Eve is here. This post provides some useful analysis of U.S. programs that encourage or require the purchase of domestic products by the federal government. Consider the impact on employment. But because this policy is not as beneficial without industrial policy, it ignores common questions such as whether buying more U.S. goods is too focused on capabilities and competitiveness. .

Needless to say, this article highlights the problems with President Trump’s DOGE program. Logically, a fixed-cost initiative should require U.S. government agencies to purchase the lowest-cost products. But that conflicts with his orders to punish strategic competitors, particularly China, by reducing trade surpluses with them.

Written by Matilde Bombardini, Andres Gonzalez-Lilla, Binjin, and Lee Chiara Motta. Originally published on VoxEU

“Buy domestic” clauses act as non-tariff barriers to trade and are often defended as job creation and industrial policy tools. This column examines the costs and benefits of current and anticipated provisions under the Buy American Act of 1933 that prevent federal agencies from purchasing “foreign” goods. Enacted during the Great Depression, this law continues to guide federal procurement in the United States and has been revised under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Our findings show that while these policies have the potential to increase domestic employment, they are accompanied by increased welfare costs.

The continuing policy debate over rising protectionism and tightening trade restrictions has sparked a wide-ranging dialogue among economists. Although recent studies have focused attention on the costs associated with tariffs (Fajgelbaum et al. 2020), evidence on the impact of non-tariff barriers remains limited (Conconi et al. 2016, Kinzius et al. 2019). . One measure is the adoption of “buy domestic” provisions in public procurement, requiring goods acquired by the federal government to meet local procurement or manufacturing requirements.

These provisions act as barriers to the importation of goods and create welfare costs by reducing the import share compared to free trade conditions. When buy-national provisions require governments to purchase expensive domestic products, the resulting costs are borne by taxpayers. But proponents argue that sourcing goods domestically helps foster job creation and retention, raising questions about what the ultimate welfare costs of these policies will be. It is occurring.

Bombardini et al. (2024) address these questions by examining one of the oldest and most prominent examples of domestic content restrictions in public procurement, the Buy American Act of 1933 (BAA) . The BAA set a precedent by requiring federal agencies to prioritize “domestic finished products” and “domestic construction materials” for contracts awarded in the United States that exceed a small purchase threshold, typically set at $3,500. Two key elements of the BAA are that, unless certain exemptions are met, (1) goods purchased by the U.S. federal government must be manufactured in the United States; and (2) at least 50% of the cost of components must be made in the United States. The requirement is that it must be manufactured domestically. spent on U.S.-produced inputs.

Created during the Great Depression, the BAA has become a source of renewed debate for several reasons. First, the context of globalization has changed significantly since its inception, characterized by a significant increase in trade volumes and changes in trade composition. Currently, two-thirds of world trade consists of intermediate goods (Johnson and Noguera 2012, Antràs and Chor 2022), which influences the impact of the BAA. Additionally, the BAA laid the groundwork for a variety of domestic content mandates, including the Federal Highway Administration’s “Buy America” policy and the “Build America, Buy America” provisions of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021. It will be subject to reform under both the Trump and Biden administrations. The most significant changes in nearly 70 years are set to make the BAA even more restrictive by 2029. This change introduces one of our counterfactuals.

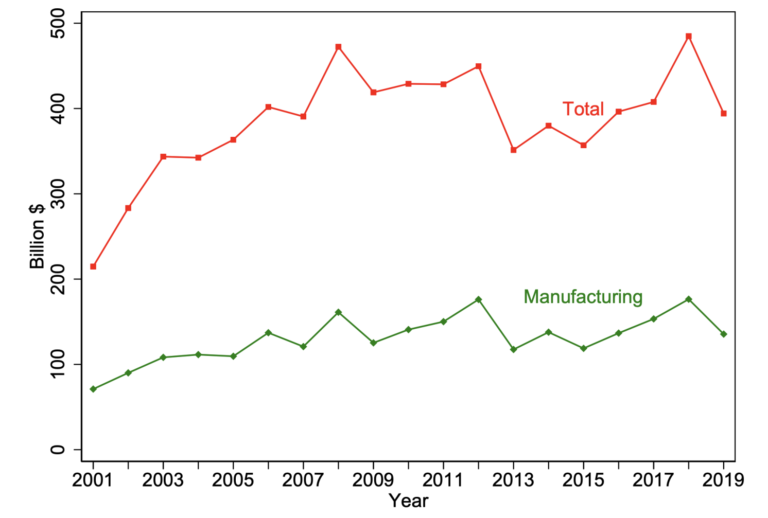

Our analysis leverages microdata from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS), which covers all federal procurement contracts from 2001 to 2019. This comprehensive dataset provides insight into contract amounts, product/service department codes, and geographic location of both purchases. agencies and production companies (including domestic or international positions); Figure 1 shows annual procurement spending trends. The red line represents total spending across all categories, while the green line focuses on manufacturing contracts. From 2001 to 2008, procurement spending doubled and then stabilized at about $400 billion annually. Manufacturing accounts for about a third of this spending and includes a variety of sectors.

Figure 1 Federal procurement spending, total and manufacturing only, 2021-2019

The main advantage of these detailed data is that they reveal, by industry, the proportion of government consumption supplied by foreign firms and can be compared with the import penetration of private consumption. This comparison highlights how governments are more constrained than the private sector in their ability to procure supplies. Figure 2 shows that government import penetration by industry (NAICS6) is significantly lower than the aggregate value. Most industries are below the benchmark values of Hufbauer and Jung (2020) and Mulabdic and Rotunno (2022), which are calculated using international input-output tables that do not distinguish between import usage by final consumer (government vs. household). It is located on the left side.

Figure 2 Total import penetration rate and government import penetration rate at NAICS6 level (manufacturing industry only)

A second advantage of our data is that it allows us to map the geographic distribution of government purchases. Figure 3 shows the large spatial variation in procurement shocks across U.S. commuting areas. We use shift-share measures to highlight the significant impact that procurement spending has on the labor market. Over five years, government spending on goods produced within commuting distance would increase by $2,947 per worker (one standard deviation), boosting manufacturing. Employment as a percentage of the working age population decreased by 0.47 percentage points.

Figure 3 Ratio of federal procurement spending to total shipments at the commuting area level

To assess the welfare costs and benefits of BAA (including employment and industrial policy considerations), we extend the quantitative model of Caliendo and Parro (2015) to include characteristics associated with BAA. Consumer welfare comes from both private market goods (as in traditional models) and public goods produced in different regions of the United States and funded by the government through labor taxes (such as national defense and national parks). depends on consumption. However, due to the provisions of the BAA, companies producing for the government face higher trade barriers and production costs than those in the private market, affecting both final and intermediate goods. We consider sector-specific external economies of scale where productivity is influenced by sector-wide employment, including labor supply decisions for workers across sectors and underemployment. Within this framework, welfare could be improved by tightening government policies for sectors with strong economies of scale.

By combining our model with a comprehensive trade matrix that includes both government and private consumption and final and intermediate goods, we quantify for the first time the effective trade barriers imposed by the BAA. Our findings show that the BAA’s restrictions on final imports are significant, leading to a 96% reduction in government imports for the average manufacturing industry. Although the current wedge on intermediate inputs is not yet restrictive, future changes are expected to extend its impact to several more sectors.

Based on these results, we use our model to apply exact Hutt algebra (Dekle et al. 2007) to estimate the potential impact of announced and possible future changes to the BAA. We will conduct a series of counterfactual exercises by investigating. First, we simulate the impact of lifting BAA-related import restrictions, effectively creating a scenario for free trade in the government sector. This change would result in an estimated loss of approximately 100,000 manufacturing jobs and an equivalent change cost of $132,100 to $137,700 per job. However, we recognize that completely removing these provisions is unrealistic for industries related to national security. To address this dilemma, we use specific provisions of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to identify sectors of national security concern. Incorporating this consideration only slightly reduces the magnitude of the estimates.

Second, under policies introduced by Presidents Trump and Biden, restrictions on foreign intermediate inputs will be significantly tightened, increasing the required minimum share of U.S.-produced components to 50% by 2029. It is scheduled to be raised from 75% to 75%. Our model predicts that this strengthening will increase domestic imports. Manufacturing added 41,300 jobs. However, this comes with significant benefit costs, estimated at between $154,000 and $237,800 per job. Therefore, the “increased cost of Buying American” stems from two main factors. First, newly protected sectors that compete with foreign intermediate inputs generally have lower labor shares compared to sectors that are protected by final goods restrictions. Second, the regions most affected by rising input costs are those with high levels of government procurement activity, resulting in higher procurement costs for public goods.

Regarding external economies of scale, two important findings emerge. First, when we run the counterfactuals with and without external economies of scale, we find that most of our previous results remain largely unchanged. This indicates that the current stringency of the BAA is not consistent with the strength of external economies of scale. In other words, the BAA provisions do not effectively target the areas where industrial policy is likely to provide the greatest benefits. Inspired by this insight, we conducted an exercise to reallocate the BAA wedge across sectors, fully aligned with the strength of economies of scale. This adjustment resulted in a modest increase in welfare of $3.69 per person and a decrease in employment of 13,700 jobs.

Taken together, our findings show that while these policies can promote domestic employment, they also come with increased benefit costs and raise questions about the economic impact of tightening domestic content requirements in government procurement. This suggests that

See original post for reference