Eve is here. Not surprisingly, economists find it difficult to estimate the long-term economic costs of these highly destructive weather events, as they vary in type, geographic extent, and intensity. But these exercises are important in that they could influence the scale of relief efforts (assuming a future administration wiser than Team Trump) and perhaps strengthen the case for containing climate change. The article also found that improved infrastructure within a region can help cushion the effects of weather disasters.

Although this work appears to be an important addition to the growing literature, the idea that climate disasters are local speaks to a too narrow focus, including only events such as hurricanes, catastrophic floods, and perhaps wildfires. But while heatwaves are also listed, it’s not clear how they modeled the much higher cost of electricity use (for those who can afford it), potential grid failures and brownouts, and heat-related deaths.

By Helia Costa, Economist, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and John Fourie, Senior Economist, International Monetary Fund. Originally published on VoxEU

The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are increasing, but their macroeconomic impacts are still poorly understood. This column argues that because of the highly local nature of climate-related natural disasters, impacts need to be assessed at the local level, with clear consideration of trans-regional spillovers. Such an approach revealed a significant negative impact of approximately 0.3% of annual GDP in OECD countries, with approximately half of this occurring outside the affected area due to negative spillover effects.

Extreme weather events, such as catastrophic floods and prolonged heat waves, are increasing in frequency and intensity (IPCC 2021). This has further focused policymakers’ focus on economic resilience in developing and developed countries ahead of COP30. Although there is a growing consensus that these events cause severe macroeconomic losses (Krebel et al. 2025), quantifying them accurately remains difficult (Aerts et al. 2024).

For developed countries, it has become more difficult to document evidence of strong and significant adverse effects, especially in studies using cross-border data (Botzen et al. 2019, Klomp and Valckx 2014). There is growing recognition that the highly local nature of weather shocks requires studying their impacts at the local level (Goujon et al. 2024, Dell et al. 2014), and that combining detailed data across countries and event types is essential to fully understand their macroeconomic impacts.

Against this backdrop, a new study (Costa and Hooley 2025) uses regional data from more than 1,600 regions in 31 OECD countries from 2000 to 2018 to assess the economic impact of extreme weather events in developed countries. This includes how impacts propagate beyond the original event location through spillovers.

Large-scale, persistent, non-linear impacts

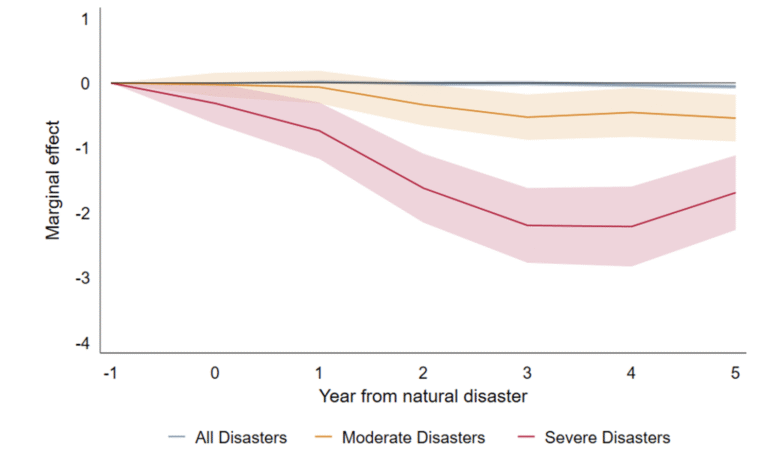

The most severe disasters reduce the GDP of regions directly affected by the disaster by up to 2.2% compared to the trend, and the loss continues at around 1.7% five years later (Figure 1). But not all disasters are equally important. The most severe disasters, defined as affecting at least 0.1% of a region’s population, cause disproportionately large production losses compared to more moderate disasters, while mild disasters have no measurable GDP impact. Such nonlinearities have also been documented by others (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014) and are probably due to capacity constraints, i.e. technical and organizational limitations that are only binding in case of major disasters (Hallegatte et al. 2007). Small shocks are absorbed. Big things can be overwhelming.

Figure 1 Change in real GDP level after major disasters (%)

Note: Lines show local forecast estimates at each post-disaster horizon for all, moderate, and severe disasters. The shaded band is the 90% confidence interval.

Source: Costa and Fourie (2025). Data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).

The labor market is an important adjustment channel. Employment declines in proportion to GDP, and affected regions experience net outward migration. Migration is an important coping mechanism for households, but it can also exacerbate regional production losses by eroding demand and depleting human capital.

Severe disasters also put downward pressure on prices. The GDP deflator will fall to about 1% below trend over the medium term. Shortage of demand overwhelms supply-side inflationary pressures from damaged capital, production disruptions, and labor market disruptions.

Because these are net effects on production and prices, they already incorporate countervailing forces such as recovery spending, insurance payments, and government aid transfers. The continued large losses indicate that while this aid is helpful, it is on average insufficient to return the economy to its pre-disaster trajectory.

Negative impact on neighboring areas

The economic damage does not end at national borders. We have identified significant negative spillover effects. Severe disasters that occur within 100 km of a region reduce GDP by an additional 0.5%. This is about a quarter of the direct impact. These spillover pathways may reflect several factors, including supply chain disruptions, reduced demand from nearby affected areas, and population displacement.

When direct impacts and spillovers are combined and aggregated across OECD countries, severe disasters in our sample reduced GDP by more than 0.3% per year on average, and spillovers accounted for about half of total losses (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average annual impact of severe disasters on OECD GDP (percentage) from 2006 to 2018

Note: Panel A shows the average annual GDP loss (2006-2018) for 31 OECD countries due to severe disasters, combining direct impacts and spillovers from disasters within 100 km. Losses are derived by applying 5-year estimated elasticities and aggregating by region. Panel B plots the distribution of annual direct and spillover effects for each country. Markers and horizontal lines indicate the mean and median, the top and bottom of the box indicate the interquartile range, and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values.

Source: Costa and Fourie (2025). Data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).

Why some regions are more resilient

The ability to withstand and recover from disasters varies widely by region. Fiscal space matters: Regions of countries with lower debt-to-GDP ratios will recover faster because governments can deploy effective post-disaster support without having to offset austerity measures that can exacerbate economic downturns (Canova and Pappa 2021). Economic diversification and workforce mobility also strengthen resilience. A diversified economy can shift activity to less affected sectors, and increased liquidity accelerates redistribution and limits persistent unemployment (Beyer and Smets 2015).

The sector patterns are also very different. After severe disasters, industrial output declines by more than twice as much as service sector output, but, not surprisingly given the industry’s dependence on fixed capital and networked supply chains, it tends to recover faster in the medium term once supply chains are restored and spending is restructured.

Policy implications

Quantifying the potential economic losses caused by natural disasters is critical for effective planning and decision-making. Our estimates show that even in developed countries there will be large, nonlinear, and persistent costs, calling for climate damage projections that explicitly incorporate the impacts of extreme events. However, this challenge is difficult, and although recent studies have begun to incorporate temperature and precipitation variability into climate damage functions, the most extreme ‘tail’ events are unlikely to be captured (Aerts et al. 2024).

The scale of this loss also highlights the urgency of adaptation efforts in developed countries, including investment in adaptive infrastructure (flood protection, water storage, resilient transport, electricity), alongside reliable post-disaster planning and deeper insurance markets (OECD 2024).

Our evidence of negative spillovers further sends a clear policy message that climate adaptation cannot be narrowly focused on sites of potential danger. Given that about half of the economic damage from natural disasters occurs in areas not directly affected, such a strategy leaves significant costs unresolved.

These represent several complementary priorities.

Infrastructure resilience beyond the danger zone. Where supply chain disruptions cause negative economic impacts, investments in resilient infrastructure must consider network effects. Cross-border coordination mechanisms. Effective disaster response requires shared early warning systems, joint disaster response and recovery planning, and, in some cases, coordinated financial support. Reduce labor market friction and redistribute. Promoting more flexible labor market institutions and targeted upskilling efforts will help displaced workers move quickly into new employment in less affected sectors and regions.

In parallel with broader adaptation efforts, strengthening resilience to spillover effects is critical to mitigating the economic and social impacts of extreme weather events and preventing disasters from widening regional inequalities.

See original post for reference