Until recently, nuclear proliferation has been treated primarily as a problem of rogue states, revisionist regimes, or localized regional instability. The prevailing belief was that restraint would provide guarantees of security, legal protection, and predictable international behavior. That assumption no longer holds. Systematic violations of legal and institutional limits on the use of force by the United States are beginning to reshape global security incentives. As U.S. aggression becomes more common, legally chaotic, and increasingly divorced from diplomatic norms, nuclear weapons are reaffirming their status as the only reliable deterrent to coercion by superior military force.

signal transmitted

Recent international actions by the United States send a clear, globally legible message: international law is voluntary, treaties are conditional, and security is political, not institutional. Threats of covert action, paramilitary force, and unilateral military intervention have become routine policy tools rather than exceptional measures. When U.S. officials openly assert unwavering authority to attack other countries and seize their resources, the lessons absorbed abroad are unmistakable. National sovereignty cannot be protected by rules and norms that those in power openly ignore. For states with sufficient resources and technological capabilities, this logic points directly to resorting to nuclear deterrence.

Why do nuclear weapons reassert their logic?

Nuclear weapons have always served primarily as a regime survival tool rather than a useful battlefield tool. Deterrence regains the upper hand because treaty compliance cannot provide protection and diplomatic coordination cannot guarantee restraint. Nuclear weapons capabilities provide a uniquely efficient means of deterring both superpowers and regional adversaries. Even a small number of launchable, rudimentary nuclear weapons would exponentially increase the risks faced by potential attackers and alter strategic calculus in ways that cannot be replicated by conventional forces within reach. Today’s proliferation pressures reflect defensive rationality under weakened international norms rather than ideological ambitions or militaristic zeal.

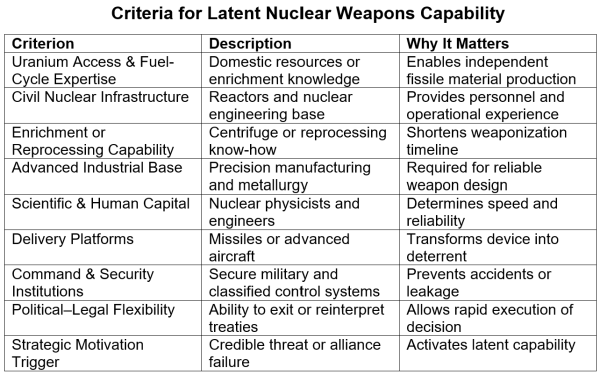

What potential nuclear capabilities mean

Many countries already possess potential nuclear capabilities and could quickly cross the nuclear threshold if given political approval. The incubation period reflects the possession of human capital, financial resources, industrial base, and technical expertise necessary to develop and manufacture nuclear weapons. In such cases, the main constraint is political rather than practical feasibility. As trust in international norms erodes, so do their restraints, compressing timelines from decades to years and even months in crisis situations.

Evaluating threshold conditions

Iran

Iran is a particularly clear example of how compliance does not ensure security. Despite years of restraint, intrusive inspections, and formal compliance with international agreements, compliance has failed to prevent the escalation of sanctions or protect Iran from covert sabotage, cyber operations, or persistent military threats. From Tehran’s perspective, compliance arguably increased vulnerability by exposing constraints without providing mutual restraint. Iran is already close to its technological limits, and the remaining barriers to weaponization are more political than technological. As trust in reciprocity erodes, nuclear capabilities are increasingly valued not as a bargaining tool but as a necessary guarantee for regime survival.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s nuclear calculations reflect strategic hedging rather than ideological aspirations. The Saudis have explicitly linked their nuclear posture to Iran’s trajectory, facing the limits of externally provided security that is both visible and transactional and revocable. Recent experience highlights that coordination does not guarantee automatic protection or durable efforts. In a system where alliance guarantees appear contingent and legal constraints on force weaken, sovereign nuclear deterrence emerges as an insurance policy against abandonment rather than an aspiration to regional dominance. Saudi Arabia has long been suspected of pursuing some type of marginal nuclear capability through its relationship with Pakistan. That is, funding past nuclear programs and maintaining an understanding of contingent deterrence that could be activated by extremists. Although there is no public evidence that Riyadh possesses nuclear weapons or completed blueprints, the existence of such arrangements highlights how countries are adapting to weakened non-proliferation norms without going beyond formal standards.

turkey

Turkey occupies an increasingly precarious position as a NATO member state possessing nuclear weapons without sovereign control while pursuing greater strategic autonomy. The Turkish government has openly questioned the fairness of the existing nuclear order and has invested heavily in advanced industrial, aerospace, and missile capabilities. As the alliance becomes less cohesive and the selective application of international law becomes more evident, Turkey’s motivation to secure an independent deterrent power increases. This pressure stems not from expansionist ambitions but from uncertainty about whether alliance-based protection can be relied upon in times of acute crisis. Turkey also faces dual potential threats from nuclear-armed Russia and Israel to the north and south.

South Korea

South Korea represents one of the most compressed proliferation schedules in the international system. Facing a nuclear-armed adversary and with advanced industrial and scientific capabilities, South Korea has long relied on extended deterrence to justify restraint. However, extended deterrence relies on predictable political commitment by the United States. As these commitments appear increasingly unstable and subject to domestic political fluctuations, nuclear latency periods serve as a reasonable guarantee mechanism against strategic abandonment. Although South Korea faces a much weaker northern enemy, it has still managed to defy the United States with its nuclear forces. The lesson for South Korea is clear. This means that the United States only respects military power.

Japan

Japan is one of the most important detention cases in world politics. With its extensive civilian nuclear infrastructure, advanced fuel cycle capabilities, and extraordinary technological sophistication, Japan’s nuclear-free status depends almost entirely on trust: faith in legal norms, predictability of alliances, and escalation control. As these assumptions weaken due to regional militarization and declining faith in rules-based restraint, the logic of permanent abstention becomes increasingly strained. Japan’s reconsideration of its nuclear posture would signal a major failure of the postwar Asian security architecture. Japan’s neighbors have long memories of the damage inflicted by Imperial Japan, and a nuclear-armed Japan would throw regional relations into dangerous turmoil.

Brazil

Brazil highlights the fragility of norm-based restraint in situations of asymmetric coercion. With a longstanding commitment to multilateralism and nonproliferation, Brazil maintains nuclear fuel cycle expertise and a sophisticated industrial base that enables nuclear energy and naval nuclear propulsion programs. As international law appears selectively binding and increasingly capable of overriding restraint, unilateral compliance begins to resemble strategic exposure rather than principled leadership. The Brazilian case highlights that once reciprocity is seen as broken, proliferation pressures can extend to countries that have historically emphasized norms. U.S. belligerent actions in Latin America will further intensify this pressure.

Germany

Germany is the most obvious threshold case. Its postwar security identity is based on legalism, coalition consolidation, and deliberate restraint, but it also has industrial, scientific, and institutional capabilities that expand rapidly when political constraints change. Reliance on nuclear sharing without sovereign control, coupled with concerns about strategic abandonment and the normalization of the use of force outside legal frameworks, all undermine nuclear restraint. Any move towards Germany’s nuclear capabilities would not mean a return to militarism but a breakdown in trust in the system designed to prevent militarism. This would be particularly worrying for Germany’s neighbors.

From diffusion to entanglement: parallels to World War I

The most dangerous consequence of new proliferation is not simply the increase in the number of nuclear weapons, but the entanglement of alliances that they create. Each new nuclear state has the potential to extend the umbrella of deterrence to allies, proxies, and alliances, increasing escalation channels and delegating nuclear risks downward. The structural similarities with the pre-World War I alliance system are striking. Before 1914, dense overlapping commitments turned local crises into system-wide catastrophes, not because leaders sought war, but because treaty obligations superseded judgment. Today, nuclear entanglements recreate this dynamic under far more lethal circumstances, compressing irrevocable decisions into hours rather than weeks.

nuclear armed middle east

To see where the current incentives are going, imagine a Middle East where Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia are all nuclear-armed and facing a nuclear-armed Israel. This is not a speculative fantasy, but a direct deduction from existing abilities, declared intentions, and weakening confidence in self-control. In such an environment, deterrence no longer functions through a small number of stable rivalries, but through overlapping alliances, proxy conflicts, and credibility struggles. The crises in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, the Gulf and the Eastern Mediterranean will no longer be easily contained. Each carries the potential for nuclear escalation, leaving the region forever vulnerable to catastrophe with just one misjudgment.

conclusion

The dangers facing the international system today are not abstract. This is the foreseeable outcome of a world where we are taught that law is subservient to force and that security depends on military capability. Nuclear proliferation becomes a rational response when international law is treated as an option and military force is treated as the final arbiter of disputes. If new nuclear powers engage regional conflicts with existential stakes, the risk of escalation could become unmanageable. A just order does not create stability. It creates the conditions for regional and global nuclear disaster. The United States may sow the wind through its reckless use of military force, and the world may once again be engulfed by a nuclear storm.