ProPublica is a nonprofit news company that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter focused on fraud across the country, and get it delivered to your inbox every week.

On May 14, the last day for new legislation in the Mississippi Legislature, a bold new bill landed on the desks of Mississippi lawmakers. The plan called for creating a voucher program to pay for students to attend private schools.

A few weeks later, in the mid-June heat, the governor urged lawmakers to support a $40 million plan that would “bear the fruits of healthy progress for 100 years long after this generation is gone.” ” he promised. He assured that support for public schools will continue. However, vouchers would “strengthen the overall educational effort” by giving children “the right to choose the educational environment they desire.”

That was in 1964.

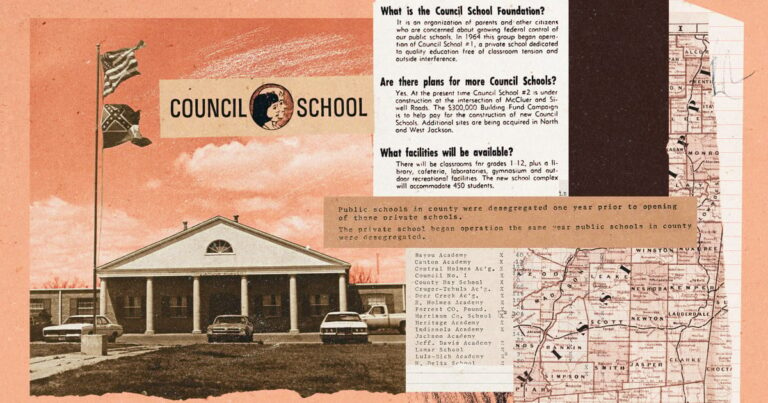

Key supporters of the movement include a group of white racists formed after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state-mandated segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Ta.

Across the South, courts in Alabama, Louisiana, Virginia and Arkansas have already rejected or restricted similar voucher plans. But Mississippi lawmakers went ahead and adopted the program anyway. For several years, the state poured money into white families desperate to send their children to newly opened private schools as black children enrolled in previously all-white public schools for the first time.

Sixty years later, ProPublica has learned that many of these private schools, known as “segregation academies,” are still operating across the South, and many once again benefit from public funding. I discovered it. Earlier this week, ProPublica reported that 39 people in North Carolina alone received vouchers worth tens of millions of dollars. Mississippi has identified 20 schools that opened as segregated academies and may have received nearly $10 million from the state’s tax credit donation program over the past six years.

At least eight of the 20 schools opened with early voucher support in the 1960s.

Steve Suits, historian and author of Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement, said that “publicly funded private schools had their origins in segregated academies.” .

Most of the private schools that receive funding from voucher-style programs that are exploding across the country are not segregated academies. However, the areas where academies operate, particularly in rural areas, often promote racial segregation within the school, which in turn fosters racial segregation throughout the community.

Even though decades have passed, most segregated academies in Mississippi are overwhelmingly white, with a much higher proportion of white students than the counties in which the schools operate, according to a federal private school study. is shown. Mississippi is the state with the highest percentage of black residents.

At 15 of the 20 academies benefiting from the tax credit program, the student body was at least 85% white as of the last census of federal private schools in the 2021-22 school year. And of the 20 locations, enrollment in five locations was more than 60 percentage points whiter than their community. Another 11 were at least 30 percentage points whiter.

In 1964, the White Citizens Council was among the groups promoting the voucher program. The racial justice organization was founded in the 1950s by Robert “Tut” Patterson in the Mississippi Delta town of Indianola. He aimed to “save schools from consolidation if possible” and “if that failed, develop a system of private schools.” our children. ”

For Patterson, it was personal. His family, including his young daughter who was starting school that fall, lived in what he called “the plantation,” which was home to 35 black families. He later told an interviewer: We actually lived with them. we loved them. We took care of them, but we didn’t want our children with them. ”

The state’s voucher program provided $185 per student to help pay for private school tuition. That’s about $1,876 in today’s dollars. The bill’s preamble states that it aims to give each child “individual freedom to choose public or private education.”

Shortly after lawmakers adopted the plan, the American Citizens Council followed up with advice on “How to Start a Private School” and “Sample Corporation Charter” with a monthly magazine. According to court records, private schools emerged primarily from public school districts that submitted court desegregation orders or voluntary desegregation plans to the federal government.

In the first four years of the voucher program, the number of new segregated academies that received public funding snowballed from two to 49. Of those schools, 48 did not admit black students. Some took in black children, but only black children.

John Giggy, a historian at the University of Alabama and director of the university’s Summersell Center for Southern Studies, has studied the birth of these private schools. These days, he says, people often “don’t understand why these isolation academies were opened.” “This was one of the most aggressive moves Southern governors took after the passage of Brown, a move that accelerated as the civil rights movement accelerated. It rippled throughout the region.”

Vouchers became important seed money as white families rushed to open academies. In the 1965-1966 school year, vouchers covered more than one-third of the total operating costs of at least 17 new academies.

One of the early adopters was Central Holmes Academy (now Central Holmes Christian School). The vouchers paid more than 78 percent of the fledgling academy’s tuition for 210 students that grade. The school’s trustees made their feelings on integration clear in a letter later cited in federal court, in which they described “other schools” as “intolerable and disgusting.”

In 1968, Mississippi lawmakers increased each voucher to $240. The following January, black Mississippi families won a federal class-action lawsuit against the state, challenging the constitutionality of the vouchers. A panel of federal judges upheld the program’s “establishment of a system of private schools operating on the basis of racial segregation as an alternative available to white students seeking to avoid desegregated public schools.” It was determined that the

The judge ruled that the program was unconstitutional. Parents could choose segregated private schools for their children, but the voucher program involved the state in that discrimination.

In a sense, it was too late. The academy was up and running.

The U.S. Department of Justice examined the academy’s finances as part of a federal lawsuit and found that “clearly, without these donations, the school would not have survived even as an educational institution.”

By then, state taxpayers had funded more than 5,000 vouchers.

For some time, seclusion academies continued to receive other forms of public assistance, including state-funded donations of textbooks, real estate deals, and public school equipment. But vouchers were dead.

And 50 years after a court struck down the early voucher program, the Mississippi Legislature found a way to restore funding to private schools.

In 2019, the state enacted the Children’s Promise Act, which provides incentives for businesses to participate in state-funded programs for private schools. This program provides businesses with a dollar-for-dollar tax credit (up to 50% of their total tax liability) for donations to certain educational charities, including private schools. This law is intended to help children who are low-income, living in foster care, or diagnosed with a chronic illness or disability.

However, the extent to which schools place emphasis on these matters is not made public. Claims about how many students are served in these categories have not been made public that states have been asked to qualify for donations. But it is clear that tax-refunded donations are flowing into segregated academies.

The Mid-South Independent School Association, founded in 1968 by a group of segregated academies, said in its latest annual report that the Mississippi tax credit is now a “significant source of funding.” . (The association’s ethical guidelines state that member schools “shall not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, color, national or ethnic origin in the administration of admissions procedures.”)

ProPublica found that segregated academies account for at least one-fifth of all schools benefiting from tax credits.

Central Holmes is one of them. The school has received $812,150 in tax credit donations since 2020. These funds are helping to improve academic programs, update technology and promote professional development, said Chris Terry, the school’s principal.

As of the last federal private school survey, Central Holmes reported that 82% of its students were white, a change from 95% white a decade ago but far from representative of the surrounding community. It was. Holmes County’s white population is barely over 15%.

Separate academies across the South receive millions of dollars from taxpayers.

Terry, who will serve as principal starting in 2022, said the school has had Asian, Hispanic and Black students “enjoying success” during that time. Among them were a black valedictorian and a homecoming queen. “To me, this demonstrates our school’s desire to move beyond the past and build a new future for our students and families,” Terry said in an email.

He added that he could not comment on the school’s origins because he was not alive at the time.

Those who were alive when it opened in 1965 expressed different visions for its future. In 1970, a black congressman representing the central Holmes district predicted that white students would return to public schools within “two or three years.” However, the chairman of Central Homes, a former councilor, opposed this. He predicted that schools would “continue to exist indefinitely.”