Eve here. This is a case study, but while Cape Town drugs were at risk for drying local government tap water, it shows that SEM occurs when climate stress becomes acute. The short version means that Rich has taken steps that he helped himself but not others, and he is taking action, making it impossible for the community to be dealt with in a critical way.

Alexander Abazian, Cassandra Cole, Kelsey Jack, Kyle Meng, and Martin Bisters were originally published in Vokseu

The growth in urban areas around the world is facing water shortages. Focusing on the long droughts Cape Town experienced between 2015 and 2018, this column examines how adaptation has shaped the outcomes for city residents and their local water operators. Policy measures, including high prices and usage restrictions, have avoided city exhausting water, but have reduced demand among wealthy households to exchange away from local government water, and undermined the useful ability to cross-subsubsize consumption of low-income households. Mandatory tariff reforms have led to more efficient pricing schemes that maintain support for low-income households.

Climate change is no longer a distant threat — it is shaping the economy around the world. As a result, responses to climate change are increasingly changing towards adaptive measures to attenuate the impact of ismedie (Kala etal. 2023). An improved focus on adaptation poses two challenges for polymakers (Carleton et al. 2025). First, how and how can public adaptation policies be designed to explain their impact on private actors’ own adaptation decisions? Second, given the inosai flames in access to adaptation across people and communities, what does the climate-driven shock mean to inequality? And how are they shaped by both existing and new politics?

The long-term water crisis in Cape Town, South Africa provides a prominent example of the Bost of these challenges. From 2015 to 2018, the city experienced a long-term medication that cities were confused by “day zero.” A recent paper (Abajian etal. 2025) examines how adaptation of the shape outcomes of Cape Town residents and their local water operators (both before and after Droo) has been adapted. The policy was successful with redundancy and zero days was avoided, but this policy’s response to DROOUGH shows that it induced dramatic adaptation of wealthy households, such as groundwater well drilling and practical use from urban water. In addition to destabilizing the financial viability of utility projects, the reduction in demand from better households undermined the useful ability to cross-subscisse the consumption of households in low-being. Local governments ultimately responded by reforming tariffs after drug Trow to a more efficient pricing scheme that maintains support for low-Inkord households.

Day Zero Experience is an optimistic story about efficient adaptation and autory about private responses to climate change and public regulations for climate-sensitive products and services. Similar to public road, school or electricity regulations, the availability of private alternatives can have a significant impact on the financial and cost distribution of all users. More and more urban areas, such as Mexico City and Beijing, are facing water shortages (Werner et al. 2013), and these issues become the forefront and centre of climate adaptation policy.

Day Zero: Cape Town Drawf

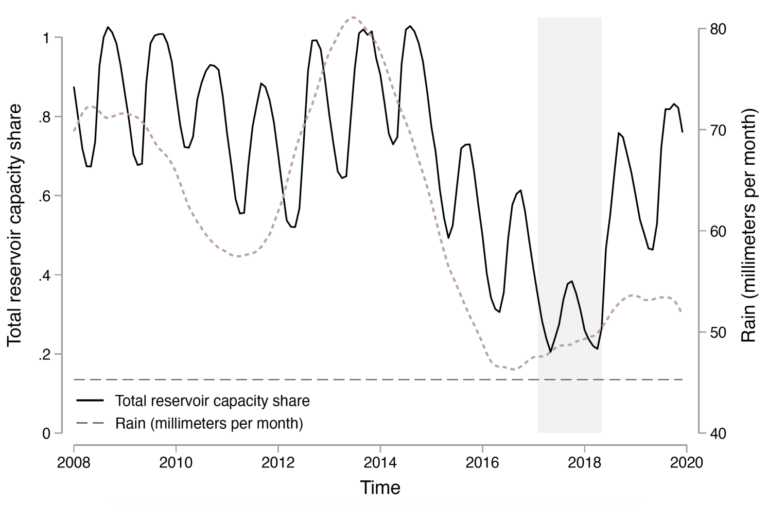

Cape Town is South Africa’s second Largansto city, and is heavily dependent on natural rainfall as a source of water supply for municipalities (Cape Town 2020). The city is cross-subsissizable consumption among low-income households using a municipal water-increasing block tariff (IBT) pricing model. The IBT charges marginal costs to high consumers to cover the subsidies, while allowing these consumers to pay the subsidies interest rate. However, as shown in Figure 1, multi-andal drug drugs beginning around 2015 have begun to make existing consumption patterns unbearable. During DROOUGH (shady area in Figure 1), city reservoirs were depleted to near critical levels associated with day zero (13.5% horizontal dashed line). Starting in 2017, local governments began taking UN prince measures to reduce consumption, including sudden price increases, usage restrictions and public information campaigns.

Figure 1 Reservoir levels fell sharply during DROOUGH, leading cities to emergency response

No evacuation dates

Policy measurements – conservation campaigns, higher prices, and usage restrictions – ultimately saved the city from scratch. Total housing usage has decreased by about 50% from pre-crisis levels (Booysen etal. 2019, Brühland Visser 2021). However, these reductions were very uneven throughout the household wealth distribution. Wealthy households consumed one-fold lower water before the crisis (Cook etal. 2021), and saw the sharpest decline (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average local government water use by household income before, during and after the crisis (in favor by housing value)

This was part of the behavioral changes that resulted from conservation campaigns, public pressure, and sensitivity to price of demand (Booysen et al. 2018, Bruhl et al. 2020, Brick et al. 2023). Many wealthy households replaced them with private groundwater by drilling wells and boreholes. Figure 3 shows the number of drilling licenses over time. Underreporting means that the current number is likely to be much larger. The ability of wealthy households to stay away from public water contributed to a sharp decline in consumption shown in Figure 2, leading to practical consumption of providing water more publicly than poor households at the peak of the crisis. Personal adaptation had a wide range of implications. It erodes the revenue base of local government utilities and changes the supply costs that Ontos could not afford personal alternatives. The cost shift caused by private adaptation means that the overall share of water costs supported by the lowest domestic households was news of the wealthiest households at the peak of today’s crisis.

Figure 3 Groundwater drilling applications emerged among wealthy households during the crisis

Note: This diagram shows the cumulative counts of groundwater projects registered with municipalities and likely to be 10 times the current number.

At the same time, the city’s water tariff structure has previously become unsustainable due to cross-subcidence of low ingredients, relying on large numbers of users. On the lack of income from substitution to groundwater in wealthy households, the utility will introduce a fixed charging component in the water tariff. After the addition of fixed charges, total (bush fixed and volumetric capacity) charges increased by about 4% at mandatory level, triggered by DROOUGH. Fixed fees also covered connection sizes intended to replace the power of attorney for wealth. This offset the sub-in-Velvecost shift caused by substitution for groundwater in wealthy households. To further address distribution concerns, low-income households also declared a monthly free free water allocation. Without these poll changes, the distribution of costs would have been very appealing after the obligation.

The shock-induced changes in PIOLY have moved municipalities to a more efficient pricing regime, but changes in overall wealth dexal consumption patterns continued until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (when analysis is over). It is likely that wealthy households who invested in groundwater wells continued to rely on them, keeping demand for urban water lower than before the crisis. This highlights important issues in climate adaptation. Without carefully designed politics, private adaptation could exacerbate inequality and have lasting effects leading to the financial viability of essential public services.

Utility policy facing climate change

Our study shows that some features of the Cape Town experience may help guide utility policies in other climate-sensitive environments. First, the demonstrated crisis is the volume pricing model vulnerability to lower demand (Borenstein 2022), which becomes nude as rarity increases. In Cape Town, this was addressed by the introduction of fixed fees into the tariff structure. While this is a sign of the discovery of the possibility that the crisis could induce policy innovation (van der Straten and van der ploeg 2024), not all policy liability provides information the same information as Cape Town’s responsibility. Second, Cape Town’s experience highlights the effectiveness of targeted subsidies for vulnerable populations. During and after the crisis, Cape Town was blessed with free allocations that coordinated water subsidies for low-inchrome households and required free allocations as stipulated under existing laws (Muller, 2008). Households face standard price schedules at consumption levels above the amount due to basic needs, encouraging conservation while lending capital.

Finally, by studying both DROOUGH and pole responses to policy-responsible households, an analysis of Cape Town’s experience highlights the interaction between public and private adaptation. The increase relying on private groundwater extraction is at groundwater levels that cause dramatic dramatic drama in wealthy neighbours, thus raising broader concerns about the long-term sustainability of private use here (Figure 4). At the same time, bringing public water demands impact utility revenues and create financial externalities across users. Similar patterns have been developed, for example, in response to rising electricity prices and reliability of organized grids, such as the adoption of private rooftop solar (Brehm et al., 2025). Future climate adaptation policies need to predict action responses. It may also vary between income groups.

Figure 4 Groundwater levels drop during Drouckt near the wealthy Cape Town district, but not in other neighborhoods