Eve, here. The Biden-era practice of tolerating large increases in illegal immigration, which critics saw as unduly lenient on those who began the process of regularizing their status, was one of the issues that propelled Trump into office. But voters are now flocking to see the brutal methods the regime is using to crack down. One development that has not received as much attention as might be expected is the plan currently under consideration to significantly restrict asylum applications and the treatment of applicants.

The article below describes how the administration plans to push asylum seekers who come to the United States to other countries, similar to how Israel has repeatedly tried to expel Palestinians from Gaza and get Egypt, Jordan, and other countries to agree to take them in. This analogy is not accurate because Palestinians have the right to stay in Gaza…but not according to Zionists. But Team Trump is not seeking to ban asylum seekers from entering the country to prevent economic immigrants from entering the country under false pretenses, but because, as they have repeatedly made clear, they do not like brown and black people.

A particularly troubling factor is that the government wants to get asylum seekers out of the country as quickly as possible, which includes having their cases heard in states that have agreed to accept them, like Uganda, rather than in the United States. Everyone in the continental United States has due process rights under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. I don’t see how that can be outsourced. But one may wonder how long it will take before a significant court challenge is filed.

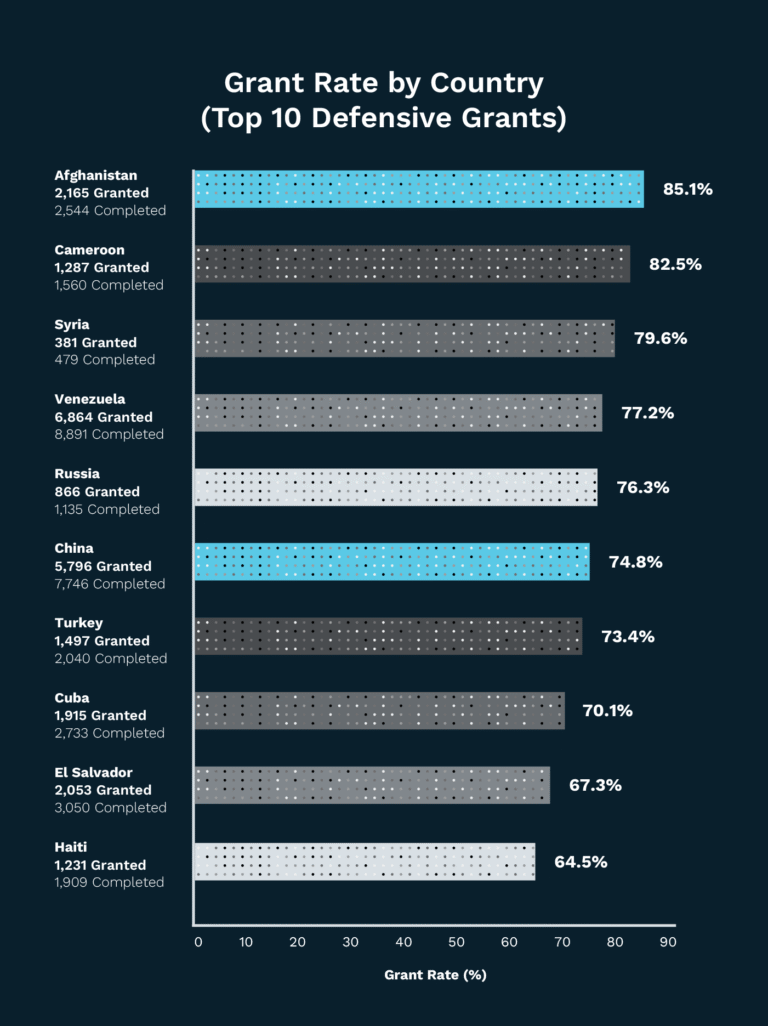

A quick search did not reveal which countries are the largest source of asylum seekers. However, the number of successful candidates has increased rapidly in recent years, according to DocketWise.

2022: 39,023 people

2023: 54,659 people

2024: 100,394

The countries of origin with the highest success rates for applicants are:

Note the overlap between that list and the countries whose citizens were eligible for Temporary Protected Status. Knowledgeable readers please speak up. But I believe some (many?) of the TPS programs were in the asylum application queue.

However, the Department of Homeland Security plans to end the TPS program for Burma (Myanmar), Ethiopia, Haiti, South Sudan, and Venezuela.

Well, here’s the latest information regarding this eviction program.

Written by Gwynne Horgan. First published on THE CITY on December 18, 2025

Father Fabian Arias comforts a woman as she leaves immigration court after being told the government intends to deport her to Uganda or Honduras (she has never been to either), Dec. 18, 2025. Credit: Gwynne Hogan/THE CITY

Homeland Security lawyers in New York immigration court are moving to close asylum cases all together, arguing that people in deportation proceedings do not have the right to seek asylum in the United States because they are eligible for asylum in Honduras, Ecuador and Uganda, three countries with which the United States has recent agreements.

Rumors of new Trump administration tactics have been circulating among the city’s immigration lawyers in recent weeks, as they are unfolding inside San Francisco’s immigration courts, according to local media. Inside New York City’s immigration courts, a novel strategy has taken off in earnest over the past two weeks, observers tell THE CITY. Hellgate earlier reported on new tactics by the Trump administration that could set the stage for the possibility of large-scale removals of third countries in the coming months.

Inside Immigration Judge Tiesha Peele’s courtroom Thursday morning, the city witnessed one Department of Homeland attorney filing a motion to “expire” asylum applications. Requests for “advancement” of asylum applications are an attempt to destroy a person’s asylum claim, leaving them vulnerable to deportation to a country they have never even entered, rather than their country of origin.

A Trump administration lawyer said, “The department is moving toward ending the defendant’s asylum application as soon as possible.” “The defendant is subject to three cooperation agreements: Ecuador, Honduras and Uganda,” he continued. “As such, the defendants are prohibited from seeking asylum in the United States.”

Peel had until Jan. 22 to appear in court and respond to the motion in writing, then set another court date for early February, where she will issue her sentence.

“Do you understand?” Justice Peel asked an Ecuadorian woman sitting in front of him who had been told she would have to apply for asylum in Uganda or Honduras. “What that means is the government is saying you don’t qualify for asylum here.”

“Yes,” the woman answered and began crying as soon as she walked out the courtroom door. “It’s very unfair,” the woman said in Spanish, asking to be identified only by her first name, Narcisa.

Another immigrant named Darlene showed up soon after, in tears. “I’m scared,” the 33-year-old said in Spanish, adding: “This is my first time in court.”

Benjamin Remy, an immigration attorney with the New York Legal Assistance Group, tried to comfort the women with information on how to respond in writing.

“This is not a deportation order,” he told them in Spanish. “You have a chance to respond.”

It’s not yet clear whether the Department of Homeland Security intends to push for early termination across the board or target specific groups of asylum seekers.

In a written statement sent to the city, DHS said it is “working to remove illegal aliens from the country as quickly as possible and ensure that they receive all legal proceedings, including a hearing before an immigration judge.”

“The Asylum Cooperation Agreement is a legal bilateral agreement that allows illegal aliens seeking asylum in the United States to seek protection in another country that agrees to fairly adjudicate their claims,” the statement reads. “DHS is using all available legal tools to address backlogs and abuses in the refugee system.”

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for the Trump administration to strengthen expulsions from third countries by blocking lower court orders requiring advance written warnings and giving those countries an opportunity to defend against expulsions, but so far the practice has not been used on a large scale.

Earlier this month, The City reported that from the beginning of the year through mid-October, only 62 people had been deported from New York state to a country other than their country of origin. This number is expected to increase further in the coming months.

From now on, people will need to submit written claims to the court in order to keep their asylum claims alive. But no one knows exactly what to say in a motion to persuade an immigration judge to keep their claims open. Even a knowledgeable immigration attorney can help, especially if you’re a recent immigrant who doesn’t speak English or can’t afford a lawyer, like many people in deportation proceedings.

“We don’t have precedent,” Remy said. “We have nothing but the statute.”

The Board of Immigration Appeals, which sets precedent for national immigration courts, ruled in a similar case in October that an immigration judge should grant a motion to grant asylum unless the person can “establish a preponderance of the evidence that the person is likely to be persecuted because of their protected status” in a third country.

Remy called the Trump administration’s latest tactic a “genocide” and said it’s worse than masked federal agents roaming the hallways of immigration court and arresting people at random.

At least at the time, Remy said, “Theoretically, you still have a chance to win. You could get a final hearing, you could be granted asylum. We’ve just seen asylum completely terminated.”

The jury is still out on how an immigration judge will rule on a motion to halt an asylum application early. The impact of these claims on people’s asylum cases will become clearer in the coming weeks, as most judges have between 10 and 30 days to respond in writing before ruling on the claims.

The move toward early asylum claims is the latest shake-up for U.S. immigration courts, part of the executive branch under the Justice Department, which have come under enormous pressure from the Trump administration, including a spate of firings of tenured judges in New York City and across the country, especially those with the highest asylum grant rates.

Volunteer court monitors shuffled between courtrooms Thursday morning, comforting people and speaking to the city in hushed voices in the hallways, trying to explain what steps to take.

“I can’t tell you how many people ask me, ‘Where is Uganda?'” said one court observer, who declined to give his full name.

“I’ve never felt so bad here,” added another man, also anonymous.