I was in Park City, Utah from June 1st to June 13th. I participated in the Institute of Legal Education, run by the Scalia Law School’s Legal & Economics Center. This is a two-week crash course in American law and I share sub-insights on future posts (if you’re an economics expert, I highly recommend this program).

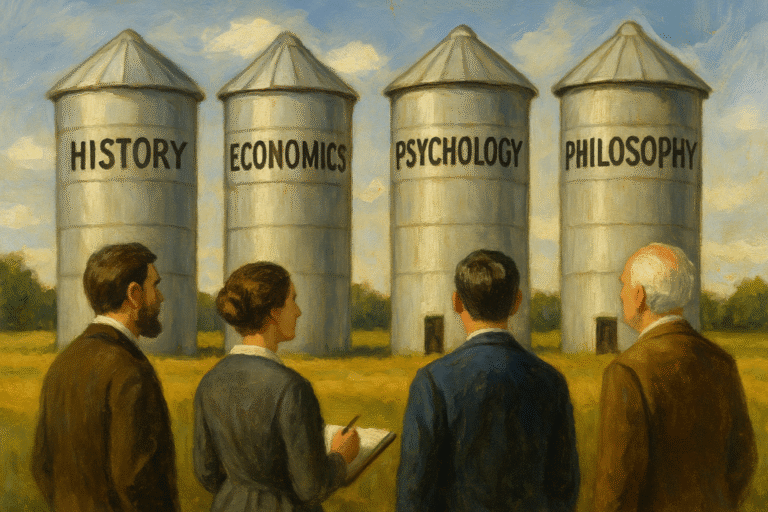

One of the big takeaways I’ve studied is how to break down disciplinary barriers. Public American discourse has a developing tendency to separate things into clear fields. X is a political issue and a public health issue. So you should get this twice in the last five years. Firstly, we are “stay in your lane” every time economists give us opinions, as governments have been implementing seemingly random policies during the Covid pandemic. But of course, economics permeates every aspect of our lives. It is a study of how people make constrained choices. Changing constraints, changing incentives, economics has a lot to do with that problem. Certainly, if public health officials listened more to economists (and other fields), they could have avoided the failure of the cascade that characterizes America’s response to Covid. Recently, economists have been said that our criticism of Trump’s trade policy is irrelevant because it is a “political” issue.

However, trying to separate the problem into clear silos leads to poor thinking. Economics (and other disciplines) have insight into real-world issues beyond what people argue. Yes, economics sometimes spoke about the conditions of the pandemic SP because they knew that price control would lead to a lack of. In a pandemic pandemic by intimate contact with each other, people have more contact points, create more disease vectors, and increase the premise of SP. Economics also had insight into how more needed products were produced.

To bring this back to law and economics, one of the things that make up me during a meeting is how much law and economics have to say to each other. I don’t make any sense in the sense of Richard Posner, who argued that economics should make law more efficient. Rather, I mean that bow law and economics study social order. We just eat it from a different angle. To be clear, by “laws” I simply do not mean laws or government-made rules (though they are part of the social order). Rather, I call “laws” a set of rules created by the juvenile government, created by the juvenile government that governs our daily lives. Economics talks a lot about emergency situations and the persistence of these emergency rules. Economics talks a lot about the incentives facing legal actors (judgments, juices, expert witnesses, etc.). And likewise, the law has a lot to say about how people negotiate and exchange.

Adam Smith makes famous that division of labor reveals how it can increase our production capacity and lead to more discoveries. But he also warns against extending this logic too far. If too specialized, it can lead to “nourishment of his mind” and “being foolish and ignorant as human creation is positive” (wealth of wealth pages 781-782). Siling is just that. Yes, you need to specialize. However, we are not so ignorant of the world around us to reject insights from other fields. To that end, I will share sub-insights from the law in the next few posts.