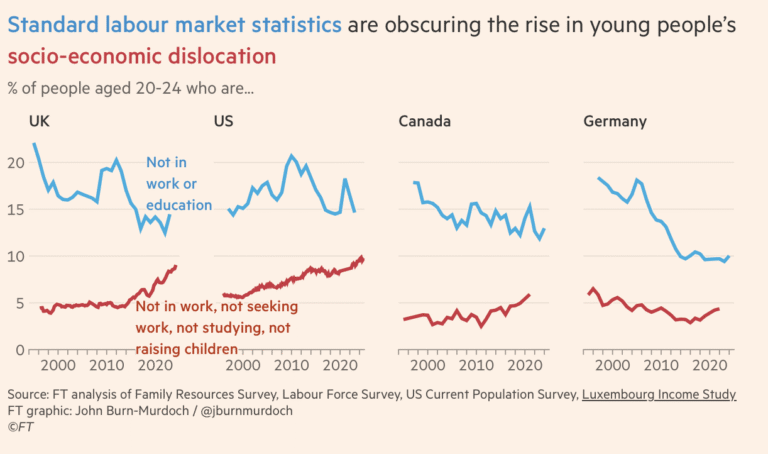

The Financial Times has published a new article about a growing social problem in many countries: the fate of young people who graduate from university or high school but are unable to find work. Although good data on this cohort is difficult to come by, there is ample evidence of high youth unemployment in Western countries as well as in China, pointing to the risk of these people becoming socially isolated and never integrated into ‘normal’ life.

This is further evidence of the pattern laid out in Carl Pogliani’s classic The Great Transformation. Mr. Poliani explained how capitalist operations are destructive to society, and that the process has been slowed but not stopped or reversed by reforms or regulations.

What we are seeing here is that in a system where selling one’s labor power is a condition of survival for the majority, both business leaders and governments are abdicating their obligation to provide sufficient labor. Companies have secretly been openly hostile to employee growth in recent years, increasingly presenting headcount reductions as a badge of honor. These cuts are hitting entry-level workers hard. Since the site’s inception, we’ve regularly noted requests for help on the tech site Slashdot, and new computer science graduates seeking advice because they can’t get a job. The Greybeards have confirmed that although this is a serious problem, they can offer little guidance on what to do. Since the early 2010s, there have been increasing reports that technology is disrupting entry-level jobs in law, where lower-level research and drafting were important to workers learning the trade.

We believe these practices are also destructive at the individual company level. Employers have come to treat their employees as disposable, and appear to enjoy the power that comes with increased employee insecurity. But disposable workers are not loyal. Furthermore, turnover has the cost of selecting and training a replacement (which at least requires learning certain procedures and rules). However, the superior class may not care about that. Because that extra effort is put on us and falsely increases our claims of worth.

But even if it can be argued that these new norms are good for individual companies, they clearly have negative effects at a larger societal level. More and more young people become dependents of their families and states, hindering household formation and childbearing. Population growth is one of the two drivers of economic expansion, along with productivity growth. It is true that a slowdown/reversal of population growth is necessary if we are to have any hope of ending resource depletion, environmental degradation, and species loss. But how this works is that the rich at the top enrich the rich, who continue to live debauched and destructive lifestyles, offsetting potential global benefits.

One of the strange features of this modern youth incarceration is that, whereas decades ago, at least some of these disaffected youth might have taken to the streets or joined organizations (including gangs) that were not members of respectable society, the soma of mechanisms may be serving the elite by diverting energy and attention into isolation. However, cynics may point out that smartphone addiction is not only demotivating but also often causes depression, and drugging young people is another way to exploit them without making them feel responsible in the form of troublesome workers.

Before moving on to the Financial Times article, here are some excerpts that confirm the extent of the underlying factors behind high levels of youth unemployment. According to the latest official U.S. employment data for August 2025, the unemployment rate for college graduates aged 20 to 24 was 9.3%, significantly higher than the unemployment rate for those with older degrees (the unemployment rate for those aged 25 to 34 was 3.6%). The pattern of high unemployment rates for new graduates has continued since the pandemic.

Even though many young people are sitting on their own, many employers are bringing in foreign workers to replace them.

About a dozen ski resorts in Vermont are hiring nearly 1,400 workers on J-1 visas from overseas this winter.

The United States is a large country where youth unemployment is rapidly increasing.

Why not try recruiting at home? pic.twitter.com/f4FiCBxRwZ

— Barefoot Student (@BarefootStudent) November 12, 2025

And it’s not just the US.

european union #Youth #unemployment September 2025:

🇪🇸25.0%

🇸🇪24.0%

🇷🇴23.5%

🇫🇮21.5%

🇱🇺20.9%

🇪🇪20.6%

🇮🇹20.6%

🇬🇷18.5%

🇫🇷18.3%

🇵🇹18.1%

🇱🇻17.6%

🇨🇾17.2%

🇭🇷16.7%

🇸🇰16.2%

🇱🇹15.2%

🇪🇺14.8%

🇧🇬14.5%

🇭🇺14.4%

🇩🇰13.9%

🇧🇪13.8%

🇵🇱13.0%

🇮🇪12.2%

🇸🇮12.2%

🇦🇹11.9%

🇨🇿10.2%

🇲🇹10.1%

🇳🇱8.8%

🇩🇪6.7%@EU_Eurostat

— EU Social🇪🇺 (@EU_Social) November 5, 2025

Canada’s youth unemployment rate significantly underestimates the youth employment crisis. This is because young people are leaving the workforce.

Now, after importing millions of dollars to compete with them for jobs, Canada’s boomer party is asking them to hold the bag. It’s embarrassing. pic.twitter.com/c3dS7xkweX

— Richard Dias (@RichardDias_CFA) November 5, 2025

If you read the IMF Asia Outlook, youth unemployment is rising across the board, especially in South Asia and China. pic.twitter.com/MLP2aQk7kk

— Trinhnomics (@Trinhnomics) October 31, 2025

With China’s youth unemployment rate expected to exceed 20% in 2023, the government scrapped that calculation method and released new statistics in December 2023. Yet, with this “better than ever” approach, the youth unemployment rate improved from a reported 18.9% in August to just 17.7% in September.

Countries with low youth unemployment may be struggling to exit.

Italians continue to leave Italy. That is one of the reasons why youth unemployment has improved over the past decade (there are simply no young Italians unemployed). Germany remains a top destination. HT @maps_interlude pic.twitter.com/6JUirEX9hv

— Simon Kustenmacher (@simongerman600) November 1, 2025

Next, let’s move on to the Financial Times account. Although this is a UK-centered work, many of its observations apply to other countries as well. It begins with efforts that began in the UK in the 1990s to identify NEETs, as well as young people who are not in education, employment or training. A small problem is that this cohort also includes housewives, so simple data collection may be misleading. nevertheless:

The concept has rightly become a staple of international economic statistics, with studies consistently finding that NEETs risk lifelong socio-economic scarring, and are at significantly higher risk of unemployment and health problems for decades.

While these numbers are alarming enough, there are additional factors lurking beneath the surface that mean these groups are struggling more than in the past, and that reversing the trend may be more difficult.

One contributing factor is the deterioration in housing prices in many countries, which means an increasing proportion of young people are staying with their parents, which can reduce their desire to work.

Another big challenge is the role that anxiety and other mental health conditions play.

In the UK, a large proportion of socio-economically isolated young people report suffering from mental health problems that prevent them from working or looking for work. This, combined with the nuances of the UK’s welfare system, may be one reason why the UK’s long-term trend in youth unemployment is so steep. Changes in the relative proportions of unemployment and disability benefits are causing many people to transition from the former to the latter, and many are concerned that once they receive health-related benefits, they will lose them if they try to re-enter the workforce.

A further UK-specific concern is that youth employment rates are being hit by significant increases in the minimum wage for young people and policy changes that increase the costs for businesses of employing low-wage workers.

The third point highlighted to me by Louise Murphy, senior economist and young unemployed expert at the UK think tank Resolution Foundation, is that this group has been severely affected by the increased amount of time they spend alone, as smartphones and other digital technologies replace face-to-face socializing. In the United States, young people who aren’t working, studying, or raising children now spend seven hours a day completely alone compared to five to 10 years ago.

In the United States, in addition to housing costs, which are barriers to independent living, there are surprisingly high medical/insurance costs, and Medicaid has a cliff effect. Even in states with Medicaid expansion, the cutoff is typically 138 percent of the federal poverty line. And consider that in states like Alabama, singles pay just $1,014 a month, in Arkansas it’s $1,044, and in Colorado and Georgia both $994. But it’s a generous amount compared to Kentucky’s $235 or Maryland’s $350.

Therefore, the relentless march of neoliberalism is currently causing serious harm to young people who historically have had a promising future. And the dreams of feverish tech tycoons to further reduce employment levels for educated people are only just getting started (many argue that a series of large-company job cuts based on market-pleasing AI justifications went a long way toward alleviating overemployment during the pandemic). But neoliberalism, enabled by smartphones, has succeeded far beyond Thatcherite dreams of creating atomization and destroying the kind of social cohesion that in previous generations might have generated backlash and mutual aid societies, not only from homebound graduates but also from the parents who still supported them.

In other words, in the words of a grumpy friend, “If you want a happy ending, watch a Disney movie.” Other than slowing and reversing population growth in resource-intensive societies, it’s hard to find that here.