The expiration of the New START Treaty on February 5th ended the last binding limits on U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces. Public debate has largely focused on fundamental questions such as whether there will be an increase in armaments, whether there will be a new arms race, and whether diplomacy can restore formal limits. But the main danger is not just the buildup of U.S. nuclear weapons. It is the emergence of a nuclear security environment that is dangerously unstable and far more difficult to control than the Cold War regime it replaced.

Strategic nuclear stability is currently being compromised by three interacting developments. First, you can quickly expand your arsenal by simply uploading warheads to existing delivery systems, rather than slowly and visibly building new delivery systems. Second, as strategic ceilings erode, competitive pressures shift toward the deployment of short-range theater nuclear weapons, reducing decision times and increasing escalation paths. Third, deterrence is moving from a bilateral to a trilateral system, with the United States, Russia, and China each having to hedge against two competitors simultaneously. These dynamics combine to create an environment in which instability propagates rapidly and unpredictably.

Uploading warheads

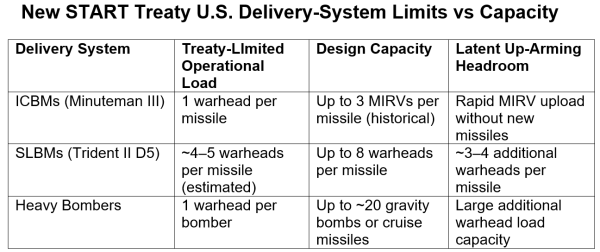

Unrestricted nuclear weapons expansion does not begin with new missiles, submarines, or bombers. That would start by putting more warheads on existing missiles and bombers. During the New START era, the United States and Russia did not dismantle the potential of their delivery systems. We just limited how much capacity is deployed and how it is counted. Therefore, warhead uploading, or placing additional warheads on existing multi-warhead missiles, remains the fastest way to increase deployed nuclear forces.

This distinction is important because uploads are relatively quick and difficult to monitor without intrusive verification. Building new submarines and missile bases takes decades and leaves an unmistakable industrial footprint. Uploads can occur during production timelines and are partially detectable only through inference and intelligence sources. As a result, the basis of the arms race shifts from surveillance to suspicion. Even if no visible accumulation occurs, you should assume that each party may be exploiting the other’s potential.

Historically, nuclear weapons were expanded not by the proliferation of warheads, but by the proliferation of launch platforms. During the 1950s and early 1960s, vast stockpiles were accumulated by fielding thousands of bombers and single-warhead missiles under pessimistic assumptions about their reliability and survivability. The escalation path today is different. Scaling is done through configuration changes that are faster, cheaper, and less observable. This makes modern military buildups, even if in absolute numbers, inherently more unstable than their Cold War predecessors.

For the United States, the most significant near-term upload potential lies in the Triad’s submarine legs. Ballistic missile submarines already carry the majority of deployed strategic warheads and are designed for flexibility in payload configuration. The United States could significantly increase the number of submarine-launched Trident ballistic missile warheads (currently 970) in a relatively short period of time. Adjustments to these missile configurations will utilize existing warheads held in reserve, rather than manufacturing new warheads. This gives unstable results. The fastest escalation paths are also the least transparent. Adversaries would have to assume that US Trident missiles can carry a full load of warheads, and would therefore seek to strengthen their nuclear forces accordingly.

Trident warheads – the more, the more deadly

Arming up also conflicts with institutional realities. The U.S. nuclear industry is already under the simultaneous strain of recapitalization and warhead life extension and replacement programs for all three pillars of the triad. Uploads increase the number of deployments without expanding the underlying industrial base, potentially masking long-term vulnerabilities with short-term numerical gains. Rhetoric about deterrence flexibility thus extends beyond an agency’s ability to sustain, monitor, and control an expanded force.

B-52 bomb bay with SRAM nuclear missiles and M-28 nuclear bombs

In addition to uploading available warheads, the United States could resume large-scale production of warheads. There is a huge cache of nuclear bomb material left over from the Cold War, including thousands of plutonium “pits” – the spherical fission cores of nuclear weapons. Over time, these materials could enable the production of thousands of new nuclear warheads.

theater nuclear deployment

As strategic restraints weaken, competitive pressures become less confined to the intercontinental system. It descends into regional and theater nuclear forces, where geography shortens timelines and political signaling becomes inseparable from escalation risk. With no binding limits on intermediate-range systems and no strategic ceiling to absorb competitive pressures, ground- and regionally-based nuclear deployments are regaining political appeal. These are cheaper, faster to deploy, and more visible to allies than strategic systems. For governments seeking reassurance and credibility of deterrence, theater systems provide effective signals of commitment, even if they result in significant instability.

Europe clearly illustrates the dangers. The continent’s dense geography and short ranges mean that intermediate-range nuclear systems operate with warning times measured in minutes rather than tens of minutes. This shortens decision-making cycles, increases the incentive to initiate a state of alert, and increases the risk that exercises and alerts are misinterpreted as preparation for an attack. During the Cold War, such deployments were restrained by the now-abandoned INF Treaty, a broad arms control framework that imposed limits and verification. Currently, the United States and Russia are actively considering deploying theater nuclear missiles.

Typhon launcher for the U.S. nuclear-capable intermediate-range cruise missile “Tomahawk”

Asia is a different but equally volatile situation. Geography favors regional strike systems, alliance structures are less formalized, and conventional and nuclear forces are more closely intertwined. As the United States adjusts its posture to assess both Russia and China, regional deployments have emerged as a way to compensate for distance and base constraints. But in Asia, the escalation ladder is less clearly delineated, and the coercion of nuclear war blurs the threshold and increases the risk of misunderstandings.

Regardless of the region, theater systems are characterized by time compression. Strategic capabilities develop over decades. Theater nuclear forces can be deployed within days. As the nuclear race becomes regionalized, the potential for misperceptions to escalate the crisis increases exponentially, even if the overall number of warheads remains relatively stable.

three-body deterrence problem

Arms control during the Cold War was based on bilateral symmetry. Because the United States and the Soviet Union were primarily dealing with one equal adversary, they were able to negotiate limits. That geometry no longer exists. Today’s strategic environment is trilateral, involving the United States, Russia, and China, each planning simultaneous conflict against the other two. In this situation, no country can match the combined arsenal of the other two countries without creating a destabilizing imbalance. Suppression for one actor creates exposure for another. Transparency that reassures one adversary can reveal vulnerabilities in another. The stabilizing logic of reciprocity collapses.

For the United States, this will create relentless upward pressure. Military forces large enough to deter Russia alone appear to be inadequate if China is included. The expansion of deterrence obligations across multiple regions further exacerbated the problem, encouraging the maintenance of margins rather than adhering to fixed caps. Russia faces a different but parallel dilemma. In a system where two other major powers possess advanced nuclear forces, maintaining strategic parity and avoiding encirclement will be paramount. Notices, opacity, and doctrinal ambiguity replace negotiated limits, further reducing predictability. China is entering the system from a small baseline, but with increasing industrial and technological capabilities. Power expansions aimed at ensuring survivability and credibility are interpreted through a worst-case lens by both other actors. Even if there is no hostility, suspicions about the Trinity arise.

The important point is that three-body instability does not require aggression. It comes from rational planning under uncertainty. Each actor tries to avoid risk. Collectively, these create excess capacity, reduced transparency, and reduced decision time. Without new arms control measures, there is little to stop this eternal arms race machine.

Growing concerns about second-tier nuclear powers

Instability at the top of the nuclear system remains unchecked. As the upper limit disappears and uncertainty increases among major powers, second-tier nuclear powers are quietly reconsidering their definition of what constitutes a “minimally adequate” deterrence force. Historically, small arsenals have been calibrated around relatively stable great power ceilings and predictable escalation ladders. That frame of reference is dissolving. Increased power potential, theater deployment, and trilateral competition reduce confidence that small forces can maintain deterrence in a crisis. The response is likely not to be a sudden epidemic of breakouts, but rather gradual buffering: modest increases in numbers, diversification of delivery systems, and a greater emphasis on survivability. Although these adjustments are reasonable responses to uncertainty, they expand the distribution of nuclear capabilities and increase the number of actors operating under compressed schedules.

conclusion

Taken together, these dynamics represent an evolution of the nuclear order, not a return to Cold War competition, but one that is more complex, more dangerous, and more ungovernable. Arm up to increase opacity. Theater reduces decision time. Tripartite deterrence undermines bilateral balance. The second stage of realignment spreads the risk externally. None of this requires malicious intent. Each development logically results from the erosion of formal restrictions and coercive mechanisms. As more actors wield greater weapons under shorter decision-making horizons and without constraining frameworks, the risk of catastrophic regional or global nuclear war increases correspondingly. The United States bears central responsibility for this outcome, not through any single decision, but through its systematic abandonment of institutional structures designed to limit nuclear competition and reduce the risk of catastrophic war.