Eve, here. Although depressing, climate engineering, also known as geoengineering, is inevitable. Not only are our putative improvers not doing remotely enough to slow the pace of global warming, they are flat-footed to make things even worse with their AI-crazed dreams and associated construction of energy-wasting data centers. Even with electricity, the demand is so high that it seems heroic and optimistic to assume that everything can or will be powered by solar or nuclear power.

Written by Kelsey Roberts, Postdoctoral Fellow in Marine Ecology, Cornell University. Dartmouth, Massachusetts; Daniele Visioni, assistant professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University; Morgan Raven, Associate Professor of Marine Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Tyler Rohr, IMAS ARC DECRA Fellow/Senior Lecturer, University of Tasmania. Originally published on The Conversation

Climate change is already causing dangerous heat waves, rising sea levels and changing the oceans. Even if countries fulfill their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, global warming will exceed the limits that many ecosystems can safely handle.

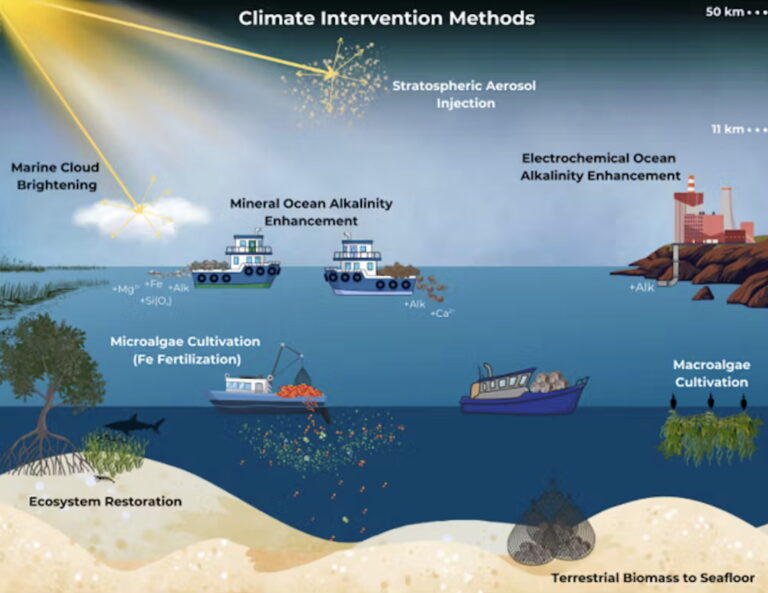

This reality is motivating scientists, governments, and a growing number of startups to look for ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or at least temporarily halt its effects.

But these climate interventions come with risks. There are particular risks to the ocean, which is the world’s largest carbon sink and the basis of global food security.

Our team of researchers has spent decades studying the ocean and climate. A new study analyzed how different types of climate interventions can affect marine ecosystems, for better or worse, and where more research is needed to understand the risks before anyone tries them on a large scale. We have found that some strategies are less risky than others, but no strategy is completely free of results.

What does climate change intervention look like?

Climate change interventions fall into two broad categories, each with very different functions.

One is carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Tackling the root causes of climate change by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The ocean already absorbs nearly a third of anthropogenic carbon emissions annually and has enormous capacity to hold even more carbon. Marine carbon dioxide removal technologies aim to increase natural carbon uptake by changing the biology and chemistry of the ocean.

Some of the methods of climate intervention that affect the ocean, such as iron (Fe) fertilization. Vanessa Van Helden/Louisiana Sea Grant

Biological carbon removal methods capture carbon through photosynthesis in plants or algae. Some methods, such as iron fertilization and seaweed farming, promote the growth of marine algae by providing them with more nutrients. Some of the carbon captured during growth can be stored in the ocean for hundreds of years, but much of it escapes into the atmosphere as the biomass decomposes.

Other methods involve growing plants on land and submerging them in deep, low-oxygen water that decomposes slowly and slows the release of the carbon they contain. This is known as anaerobic storage of terrestrial biomass.

Another type of carbon dioxide removal does not require biology to capture carbon. Enhanced ocean alkalinity chemically converts carbon dioxide in seawater into other forms of carbon, allowing the ocean to absorb more from the atmosphere. It works by adding large amounts of alkaline substances such as crushed carbonate or silicate rocks such as limestone or basalt, or electrochemically produced compounds such as sodium hydroxide.

How it works to increase ocean alkalinity. Shiro.

Adjusting solar radiation is a completely different category. This acts like a sunshade. Although it doesn’t remove carbon dioxide, it can inject small particles into the atmosphere to brighten clouds or reflect sunlight directly into space, replicating the cooling seen after large volcanic eruptions, reducing dangerous effects such as heat waves and coral bleaching. The appeal of solar radiation adjustment is its speed. It could cool the planet within a few years, but it would only temporarily mask the effects of still rising carbon dioxide levels.

These methods can also affect marine life

We considered eight intervention types and assessed how each would impact marine ecosystems. It turns out that all of this has clear potential benefits and risks.

One of the risks of drawing more carbon dioxide into the ocean is ocean acidification. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms an acid. This process is already weakening oyster shells and damaging corals and plankton, which are essential to the ocean’s food chain.

Adding alkaline substances, such as ground carbonates or silicate rocks, can reduce its acidity by converting additional carbon dioxide into less harmful forms of carbon.

In contrast, biological methods capture carbon in living biomass, such as plants or algae, but release it back as carbon dioxide when the biomass decomposes. In other words, the effect on acidification depends on where the biomass grows and where it subsequently decomposes.

Another concern with biological methods concerns nutrients. All plants and algae require nutrients to grow, but the ocean is highly interconnected. Fertilizing the surface of an area can make plants and algae more productive, but it can also suffocate the ocean below and disrupt fisheries thousands of miles away by depleting nutrients that would otherwise be transported by ocean currents to productive fishing grounds.

Enhancement of ocean alkalinity does not require the addition of nutrients, but some mineral forms that are alkaline, such as basalt, introduce nutrients that can affect growth, such as iron and silicates.

Altering solar radiation does not add nutrients, but it can change the circulation patterns that move nutrients.

Acidification and nutrient changes benefit some phytoplankton and disadvantage others. As a result, changes occur in the phytoplankton mixture. If different predators prefer different phytoplankton, the subsequent effects can travel all the way up the food chain and ultimately impact the fisheries that millions of people depend on.

The least risky option for the ocean

Of all the methods we considered, we found that electrochemical ocean alkalinity enhancement poses the least direct risk to the ocean, but it is not without risk. Electrochemical methods use electrical current to separate brine into alkaline and acidic streams. This produces a chemically simple alkalinity with limited biological impact, but the acid also needs to be neutralized or safely disposed of.

Other lower-risk options include adding carbonate minerals to seawater that increase alkalinity with relatively few pollutants, or submerging land plants in deep, low-oxygen environments to store carbon long-term.

Still, there are uncertainties with these approaches and further research is needed.

Scientists typically use computer models to investigate such methods before testing them on a large scale in the ocean, but models are only as reliable as the data on which they are based. And many biological processes are still poorly understood and cannot be included in models.

For example, the model does not capture the effects of trace metal contaminants in certain alkaline materials or how ecosystems reorganize around new seaweed farms. To accurately include such effects in models, scientists must first study them in the laboratory and sometimes in small-scale field experiments.

Scientists are investigating how phytoplankton take up iron as they grow off Heard Island in the Southern Ocean. The region is normally low in iron, but volcanic eruptions may provide a source of iron. Shiro.

A cautious and evidence-based move forward

Some scientists argue that the risks of climate intervention are too great to even consider and that all related research should be halted, as it is a dangerous distraction from the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

we disagree.

Commercialization is already underway. Investor-backed ocean carbon removal startups are already selling carbon credits to companies such as Stripe and British Airways. Meanwhile, global emissions continue to rise, and many countries, including the United States, are backing away from their emissions reduction commitments.

As the damage from climate change worsens, pressure may increase for governments to rapidly deploy climate change interventions without a clear understanding of the risks. Scientists now have an opportunity to carefully study these ideas before the Earth descends into climate instability and society is forced to accept untested interventions. That window won’t stay open forever.

Given these risks, we believe the world needs transparent research that eliminates harmful options, tests promising options, and halts them if impacts are found to be unacceptable. No climate change intervention may be safe enough to implement at scale. However, we believe that decisions should be made based on evidence, not market pressure, fear or ideology.