Eve here. This post is presented more as a critical thinking exercise rather than the results of the research posted below, although they are also interested. As you can see, a study perforated in Germany using data from 2000 to 2005 found that the world lost was not earning as bad a fee as the average results suggest.

I say, “Huh?”

First, even the relatively favorable 25% often contributed to losses of income and perhaps relative savings against some, if not all, of five years. To reach a better conclusion, you need to estimate your lifetime revenue and see if there is a general, ordinary outlook based on the period of no income/low income and the extent to which you have subsequent income, and the extent to which you compensate.

Secondly, 25% still see strict photos. 75% have confirmed that it is getting worse over the long term.

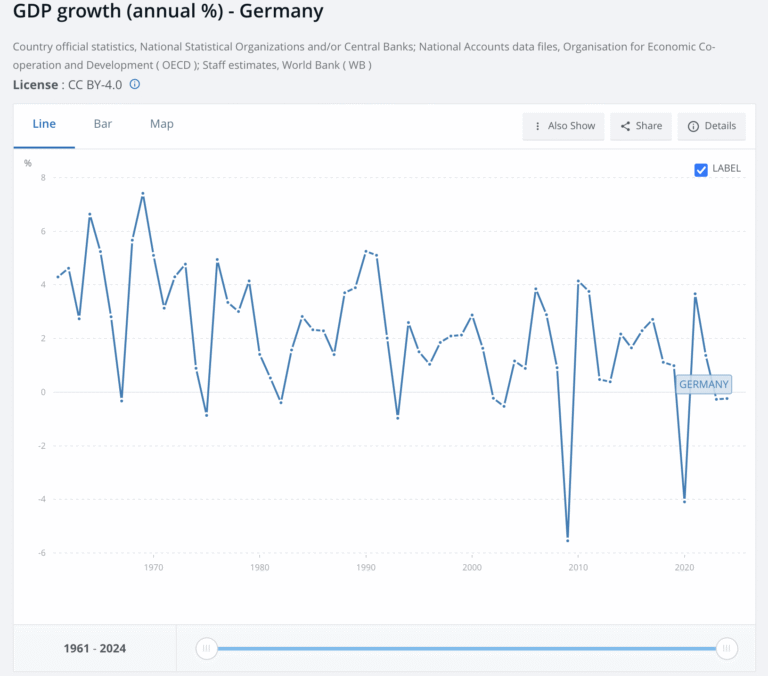

Third, the research time frame happened to occur during the period of great growth in Germany. From the World Bank:

Fourth, the expression of collective bargaining in Germany that you have fallen since 2000 generally suggests a weakening of labour rights (readers who know more about the situation in Germany have discovered that TU speaks. A report from the European Union Trade Council in 2020 found that the global proportion of Germany, which is covered by collective bargaining agreements fell by 14% to 54%, below the EU’s average of 61%. Therefore, Germany is far from the workers’ paradise that encompasses it. The EU says it has much higher collective bargaining levels, including Denmark, Finland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovenia, Spain, Italy, Austria, Netherlands, Finland, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Sweden, etc. Austria leads the pack at 98%.

Be careful, I’m not the findings (after all, the findings are the findings), and Spin looks at the mislabeling of job losses as “work movements.” “Employment evacuation” implies that all of these companies will ultimately find new jobs.

In Adionion, one thing to say is, “Previous information about this topic may not be as scary as it appears.” In contrast to the shares taken here, the unevenly distributed long-term outcome from unemployment means that they are not big names. Less claims are still bad.

Examples of what I mean:

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility-industry, occupational and regional changes multiple times, while the adjuster makes a critical move after displacement, while the casualty experience experiences delayed and unstable transitions.

Therefore, if they don’t land well, it’s entirely the workers’ fault. The author’s attitude is that the delay was not acting “conclusively.”

Certainly, there were probably shocked and controversial sub-job losers before taking serious about new security employment. But from observing unnatural exits, how fast is one land, how quickly is the function of luck and the usefulness of your own personal network.

Hoover Institute Stanford University, Eric Hannshek, Paul and Jean Hannah Sr. Fellows. Simon Jansen, Senior Research German Employment Institute (IAB), and Jacob D. Wright. Originally published on Voxeu

Decades of research have confirmed that work transfers are important causes and sustained revenue losses. This column presents new evidence from the world that evacuated during business closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005. This suggests that long average losses have been docoded before, before being influenced by world minorities, which are in fact much more uneven than before, and catastrophically reduced revenues.

Repeated, urgent policy debates revolve around the long-term outcomes of the world after work transfer events such as corporate closures and large-scale layoffs. Historically, studies have shown that such displacements show substantial triggers and sustained revenue losses for affected workers. Extensive literature – traces back to Jacobson et al. (1993) and include influential recent research by Davis and Von Wachter (2011) for the United States and Schmieder et al. (2023) Regarding German documents, sustained revenue loss of 15-25% after the exhibition, and older, low-educated workers are disproportionately affected.

However, much of this literature focuses on average efforts with different groups of workers, leaving a signature gap in understanding the distribution and heterogeneity of these losses. A recent paper (Hanushek etal. 2025) uses new empirical methods and comprehensive management data from Germany to characterize the full distribution of revenue losses for displaced people. Our findings suggest that traditional narratives of displacement centered around modest losses are huge differences in the world after these jobs, hiding the fact that about a quarter of the displaced people appear first after the 5 Five.

Distorted distribution of profit losses

We look at workers who were expelled from all business closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005. Our analysis employs a new combination of matching control methods at the individual worker level.

Our central finding is that the distribution of revenue losses is highly skewed. In other words, focusing solely on the outcome of Avenge means giving us an incomplete and misleading view of the world’s current experiences. The large average losses explained in previous studies are heavily affected by a small number of world people experiencing catastrophic income declines. In fact, the cumulative revenue loss for modal workers over the course of five years is just three months of pre-closure revenue. Many of the evacuated workers earn even more than their comparable non-distributed workers after evacuation. This discovery consists of Farber’s (2017) discoveries, where many have evacuated our world, ensuring better paying jobs quickly.

Figure 1 shows the points graphically. Dot plots average the difference in revenues between comparable and comparable groups of undisplaced workers over the years before and after displacement, and gray/red shading areas plot the perfect distribution. Dots show a steep and sustained decline in average displaced person revenues, but the distribution of these losses is very wide. Massive losses are concentrated in a small number of worlds, and many workers experience little confusion.

Figure 1. The distribution of relative revenues after the company closure is lost

Note: This diagram shows the distribution of revenue losses for displaced people up to five years after the company closure before the period five years ago. Loss of revenue is measured compared to the average revenue of individual workers three years prior to the displacement. The dots represent the average revenue loss for each public. Shady areas represent the distribution of estimates of revenue loss for displaced people.

Source: IEB.

Limited predictive power of observable properties

Previous studies documented differences in displacement effects for workers in different demographic groups – older workers, women, and Thue with lower educational achievements usually suffers greater average losses. This literature also highlights losses in firm-specific wage compensation as a major factor in post-displacement losses (e.g. Lachowska et al. 2020). Our findings are consistent with these average patterns, but also highlight limited explanatory power. Observable worker and enterprise characteristics explain less than 20% of the total fluctuations in global revenue losses that have been displaced.

Even among displaced people from the same company, we find surprisingly diverse results, even with similar demographic characteristics in the same role. Even stable wages will quickly move towards stable new employment, while others face unemployment and severe wage penalties. This heterogeneity within the group poses challenges for policy makers designing unemployment assistance programs, as targeting solely based on worker or company characteristics cannot direct resources to those who need it most. Instead, before observable factors and luck, it appears to drive a significant portion of heterogeneity in the postdispersional outcome of the world.

Distinguishing “adjuster” from “victim”

To further explain the heterogeneity of displacement outcomes, we classify workers into two groups based on EYR severity. These groups are demographically similar, but the diversified labor market trajectory is richly different.

The adjuster responds quickly. Switching occupations, industry, and even the post-displacement regions. The adjuster will quickly stabilize in these new positions, typically regaining or exceeding pre-diversification wage levels within five years. In contrast, casualties have regained stable employment, experiencing long-term unemployment and unstable, low-paid jobs. Figure 2 documents this being divided into a variety of different adjustment margins.

Figure 2. Percentage of switch companies, industries, occupations and regions in the world after the closure of the world

Note: This figure compares the frequency of different responses to corporate closures by the adjuster and the victims regarding corporate closures (time = 0). All changes are subject to adoption that year. The box in the upper left corner summarizes the changes in the average cumulative number of changes after variance for each group over 5 years.

Source: IEB.

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility-industry, occupational and regional changes multiple times, while the adjuster makes a critical move after displacement, while the casualty experience experiences delayed and unstable transitions. This finding was Fallick et al. (2025) highlights the role of widening unemployment spells in aggravating displacement losses. Consistency with the study by Minaya et al. (2023) , we do not see many workers pursuing continuing education as a means of adapting to shelters.

The effects of company-specific factors are also subtle. The victims go to lower wage companies, and the associated wages are below the first company’s revenge. The adjuster goes to slightly higher paying companies, but wages are significantly higher than the average worker in previous companies.

Conclusion

Decades of research have confirmed that work transfers are important causes and sustained revenue losses. However, our new evidence suggests that the losses are much more uneven than previous explanations. By focusing on average effectiveness, researchers and policymakers may miss substantial variation in displacement experiences among observable similar workers. Navigating layoffs involves personal, resilience and luck. It is a predictable factor and complicates the design of effective assistance programs. This is because it is difficult to predict who will be properly coordinated and who will withstand permanent confusion.

See original bibliographic submission