Rare earth elements (REEs) are at the core of modern military power. These materials are incorporated into jet engines, precision-guided weapons, radar systems, and advanced communications, enabling capabilities that give the U.S. military a technological edge. In a sustained crisis or great power conflict, disruptions to the REE supply chain could spill over into U.S. defense production, delaying or halting critical programs. Ensuring access to these materials is therefore not just a matter of industrial policy, but also a matter of national security.

Rare earths are a small group of metals with extraordinary magnetic, thermal, and electronic properties that are essential to modern military technology. The global supply chain for these materials is highly concentrated, with the People’s Republic of China dominating mining, processing, and magnet production. Recently, China retaliated against US import tariffs that restricted REE exports. This article discusses the role of REEs in weapons production and the foreign policy implications of controlling their supply.

Rare Earth Elements: Why the Military Needs Them

There are 17 types of rare earth elements. Their unique combination of magnetic strength, heat resistance, and optical properties make them essential to modern weapons systems. REEs power many of the most sophisticated defense systems, from jet engines to precision-guided weapons. Many are abundant but difficult to extract and process. Few countries have invested in the costly and environmentally demanding refining processes required for large-scale use.

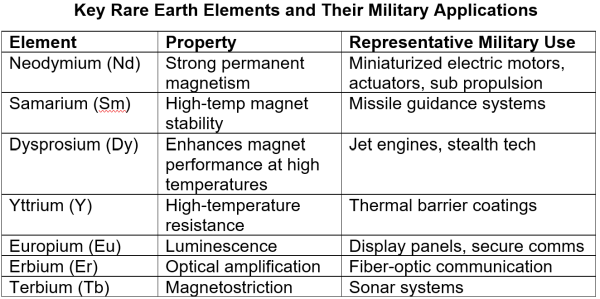

Rare earth elements pervade all areas of modern warfare. These are essential to the performance, efficiency, and stealth of advanced systems. Its strategic value lies not only in its technical properties, but also in its non-substitutability in important applications. The table below correlates the major REE materials and their military applications.

Strategic competition and national security implications

Rare earth elements have become geopolitical tools. Against the backdrop of intensifying US-China competition, control over processing and magnet production has become a critical vulnerability for the Western defense industry. Managing REE supplies has become an integral part of national security strategies.

Supply chain vulnerabilities and strategic risks

Although rare earth elements are mined in multiple countries, China accounts for the majority of the world’s refining capacity and magnet production. This concentration creates a single vulnerability for industrial defense bases around the world. China’s recent REE export restrictions demonstrate the strategic impact this can have.

Rare earth mining – it’s a big job

Rare earths in the China/US trade war

When the Trump administration raised tariffs on Chinese imports this year, China retaliated by restricting REE exports. The following table describes the evolution of this trade dispute.

This timeline shows how traditional trade disputes quickly gain strategic importance. In response to the U.S. tariff hike in early April, China urged targeted responses in the form of export restrictions on rare earths, an area in which the Chinese government has significant influence. A series of mutually beneficial moves followed, extending the dispute from tariffs to critical materials and industrial capacity.

By October, China had expanded its regulations beyond raw materials to include processing technology, signaling its intention to use its supply chain advantages as a strategic tool. The United States framed the issue as a national security issue and responded with the threat of tariffs. This sequence highlights how critical mineral supply chains function as instruments of geopolitical influence, turning what appears to be economic disagreements into contests for technological and strategic advantage.

Policy response and supply chain diversification

The United States and its allies are beginning to address REE vulnerabilities through a combination of domestic production, sourcing from allies, recycling, research into alternatives, and strategic stockpiles. These efforts are long-term efforts, but essential to maintaining our technological edge.

Achieving complete self-sufficiency in rare earth elements in the United States would require an estimated $22 to $40 billion in capital investment over approximately 7 to 12 years, covering both light and heavy elements and specialty applications. This includes building sufficient mining and separation capacity to meet domestic demand for light rare earth elements such as neodymium, praseodymium, cerium and lanthanum, as well as adding targeted capacity for heavy specialty rare earth elements such as dysprosium, terbium, yttrium and europium, which are essential for defense, aerospace and advanced optics. Additional investments will fund NdFeB magnet production, metal and alloy plants, stockpiling and recycling infrastructure to cushion supply shocks.

Defense materials autarchy?

The cost of establishing self-sufficiency in rare earth elements in the United States is significant, in the tens of billions of dollars over 10 years, but rare earths are just one critical input among the many needed to sustain a modern defense industrial base. Achieving true defense materials autarky will require massive investments across many other fundamental areas, including semiconductors, energy, specialty metals, shipbuilding, advanced composites, precision manufacturing, and power technology.

The U.S. defense industry relies on an estimated $125 billion to $210 billion annually in foreign-sourced materials, components, and systems concentrated in several strategically important categories, including semiconductors, advanced electronics, rare earths, energy, specialty metals, high-end machine tools, and shipbuilding materials. These imports are often small in volume but have significant supply chain influence, so disruptions can have a disproportionate operational impact.

Replacing these imports with fully domestic production will require building the entire upstream and midstream supply chain. On a national scale, this means trillions of dollars in low- to mid-term capital investment over 10 to 20 years, as well as massive workforce expansion and long-term industrial adjustment. In short, although US defense import dependence is relatively modest in dollar terms, it is strategically concentrated and costly to eliminate, making autarky a long-term, resource-intensive undertaking rather than a rapid replacement.

Achieving defense material autarky in the United States would require a level of central economic planning and coordination that is fundamentally at odds with the structure of the American political economy. The scale of investment, sequencing, and labor mobilization involved cannot be achieved through market forces alone. It requires a long-term commitment, prioritized capital allocation, synchronized infrastructure construction, and central control of critical supply chains. But the U.S. system is built around fragmented private investment, fragmented regulators, and short political time horizons, making sustained strategic coordination difficult.

conclusion

Rare earth elements are an industrial imperative for modern military forces. These enable system performance and reliability that define strategic advantage. Because REE production is concentrated in the hands of a few foreign producers, they are also a source of vulnerability. Managing this risk requires deliberate investment, coordination, and innovation. The Trump administration’s unstable and erratic international economic policies are inconsistent with the coherent strategic planning needed to build a stable defense infrastructure. Facts are stubborn things, and the economic facts about securing REEs and other strategic supplies will ultimately determine the direction of U.S. trade policy.