Armed conflicts across Africa are commonly described as the aftermath of colonialism, the interference of outside forces, the spread of jihadism across borders, or, at the crudest level, the outbreak of tribal conflict. Each of these stories captures something valid. None of them, by themselves, come close to explaining the patterns, persistence, and fluctuations of armed conflict across the continent. The result is a simplistic discourse that is morally satisfying, politically expedient, and strategically useful.

What is surprising about African wars is not just their frequency, but their variety. Even though conflicts in the Sahel, Sudan, eastern Congo, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Nigeria share superficial characteristics such as weak states, porous borders, and external intervention, they differ markedly in structure, actors, and trajectories. Treating these wars as examples of a single underlying pathology, such as colonial legacies, ethnic hostilities, terrorism, or climate stress, obscures more than it reveals.

A more accurate explanation begins with an outdated premise. Conflicts in Africa are the product of multiple interacting causes that develop simultaneously and at different rates. Colonial inheritance is important, but it does not operate in isolation. Postcolonial governance, political economy, demographic pressures, security sector dynamics, resource rents, and external shocks all interact to produce distinct conflict patterns. Wars continue not because Africa is stuck in an endless past, but because its fragile political systems are under stress from multiple directions simultaneously.

Typology of modern African conflicts

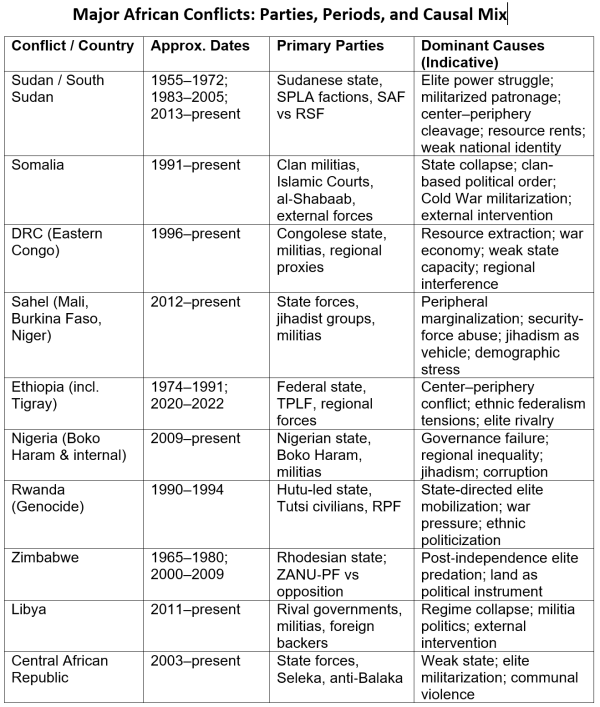

A serious analysis must begin with an explanation. What follows is not an exhaustive catalogue, but rather a general listing of the dominant conflict regimes currently shaping the continent.

State fragmentation and elite power struggles characterize conflicts such as Sudan, South Sudan, Libya, and the Central African Republic. In such cases, the central problem is not social collapse but competition among armed elites for control of state resources. Violence functions as a means of negotiation within divided sovereignty.

Much of the Sahel region and northern Mozambique is defined by insurgency in weaker surrounding countries. Here, jihadist movements are best understood not as the main cause, but as a means of exploiting marginalization, predatory security forces, and a lack of reliable governance in the local periphery.

A protracted war economy prevails in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where violence persists not because victory is impossible, but because the conflict itself is a form of political and economic organization. Armed groups function as exploiters embedded in local and global markets.

Center-periphery and identity-based state crises are seen in Ethiopia and Nigeria, where the state remains intact but its legitimacy is contested by ethnic, regional, or religious blocs. These conflicts are political struggles over inclusivity and power distribution, not failures of state survival.

Almost complete state replacement, as exemplified by Somalia, represents a completely different category. that is, the collapse of central authority and the subsequent emergence of alternative governance structures rooted in clans, commerce, and coercion.

This diversity alone should dispel the idea that African wars share a single cause. it’s not. They share overlapping pressure and are combined in different proportions. The causes of conflict listed in the table below do not definitively describe a single case, but indicate multiple interacting pressures that shape conflict.

The human cost of these wars is devastating. In most cases, the majority of deaths are not from the fighting itself, but from displacement, starvation, and the breakdown of basic governance, and the costs continue to mount long after the headlines have faded.

Somalia refugee camp

Proportional causation and the limits of colonial explanations

There is no doubt that colonialism shaped Africa’s political geography, institutional succession, and patterns of exploitation. But it did not uniformly determine the outcome, nor does it explain why colonized societies diverged so sharply after independence.

Zimbabwe exemplifies this point. Although Rhodesia’s rule was brutal and exclusive, it did not leave a structurally ungovernable state in 1980. Zimbabwe inherited functioning institutions, productive agriculture, and an educated elite. The ensuing collapse was primarily caused by post-independence political choices: elite dispossession, violent land grabs as a means of regime survival, and the deliberate destruction of institutional capacity. Colonialism created constraints. It didn’t affect the outcome.

The Hutu-Tutsi genocide in Rwanda makes the same point in a more tragic way. Colonial rule reinforced ethnic categories and embedded grievances, but genocide was not an automatic product of decolonization. It was a deliberate, state-driven political project carried out in a context of war, regime instability, and international abandonment. Colonialism formed the raw material of identity. Postcolonial elites weaponized it.

Somalia is at the opposite end of the spectrum. The colonial legacy explains little about its trajectory after 1991. The country’s disintegration and restructuring were caused by clan structures, Cold War militarization, and the lack of a shared national political solution. Treating Somalia as a colonial failure misses the reality that a non-state order is emerging, one that external actors have repeatedly destroyed.

The lesson is not that colonialism was irrelevant, but that the causes operate in different proportions. Treating one factor as universally determinative guarantees analytical fallacy.

Why my diagnosis persists

If Africa’s wars are so diverse, why are they so often misread? Part of the answer lies in the institutional limitations of U.S. foreign policy. The American diplomatic apparatus was built to manage relations between bureaucratized states, not a layered political system in which power operates through informal networks, armed groups, and negotiated legitimacy. Elections, constitutions, and formal ministries are routinely mistaken for seats of power.

There have always been individual diplomats and analysts who understand these dynamics. What the United States has not developed so far is the sustained institutional capacity to translate that understanding into policy. Knowledge was personal and perishable, while decision-making gravitated toward ideological templates such as Cold War anti-communism, post-Cold War democratization, and post-9/11 counterterrorism. Each framework flattened reality in different ways. They all prioritized action over understanding.

Somalia as a textbook failure

Somalia is the clearest example of why monocausal narratives fail. For more than three decades, outside actors have treated the country as a humanitarian emergency, a failed state, a hotbed of terrorism, and a laboratory for nation-building, often simultaneously. Each framing justified intervention. No one engaged with the political reality that emerged after the collapse of central authority: a fragmented but functional order rooted in local governance, commerce, and coercion.

Yes, colonial partition and border demarcation were important, but they did not mechanically cause state collapse. Somalia’s post-independence trajectory was shaped by interacting forces, including Cold War militarization, authoritarian rule and patronage, the politicization of clan networks, repeated droughts and price shocks, and the sudden withdrawal of external support that had supported coercion. Even if the center is broken, it doesn’t just “disappear.” Authority was fragmented into competing forms of governance, including local governments, corporate-backed security arrangements, clan-based conflict systems, and later Islamic courts, each offering partial orders in exchange for loyalty, taxation, or protection.

The collapse of the early 1990s illustrates the political economy of humanitarian catastrophe. Hunger was not just a weather phenomenon. It was a market and security event. Armed groups controlled roads, ports, and relief corridors, turning food into revenue and leverage. This reality made external intervention inherently political. Providing aid meant choosing who benefited from survival logistics. Outside actors often treated Somalia as a morality play (a rescue mission or a cautionary tale), when in reality it was a very material struggle over rent, displacement, and forced entry.

Somalia also exposes the United States’ repeated mistake of treating counterterrorism as a strategy rather than an aid tool. That is, disrupting networks while leaving behind the locally negotiated, incentive-based foundations of legitimacy that determine whether authority is consolidated or fragmented.

What should U.S. policy be?

A better U.S. approach to Somalia would have required reframing the problem along three intertwined dimensions, rather than oscillating between humanitarian intervention and counterterrorism.

Treat Somalia as a political economy, not a rescue mission.

The central challenge was not to restore a theoretically unified state or to carry out ad hoc relief operations, but to rebuild incentives within a conflict economy, supporting authority where security, conflict resolution, and commerce were aligned, and undermining authority where tolling and rent collection predominated.

Power that is subordinate to legitimacy rather than replacing it.

Military force can disrupt perpetrators of violence, but it cannot create lasting authority. The enduring mistake was to treat counterterrorism as a strategy rather than a support tool. Recognizing that legitimacy in Somalia is negotiated, progressive and locally based, security assistance should have been explicitly conditioned on civilian protection and institutional performance. When power becomes the organizing principle, governance becomes incidental and instability is perpetuated.

Anchoring interventions in local and material realities.

Instability in Somalia is by no means purely domestic. External patterns, neighborhood conflicts, and cross-border economic flows continually shape outcomes on the ground. A serious policy would have treated regional diplomacy, aid logistics, and market functions as core stabilization tools rather than secondary concerns. In particular, humanitarian aid needed to be designed to minimize capture and war wages, recognizing that “neutral aid” in a fragmented security environment was often an illusion.

The missteps in U.S. policy in Somalia are thus indicative of a broader pattern. This means a continued failure to engage with complex political economy as it stands, replacing temporary humanitarianism and a narrow security perspective with a sustained, incentive-driven national strategy.

US airstrikes in Somalia in 2025 — continuing a decades-long pattern of ineffective military interventions

Cost of simple diagnosis

The greatest danger of monocausal thinking is not analytical error but political stupidity. Simplistic explanations create the illusion that complex conflicts can be easily resolved. These invite great powers to intervene with tools designed for problems that do not exist in the way they were imagined.

When African wars are reduced to terrorism issues, tribal pathologies, or proxy conflicts, crude interventions follow in response, arming loyalists, propping up weak regimes, and freezing conflicts into permanent stalemates. And African societies bear the human costs of death, destruction, and displacement. External forces accumulate sunk costs, strategic distractions, and institutional corruption. Although these failures are not unique to the United States, American policy is distinctive in the scale of its failed interventions and its confidence in applying ill-fitting templates.

This intellectual flaw was evident in the Trump administration’s public and false identification of South Africa as the site of racial genocide. This was not just a factual error. It was the culmination of decades of analytical decline in which complex political institutions were reduced to stories of slogans and grievances.

South Africa’s problems are real and serious. They are not genocidal. That such a misreading could be expressed at the highest levels of the U.S. government is indicative of a deeper failure that this article traces: a sustained inability to understand Africa’s political reality from its own perspective. The intellectual posture of US foreign policy toward Africa has become the cognitive equivalent of TL;DR: a refusal to engage with complexities that ensure misunderstanding.