The recent removal of Nicolas Maduro from the Venezuelan presidency is a dramatic development after more than two decades of socialist experiment under Hugo Chávez and Maduro, marked by expropriation, macroeconomic mismanagement, and political repression.

Although there is much uncertainty about Venezuela’s economic and political future, economics may provide some guidance and warning. One such lesson concerns the dangerous temptation to base economic recovery solely on the oil sector. Venezuela’s future will largely depend on the quality of its future institutions and policy choices.

In present-day Venezuela, the judiciary, electoral authorities, prosecutors, and police have lost their independence. Restoring personal and political rights through institutional reform that allows Venezuelans to once again hold political leaders and government officials accountable must be a top priority.

Second, private property rights and free enterprise must be restored to unleash the creative potential of the Venezuelan people.

Finally, leaders should look to the design of foreign exchange policy and the management of oil rents, both of which are essential to avoid a new cycle of dependence, rent-seeking, and stagnation.

A political transition that includes meaningful electoral reform and credible guarantees of fair competition is likely to be accompanied by a gradual normalization of relations with the United States. Such normalization could partially lift sanctions and allow new participation of private oil companies, especially foreign oil companies, in Venezuela’s energy sector. Given the country’s vast proven reserves and aging but recoverable infrastructure, even modest institutional improvements could lead to significant increases in oil production and export revenues. These revenues would provide a rare opportunity to stabilize the country’s finances, begin repaying defaulted external debt, and restore Venezuela’s confidence in international capital markets.

But this opportunity comes with well-known dangers. The most important of these is the risk of Dutch disease. In other words, resource booms tend to raise the real exchange rate, weaken non-resource trading sectors, and fixate economic structures without diversification. Venezuela’s historical experience provides ample warning. During previous oil booms, exchange rate appreciation and fiscal waste decimated agriculture and manufacturing, increased import dependence, and strengthened the political power of rent-seeking coalitions. A serious reconstruction strategy must therefore treat exchange rate policy not as a technical afterthought, but as a central pillar of economic reform.

To avoid Dutch disease, as I have argued elsewhere, we need to resist sustained local currency appreciation, even in the face of rising export earnings. An arbitrary appreciation of the currency would make non-oil exports uncompetitive and hinder the revival of a sector vital to long-term growth and employment. This does not necessarily mean a return to strict exchange controls (the disastrous consequences in Venezuela are well documented), but suggests the need for carefully designed institutions. Curtailing foreign currency inflows, accumulating foreign assets, and institutional mechanisms that prevent oil revenues from being overspent domestically will all play a role in maintaining a competitive real exchange rate.

Closely related to the successful design of foreign exchange policy is the issue of oil rents. A central political and economic challenge for post-socialist Venezuela will be to prevent these rents from being captured by entrenched public and private interests. Without reliable constraints, oil revenues tend to foster corruption, clientelism, and fiscal irresponsibility, undermining both democracy and economic freedom. The creation of a dedicated ‘sink fund’ is therefore worth serious consideration. Unlike traditional sovereign wealth funds, which aim to maximize profits and smooth consumption, the sink fund will be tasked with a limited and transparent mandate to systematically repay Venezuela’s external debt over a foreseeable period of time.

Pumping a significant portion of oil revenues into such a fund would have several benefits. First, it would reduce immediate domestic spending pressures, thereby supporting exchange rate stability and mitigating Dutch disease. Second, it would help rebuild Venezuela’s reputation as a responsible borrower, lower future borrowing costs and expand access to international finance. Third, keeping oil rents outside the discretionary control of everyday politics would limit opportunities for rent-seeking and demonstrate a credible commitment to fiscal discipline.

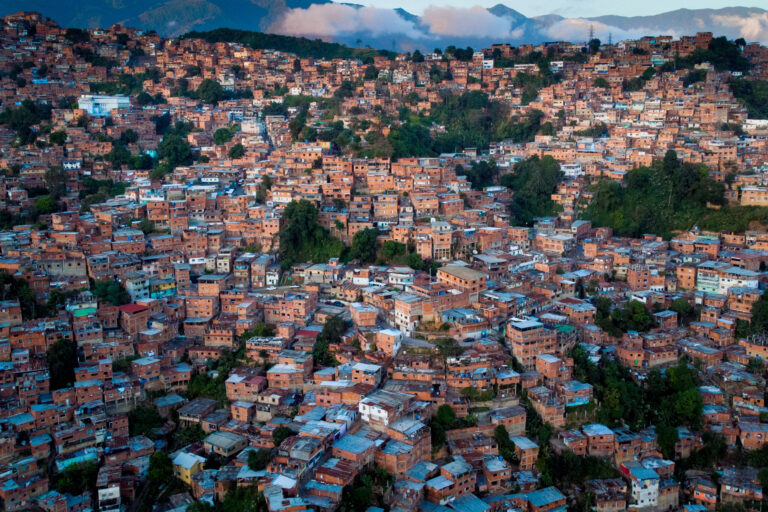

Over time, restoring basic protections for private property and free enterprise will help restore economic activity outside the oil sector. Venezuela once had a relatively diversified economy by regional standards, with significant capacity in agriculture, manufacturing, services, and human capital-intensive industries. Although much of this capacity has been destroyed or relegated to the informal sector, it has not completely disappeared. The Venezuelan diaspora, now numbering in the millions, represents a particularly important source of skills, entrepreneurial experience and international connections. If institutional reforms are credible and sustainable, many expatriates may choose to return home or invest from abroad, accelerating rebuilding and diversification.

Perhaps allowing the private sector to make profit and generate income could deflect the political demands of poor citizens for public transfers. Unless it is understood and implemented, rent-seeking will become irresistible and oil rents will once again be dissipated and political representatives will become corrupt as government revenues diverge from the broader welfare of the Venezuelan people and its economy.

In this broader context, exchange rate policy and oil rent management should be understood as enabling conditions for deeper transformation. The goal is not simply macroeconomic stabilization, but the restructuring of a society in which economic opportunity is separated from political privilege. By avoiding currency overvaluation, protecting oil revenues from plunder, and prioritizing debt service over short-term consumption, a post-Maduro Venezuela could lay the foundations for sustainable growth and true reintegration into the global economy.

None of this is easy. Success depends as much on luck as on politics as on technical design. However, if the assumptions of political normalization, institutional reform, and the resumption of oil production hold, careful management of exchange rates and rents could ensure that Venezuela once again encounters abundant resources, rather than missing out on another chance, as a source of recovery.

Leonidas Zelmanowitz is a senior fellow at the Liberty Foundation and an adjunct instructor at Hillsdale College.