Propublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates power abuse. Sign up and receive the biggest story as soon as it’s published.

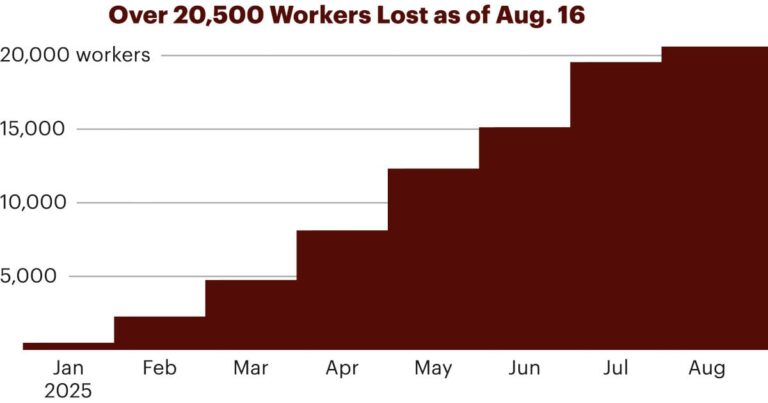

The Trump administration refused to reveal how many workers have left federal health agencies amid a massive purge. Without official numbers, Propublica relied on the federal employee directory to quantify the impact.

Several news outlets, including Propublica, use this directory to show those who are joining the federal government and leaving, finding political appointments and identifying members of government efficiency. According to documents from multiple former and current employee and health agencies, HHS employee directory helps workers find and authenticate their colleagues. HHS did not respond to ProPublica’s questions about why they wouldn’t share data on employee reductions.

To understand the changes in staffing over time, Propublica has regularly archived the HHS directory, even before President Donald Trump took office. Unlike the often outdated and incomplete official government workers datasets, directory data provides more photos of people employed by the nation’s largest health agencies and not employed.

How deeply Trump cuts federal health agencies

The HHS Directory covers staff in the department’s main office and more than 12 health agencies and agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.

The directory provides workers’ names, email addresses, agents, offices and positions. Some employees are flagged as “non-governmental,” indicating that they may be working on a contract or have a different temporary status.

The official HHS employment number suggests that its workforce is around 82,000 employees, but the directory contained around 140,000 entries. The differences are explained by non-governmental workers, such as contractors, fellows, interns, and guest researchers. The approximately 30,000 records in the directory were explicitly marked as non-governmental, but this label was far from comprehensive. We found hundreds of workers with titles that suggest they are contractors but were unable to flag them as non-government.

Although these workers were not directly employed as civil servants by the government, we included them in our analysis, especially in research-heavy institutions such as the NIH, FDA, and CDC, as they are important for the operation of government agencies. We excluded directory entries tied to group mailboxes and meeting rooms rather than interns, students, volunteers, and individuals.

To analyze sales, we tracked the worker’s email address when it first appeared and last appeared. When our email address disappeared we marked it as a departure. When something new came on, we marked it as an employment. To quantify labor reductions, we counted the number of entries that were displayed in the directory before January 25th and disappeared after that date. We chose it on January 25th, taking into account the delays observed in directory updates. The start of the analysis days after Trump was sworn in should rule out most political appointees who left our analysis at the end of the Biden administration, but political appointees may have been removed from the directory after this date. The analysis includes departures through August 16th.

Our analysis aims to understand workforce reductions, but not all departures are layoffs. The worker may have left for other reasons, such as resignation, resignation, acquisitions, contract cuts, etc.

To test the accuracy of the directory, we used LinkedIn, other open source records and interviews to check employment status. Although no latest published profiles were found that matched all the people’s directories we searched, we were able to check the employment status of dozens of current and former workers.

Several well-known deviations allowed us to test our methodology: Dr Vinai Prasad, appointed to lead the FDA’s Biological Evaluation and Research Centre in May, left the agency in July and resumed his role in August. Directory data accurately reflects each of these employment changes.

They also wanted to understand the role of lost workers and how their departures would affect their institutions. For this reason, they relied on the “organization” field in the directory, allowing employees to use the Public Organization Chart to link to a specific office within the HHS. In large institutions, this field has proven invaluable to understanding the exact division in which the loss occurred.

Because job titles in the directory were inconsistent, we used a local large language model classifier to assign each title to one of four major groups: science/health, regulator/compliance, technology/IT, etc. Job titles for each category were manually reviewed and former LinkedIn employees were examined to determine the employment status and the nature of the work carried out. The total for the NIH is because 78% of the entries there do not list roles. We relied on recently listed roles of workers.

The Employee Directory is the best data you can access, but it’s not without restrictions.

Our understanding is that each record represents an individual worker. Analysis may be counted twice because they were seen by two institutions or because they had multiple email addresses. Reviews of these records suggest that these types of overlap are unusual.

Our strict review found some instances where the directory is not up to date. We excluded the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services from the analysis because the directory did not receive regular updates. We also excluded Indian health services due to an unusually high churn rate.

You can find it in your search, but you’re missing detailed records or you’re not counting around 2,500 entries that don’t list emails.

Sophie Chou provided a data report.