ProPublica is a nonprofit news company that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter focused on fraud across the country, and get it delivered to your inbox every week.

A series of suspicious deaths. Two cases of infanticide that were almost recognized as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Opioid overdose death rates are mysteriously low. They are an attempt by those in power to change the state’s death investigation system, which for decades has relied on elected county coroners with virtually no state support or oversight. This is one of the red flags that we have pointed out.

Lawmakers have come close to enacting reforms several times. However, all attempts ended in failure. In many cases, the reason is simple: “No one wants to spend money on a death,” current and former coroners and state experts have told ProPublica in recent months.

But that leaves Idaho with a system in which one coroner can choose not to follow national standards, while coroners in neighboring counties follow them.

Calls to reform the system in Idaho have surfaced roughly every decade since at least the 1950s. Some of the initial pleas for change came from local doctors and state health officials concerned about Idaho’s refusal to modernize its approach to investigating deaths.

Calls to reform Idaho’s troubled coroner’s system have gone unanswered for decades

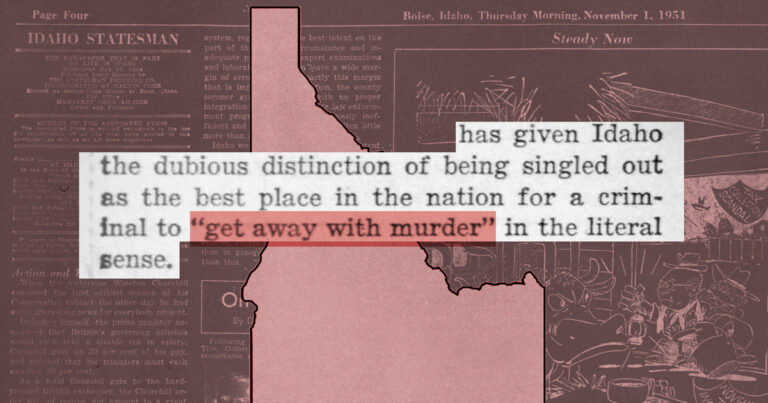

November 1951

The Idaho Statesman highlighted an article in a national magazine that said Idaho was “the best place in the nation for criminals to literally ‘get away with murder.'” That’s because Idaho “exemplifies how an outdated county coroner system contributes to frequent miscarriages,” he said. justice. “

Credit: Idaho Statesman. Highlighted by ProPublica.

March 1959

A doctor who served as coroner for Idaho’s largest county has resigned, citing “outdated and woefully inadequate” state laws. He said lawmakers that year refused to introduce a bill that would be “a middle ground between the gross deficiencies of the current law and the central state medical examiner system.”

September 1965

Dr. T.O. Carver, the state health officer at the time, told the Associated Press, “If someone wanted to commit murder without being detected, I think Idaho is a good place to do it.” Ta. Carver praised Oregon’s coroner system and said changing to a similar system in Idaho would be more expensive but would provide evidence and truth.

Credit: Sandpoint News-Bulletin via Bonner County Daily Bee. Highlighted by ProPublica.

October 1965

Idaho’s director of vital records has sounded the alarm about coroner qualifications, the state’s autopsy rate and “suspicious” death investigations. He said that in Idaho, coroners handle 600 to 700 deaths each year, and less than 10% are autopsied.

Autumn of 1976

A pathologist at a rural Idaho hospital has called for the state’s “antiquated” medical examiner system to be replaced by the Office of the Medical Examiner. “Idaho is one of the states where you can commit murder and be hard to find,” he said, according to news archives. “With a little bit of intelligence and care, under our county’s current coroner system, no one would ever know it happened.”

Credit: Times News. Highlighted by ProPublica.

March 1997

Following a series of suspicious deaths, an Idaho politician once again urged reform in an editorial, writing, “Idaho must recognize the limitations of our elected coroner system.” said the people. “Idaho residents need protection. We need coroners, pathologists and medical examiners who can work with law enforcement to catch criminals.

Credit: Idaho Statesman. Highlighted by ProPublica.

December 1998

The Post-Register newspaper in eastern Idaho did a series on child deaths, including two cases of infanticide that were most likely caused by SIDS, but autopsies were found to be lacking. Over the next five years, lawmakers considered a coroner reform bill but failed to pass it. “It didn’t work in the late 20th century, and it won’t work in the 21st century,” one county prosecutor told the newspaper.

January 2006

Ten years after her son’s death was ruled a suicide without an autopsy, a Boise woman who became his attorney told the Idaho Statesman, “Lawmakers will reconsider the law governing Idaho’s coroner system.” There is a need,” he wrote.

February 2019

The former state senator, family physician, and county coroner wrote on his blog that opioid overdose deaths “are likely underreported at a significant rate” in Idaho, in part because He said this is due to the failure of medical examiners to detect and report opioid overdoses. “Ever since I served as Latah County Coroner for 15 years, I have questioned the wisdom of the county coroner system in Idaho,” Dan Schmidt wrote. “County coroners, are you satisfied with the system for investigating your deaths? Are you doing a good job? Is there a way to do this better?”

Data reporter Ellis Simani contributed to data analysis.