A recent post by the Financial Times’ highly respected lead economics commentator, Martin Wolf, Why are fertility rates collapsing? Gender roles, provides a detailed, if also perhaps unduly conventional, view of why birth rates have plunged all over the world. Even though most of what Wolf and others like him have said is true, we think it misses key issues due to sentimentality and cultural indoctrination about parenthood and child-rearing creating blind spots.

Due to wanting to avoid a sprawling post, we will ignore the elephant in the room, that for the health of the biosphere and to have any hope of limiting further damage to the planet, that humans should welcome and find ways to manage smaller population levels. Laments like those of Wolf are anachronistic. But they not only reflect a reluctance to embrace falling birth rates, but also sidestep how many modern childrearing practices are unduly costly in labor and human development terms.

On top of that, the modern ease of getting divorced is a disincentive for women to have children. In the US, one out of seven single mothers winds up bankrupt. In a divorce, it’s the husband who has an option of continuing to involved in parenting (unless the mother is pretty horrid, courts have a strong bias to award custody to her). He can exit and leave the work to her.

Yes, it is true that now that female labor has become more valuable due to reproductive control providing for much improved access to stable work and higher pay levels means that motherhood is most “costly” to them than it once was. The women’s liberation movement also did raise gender role expectations among women to levels that that generally have not been and never will be.

Kids are starting to become a Giffen good, with higher income families having higher fertility rates. This trend was anticipated decades ago by a friend, Christina, who was the first woman on Wall Street to become a partner in M&A, at Lazard. She also even by the extreme standards of that field had an astonishing work ethic. Most of those who knew her were stunned when she became pregnant. I was a guest at the prospective parents’ country home when the very pregnant Christina reported on a call with her mother-in-law, who apparently had quizzed her pointedly on why she was having a child. The reply: “Because it costs more than a Chanel bag and all my friends will be jealous.”1

It’s not sufficiently acknowledged how much sacrifice doing an adequate job of childrearing entailed. I sometimes remark that turning children into human beings requires decades and does not always take. Admittedly, in the days of subsistence farming, that problem was “solved” by putting kids to work as soon as they were able, for the practical reasons of both teaching them needed skills and exploiting their labor.

Historically, aristocratic parents did not bring up their progeny but relied on servants. For instance, both the father of diplomacy Talleyrand and Churchill recounted how rarely they saw their parents. Talleyrand’s club foot may have been the result of being dropped by wet nurse in his infancy.

That is not to say that some do not genuinely find being around kids a lot (as opposed to in small doses) to be enjoyable. But that personality type needs to be recognized as in a minority. And that’s before considering that small children are also body fluid intensive.

And that is before getting to additional modern factors that skew the equation away from parenting being experienced as rewarding. The first is the new norm, at least in the US, for parenting being a high-supervision activity. Like many readers, I grew up in the days when kids were allowed a lot of independent action within certain parameters. Even as a six year old, I was allowed to be out and about in the ‘hood as long as I was home in time for dinner. That provided a break for adults. Now “free range” children is a derogatory term. Yet children being denied this amount of autonomy and limited risk-taking cannot be a plus for their development, even if contemporary parents take pride in filling scheduled enrichment, like music lessons and play dates.

The fact that devices provide cheap and easy engagement, as we and many many others have discussed, is causing additional harm to many children by both overstimulating them and leading them to focus on screens as opposed to developing other critical skills, from reading to negotiating. But less often discussed is the fact that parental use of iPads as baby sitters is not just a reflection of the cost and difficulty of finding good day care. It also signifies that the parents find device engagement more satisfying than dealing with humans, in this case their own offspring. A new article in Unherd discusses this predisposition in an unusually candid manner. From Am I allowed to hate fatherhood?:

In recent years, women writers have made a highbrow cottage industry of the family-stress confessional…

These authors draw on a rich literary tradition of women venting about parenthood and marriage….

Why, then, do we hear so little from struggling fathers on this question?…Can we express the anxieties and downsides of fatherhood, the ways in which it crowds out our independence and creativity, instead of blowing up our families for novelistic material?

The answer is no, as I learned to my chagrin this month, when a chorus of disapprobation greeted a reflection I posted on X about just this issue.

It began with my four-year old son asking me to play catch in the street. I was drinking my coffee, still waking up, but I said sure. I also posted: “Playing catch with your son is supposed to be an iconic, peak experience.” But I wasn’t enjoying it, as I also confessed in my post. I wanted to be drinking my coffee in peace. The truth, I said, is that I just don’t like being around my two little kids, alone, for very long. I asked the internet whether I was a monster, or whether my feeling was within a certain range of normality.

The post garnered more than 19 million impressions. Men, many of whom granted that my feeling was normal, accused me of being weak and unmanly for complaining in public. Women said I was pathetic: mothers spend so much more time with children, and yet I could barely endure 10 minutes before needing to complain. I hit back that contemporary mothers have no idea what it is like being a father today, and was called a misogynist. Both genders agreed that I was selfish and immature, focused on petty and short-sighted matters like having my coffee in peace or getting back to my work.

Frankly, the lack of self-awareness the author exhibits is astonishing. He presumably was not conned by his wife into getting her pregnant and then somehow emotionally manipulated into hanging around to try to be a proper father, as opposed to offering merely to write checks. He is open about his resentment of being expected to be a provider as well as spend time helping raise his kid. If you had such a poor understanding of what the deal was, given your wife’s givens (presumably having to need to work while being a mother to help keep up the household income), why were you on board with the “becoming a parent” project?

Now I can’t prove it, but it seems a reasonable guess that the author’s resentment about a comparatively small time demand by his child is at least in part the result of device fixation. Most people are no longer used to having short bits of idle time, and now fill that with mental junk food, as in fooling with devices. As we can see with how many people stare at screens as opposed to talk to the people they are with, like their own family members at dinner, or crowd-watch. So the demand of being a parent now compete with entertainment-by-device, and the kids are less pleasurable, hence less valued in the “what gets my attention” hierarchy.

Today, despite ongoing attempts to denigrate childless couples and individual as unfulfilled, surveys have regularly found that couples without children are happier than those with kids, although the ones with offspring do report having a greater sense of purpose. Mind you, in groups so large there are many cases of particular couple with children being happier than those without.

We’ll now turn to Martin Wolf. Even though he assembles useful data, perhaps the discussion above will help convince you that his “it’s about gender roles” is such a superficial, if also entirely conventional, gloss as to not provide for good guides for action, particularly policy. From his article:

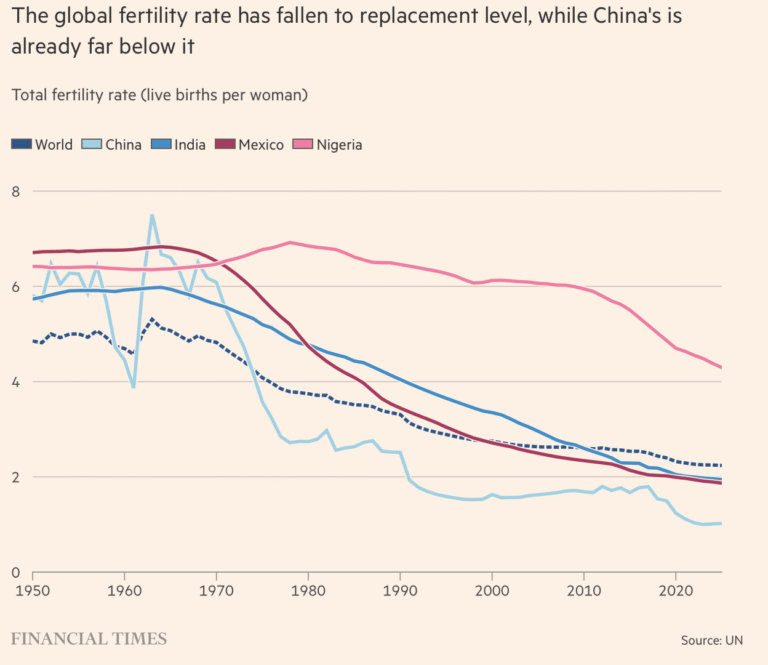

The decline in fertility has occurred in almost every country in the world. Furthermore, notes the Nobel-laureate Claudia Goldin, in her 2023 paper “The Downside of Fertility”, every OECD member (bar Israel) has a total fertility rate (average number of children per woman in a lifetime) of less than 2.1 (the replacement rate)….

Yet these changes do not fully explain what is going on, not least the markedly lower fertility rates of graduate women and the extraordinarily swift collapses in fertility in fast-growing economies with traditional gender norms, notably that wives should look after the children. In such countries, not only do the costs of bringing up children tend to be high, but they fall overwhelmingly on women.

I have to stop. Maybe it is just me, but it seems remarkable to see Wolf go on about gender norms, as opposed to putting this development in the neoliberal frame. Women gaining reproductive control allowed them to become “better” prospective employees, as in less likely to drop out because they became pregnant. Even though the pressure from the women’s lib movement provided a big tail wind, women would not have been so readily welcomed into the workplace save for the addition to the workforce moderating pressure to raise pay. If women had continued to be relegated via successful, discriminatory workplace practices, that kept them largely relegated to pink collar professions, and put a low glass ceiling on other type of work, do you think we’d see as many opting for careers?

As indicated, childrearing is taxing and if anything even more undervalued by society. Wolf and his “gender role” pom pom waivers don’t sufficiently acknowledge that. This may seem like a mere 30 degree change from his perspective, but differences like that are consequential.

Here is how Wolf frames the opportunity cost issue:

The simple (and obvious) point is that educated women who end up with the full responsibility for childcare for multiple children have relatively more to lose than their non-college-educated peers. This is why they are more likely to insist on marriage. It is also why they tend to have fewer children (though that is also because they start later).

I also doubt the assumptions about sequencing, that women get educated and then decide whether to have kids. Perhaps I am revealing myself as having a prototypical “second wave” feminist perspective, but I know many women who are educated who were clear in pursuing a career that they did not want to reproduce:

[Nobel-laureate Claudia] Goldin argues that women who gain professional incomes are better off and have much more agency. But if they are to do so, they need to postpone working in order to pursue their education, which increasingly they do. Once they are educated and in the labour force, they need to choose whether and with whom to have children. If they are to work successfully after having children, they will depend on the active help of their partners. But they cannot be sure the latter are reliable. Their partner might be a devoted helpmeet but he might leave her in the lurch. If his support fails, women will find it hard to sustain their career. So, graduate women hedge. They not only insist on marriage, but have few children, often one or none….

Now consider the cases of countries that had huge economic growth from a low base, as in southern Europe and east Asia. There, she argues, social mores are often stuck behind contemporary realities. Men still hanker after the patriarchal norms of a traditional society. Women enjoy the liberation of a modern economy. Goldin notes that countries particularly affected by this expectations mismatch (such as Japan, South Korea and, I suspect, China) also have high rates of female childlessness.

Again, there is a hidden assumption here, that having children is rewarding but a career maybe even more enticing. But again the point is blunted by “liberation of a modern economy” as opposed to seeing that it really does take a lot of work, no matter what the income level or accomplishment aspirations of the parents, to raise children that become competent, self-supporting adults. The message of women in aggregate is that society no longer values this activity adequately for enough of them in aggregate to value it enough to have the number of babies that businesses and policy makers want.

Recall that the overarching message of Karl Polyani’s classic The Great Transformation was that the operation of modern economies was to grind away at the social order. In the long time frame he covered, that process was never arrested or reversed, but reforms sometime did slow the pace of destabilizing changes enough to make them tolerable, at least at an overall level.

Now one can argue that this is indeed “unnatural” given physical reproductive urges. But pretty much everything we do in modern life is unnatural, from living in apartment buildings or manicured suburbs to turning up at work at a set time, regardless of the season. Much of what passes for civilization is a fight against the domination of nature, including lately, billionaires’ fixation with achieving super longevity.

As indicated early on, my druthers would be for respecting nature by embracing the fall in birth rates for the health of the planet. But we don’t yet seem to have remotely serious enough consideration of how to get there.

____

1 Christina did prove to be a good mother, always having breakfast with her eventual two girls and getting home early enough to help with homework. Both kids turned out to be well-adjusted and accomplished. But admittedly was considerably aided by having a stay-at-home husband who walked them to school, and by paying up to have two excellent nannies who stayed with the family throughout their childhoods. Christina was also famously frontal in negotiations and in other settings. For instance, at a Radcliffe seminar on work/life balance in the 1990s, she got up and said nothing would change until women owned the means of production