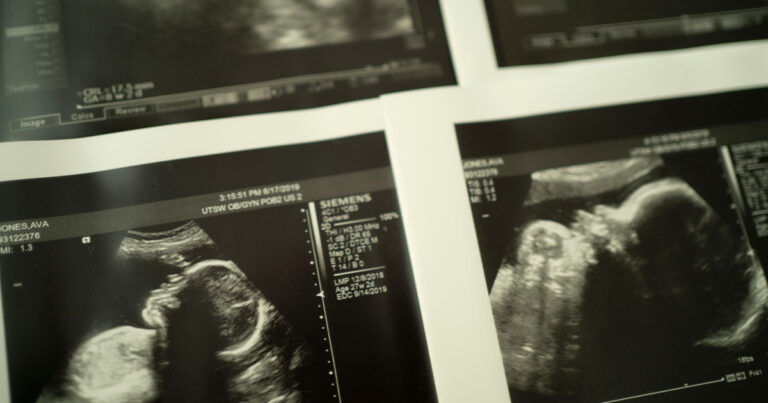

The team plans to meet for the first time on Friday and discuss possible research goals. These include understanding why some placentas break down and the fetus does not grow properly. Evaluate fetal movement reduction; consider the optimal time for delivery and use advanced technology to explore how blood tests, biomarkers, and ultrasound can help predict stillbirth. You can also assess how electronic medical records and artificial intelligence can help doctors and nurses identify early signs of stillbirth risk. The announcement did not mention racial disparities, but the representative said they hoped the consortium would identify factors that determine who are at high risk of stillbirth.

For many families, there is a lack of answers, such as how and why the loss occurred after the devastation of stillbirth. The team will work with the stillbirth community through an advisory group. The North Carolina team oversees data collection and standardization. Incomplete, delayed, and sometimes inaccurate stillbirth data were obstacles to preventive efforts.

“If we can see the signs and deliver the baby in a way that mothers have a living baby, then that’s what we want,” said Dr. Cynthia Gyamfi Bannerman, chairman and professor of obstetrics and gynecology, gynecology and reproductive science at the University of San Diego, California.

The consortium follows a nationwide shift in conversation around stillbirth. Propublica began reporting on stillbirths in 2022, and in 2025, the news organization released a documentary following the lives of three women trying to make pregnancy safer in America after stillbirth.

See “American Stillbirth Crisis: Before Breath”

Featured in the documentary, Debbie Heine Vijayverjaya has asked Congress to support the Stillbirth Act, urging lawmakers to pass the autumn action (brightness), named after the fall joy of their stillbirth daughter. Two days later, the NIH announced a consortium, Republicans and members of the Democratic Congress reintroducing the bill.

“It feels like our moment has finally arrived. We are part of this very important lifesaving task that is being done,” she said.

Congress previously mandated a stillbirth working group formed by NICHD in 2022, and we heard directly from stillbirth families. The working group has issued a federal report calling the country’s stillbirth fees “unacceptably high.” The United States is far behind other wealthy countries in reducing its mortality rates.

Dr. Bob Silver, a leading death specialist at the University of Utah Health, has been working on stillbirth prevention for decades. He is co-director of the University of Utah Still Birth Center of Excellence, focusing on both post-defeation prevention and compassionate care, leading the consortium efforts in the state.

“There’s no doubt that Propublica’s report was closely tied to this,” Silver said. “You can’t always draw a straight line between those things. But in this case you can draw a very straight line.”

Although several studies, including the NIH human placenta project, have contributed indirectly to stillbirth research, the consortium is the first stillbirth-specific initiative of this scale since the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network over a decade ago. Both Silver and Dr. Uma Reddy, professors of obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University, worked together in the research network and once again collaborated in the consortium.

“We need to be able to lower fees to similar high-income countries,” Lady said. “This initiative is really important to consider reducing stillbirth rates and preventing them, and that’s really time.”

Dr. Karen Gibbins, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University, had just finished the morning clinic when she received an email a few days before the official announcement informing her that both she and OHSU were selected as part of the consortium.

Gibbins, who Propublica wrote to defend more autopsies after the death of his son Sebastian, could hardly believe it. She logged on to the federal grant website for confirmation, then went outside her office to give the department’s director a hug.

“Nextborns are a very big public health issue and have not been attracting much attention historically,” Gibbins said. “The fact that we have the investment in this centre to take this different approach to combat stillbirth, to prevent stillbirth and to provide better care to families experiencing stillbirth is a hope that we all need.”

Things you need to know about stillbirth

Gibbins and her team specialize in studying the role of chronic stress, nutrition and heart health.

NIH is distributing the first year of funding of approximately $7.3 million, including $750,000 provided by the Department of Health and Human Services. Despite cuts at the NIH, authorities said they were optimistic that they could fund the project for the remaining four years.

“The reason we’re doing this is because stillbirths affect one of 160 deliveries per year, and it’s really traumatic for the family and that’s not talked about,” Sernich said. “We are in a great place to really tackle this preventable tragedy.”