Historian Robert Paxton spent January 6, 2021 glued to the television. From his Upper Manhattan apartment, Paxton watched as rioters marched toward the Capitol, climbed over security barriers and entered the building as police cordoned off the building. Many in the crowd wore red MAGA baseball caps, while others wore bright orange beanies identifying them as members of the far-right extremist group Proud Boys. Some had even more spectacular costumes. Who is this character in camouflage and antlers, he wondered? “I was completely transfixed by it,” Paxton told me when I met him this summer at his home in the Hudson Valley. “I never imagined that something like this would come true.”

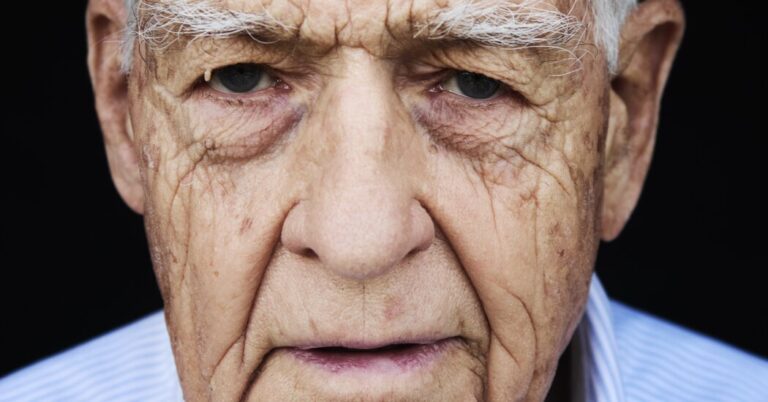

Paxton, 92, is one of America’s leading experts on fascism and perhaps the greatest living American scholar of mid-20th century European history. His 1972 book, Vichy France: The Old Guard and the New Order, 1940-1944, describes the domestic politics that led France to collaborate with its Nazi occupiers and forced France to take full account of its wartime past. tracked the forces.

The study took on new relevance in 2016, when Donald Trump was closing in on winning the Republican nomination and articles comparing American politics to 1930s European politics began to proliferate in the American press. It looked like something. Michiko Kakutani, then chief book critic for the New York Times, was one of the first to set this tone. She turned her review of Hitler’s new biography into a thinly veiled fable about “clowns” and “dunderheads” – selfish, pathological liars with a talent for reading and exploiting weaknesses. Conservative commentator Robert Kagan wrote in the Washington Post: Not jackboots or salutes, but “television scammers.”

In a French newspaper column republished in Harper’s Magazine in early 2017, Paxton appealed for restraint. “We should hesitate before applying this most harmful label,” he warned. Paxton said Trump’s “scowl” and “protruding jaw” reminded him of “Mussolini’s theater of the absurd,” and that Trump blames “foreigners and despised minorities” for “national decline.” I admitted that I liked it. fascism. But the word had been used so bluntly that “everyone you hate is a fascist,” he said, and the word had lost its illuminating power. Despite superficial similarities, there were too many differences. The first fascists, he writes, “promised to overcome the weakness and decline of the state by strengthening it and subordinating the interests of the individual to the interests of the community.” In contrast, Trump and his cronies wanted to “subordinate the interests of communities to the interests of individuals, at least the interests of wealthy individuals.”

Since President Trump took office, a slew of articles, essays, and books have embraced the fascism analogy as useful and necessary, or criticized it as misleading and unhelpful. The debate was so relentless, especially on social media, that it became known to historians as the fascism debate. Mr. Paxton, who at this point had been retired from Columbia University for more than 10 years and had been a history professor there for more than 30 years, did not pay much attention to the online discussions, let alone participate in them. Ta.

Please wait while we confirm your access. If you’re in reader mode, exit and log into your Times account or subscribe to all Times.

Please wait while we confirm your access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want to know all about The Times? Subscribe.