Eve, here. I run this article as a conversation facilitator and critical thinking exercise. I must confess that I am not a fan of the Rousseauian romanticization of pre-modern living conditions. Until recently, Hobbes was right when he described human life as “disgusting, brutish, and short.” The sad fact is that increasing living standards requires the accumulation of surplus. This requires some formalization of how this surplus is held and used. The result is something like a state.

I don’t mean to be harsh, but the underlying logic seems like a Manichean fallacy. The evolution of civilization has produced what appear to be bad outcomes, especially from a fairness perspective, so the opposite would be better. In my opinion, history is path dependent. There were many other possible outcomes.

Although Neuberger has his own concerns, the general tenor of his thinking is consistent with what G. Elliott Morris describes as America’s new floating voters: anti-establishment voters. From new post:

In 2016 and 2024, Donald Trump won over so-called “anti-establishment” voters, including many with progressive beliefs. So say political scientists Christopher Williams and Leon Coccaya in a new paper comparing the role of anti-establishment ideology and political preferences in explaining Trump’s two victories and his 2020 loss. Williams and Kokaya used survey data to identify key groups of floating voters who distrust both parties, believe the elites are corrupt, and believe the political system is furious with people like them.

In both years Trump won, anti-establishment attitudes were a strong driver of support for him. Understanding where these voters end up in 2026 and 2028 will be key to understanding the outcome of these elections.

Now on to the main event.

Written by Thomas Neuberger. Originally published on God’s Spies

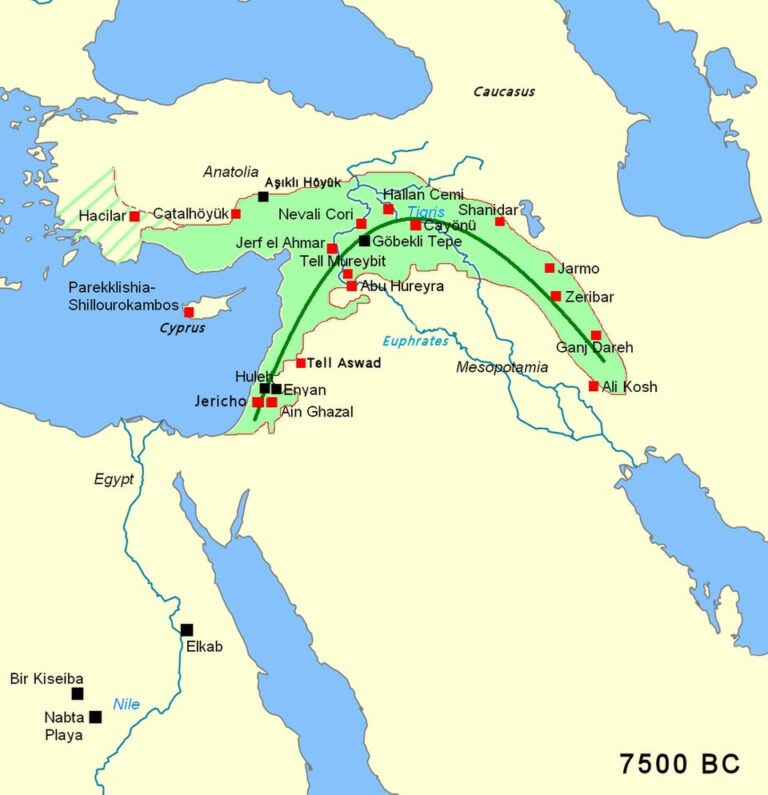

Map of Southwest Asia showing major ruins from before the Pottery Neolithic period c. 7500, “Fertile Crescent” (source). There is no king in these ruins, and one would not appear for another 4500 years.

I’ve been writing a lot lately about political organizations called “states,” commenting on their nature, formation, and goals. These span works as diverse as book club discussions of Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything or James Scott’s Against the Grain.

Simply put, the story goes like this. In one of those articles, I wrote:

Humans have lived in tribal societies for millions of years. These groups, like all human groups, had a structure, but nothing dramatic, no masters and slaves, no workers and kings. There is nothing institutionally compulsory. This hierarchy was mostly benign because it allowed people to leave and take their families and cousins with them. Social life depends more on consensus than on force. There was no coercive state with a monopoly on violence.

For thousands of years, humans lived with agriculture without kings or nations. States emerged only when certain narrow circumstances provided the conditions for their emergence, conditions in which a few people (here referred to as “the few”) could control the workings of the many for their personal benefit.

national history

This is a story about human governance, about how humans are socially organized. The timeline will roughly look like this:

Two million years ago – Homo habilis, especially Homo erectus, lived a tribal life with various governance structures derived from the social lives of various great ape primates, but in Homo erectus’ case, with the addition of greater intelligence. For example, Homo erectus was a master of fire and used fire to reshape the world for the betterment of himself. One could argue that the Anthropocene begins with Homo erectus and fire. 300,000 to 200,000 years ago — Homo sapiens emerges along with other humans. Life in tribes and similar communities continues. Anthropologists like David Graeber have discussed the lives of these tribes (see All Dawns), much of which is inferred from a) the lives of the tribal groups that remain today, and b) descriptions of the lives of non-Europeans encountered by European “explorers”. 12,000 years ago — Human populations living in unique and advantageous areas (mainly near wetlands formed by large deltas) began to realize that they could sustain themselves through a type of natural agriculture, not by fixed-field agriculture per se, but by settling near areas where food could be naturally reproduced. Their lifestyle also includes hunting and gathering, but they are not very mobile. This sedentary lifestyle occurs at different times in different parts of the world. In Mesopotamia, such settlements begin to appear around 10,000 BC.

Life before the state — artist’s rendering (source) Over the next several thousand years, small villages and towns sprang up in these settled areas, ruled without rulers or kings. There are no nations, no dynasties, no conquests of land. After 3,000 BC (5,000 years ago) — Finally, dynastic regions appear in Egypt, Sumer, India, America, and China. That is, states and kings arose in some of these settled areas (not all, just some). As detailed in Against the Grain, special conditions were necessary for the egalitarian forces of tribal and village life to transform into minority rule, the balance of power we know today as the nation-state. Life after the collapse of the state: Farmers harvesting grain for the pharaohs in ancient Egypt (source)

Conclusion:

The nation does not represent an inevitable advance through agriculture. They emerged only when the conditions were ripe for the few to dominate the many, often by controlling the food on which the many depended. For example, a king can take over a town if it relies on grain, an easily stored and hoarded food source. The same cannot be done if the main food is yams, which are resistant to storage and hoarding. States and kings are not the only ways to organize large groups. For example, the Iroquois Confederacy had no king. Non-state societies do not exist to enrich the few, but to benefit the many to the extent that circumstances permit. States do the opposite. The natural state of man is not a life in a state. We humans have lived in nations for just one-eighth of one percent (0.125%) of our time on Earth.

Democracy: A gift from the nation or our beginning?

These ideas lead in several directions. One is the nature of “democracy” as we know it today. Is “democracy” a structure like the one that emerged in the imperial state of Athens? Or is “democracy” not a structure at all, not some kind of state, but a style, a way in which groups decide together? These are not the same thing.

In his provocative essay, “The West Never Was,” David Graeber says:

I began this essay by suggesting that the history of democracy can be written in two very different ways. One could write a history of the word “democracy” starting with ancient Athens, or one could write a history of the kind of egalitarian decision-making procedure that came to be called “democratic” in Athens.

Normally, we tend to think that the two are effectively the same. [T]His argument seems strange. Egalitarian communities have existed throughout human history, and many were far more egalitarian than fifth-century Athens. And each had some procedure for making decisions about issues of collective importance.

Which is actually a more democratic society: a group within the Iroquois Confederacy where people decide together how to use resources, or a state where millions starve to death every year and the king’s choice is either a Democrat supported by wealth or a Republican supported by wealth?

If you found yourself starving outside of the wealth of a few, which group would you prefer to live in?

Rubio’s March of the “Free” West and the “Dominant” West

Another direction this thinking takes us is Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s recent speech at the Security Council in Munich, where he touted “freedom” and “liberal democracy” as Europe’s gift to the world.

It was here in Europe that the idea to plant the seeds of freedom that would change the world was born.

But is the mission of “the West” really to bring freedom to all?

The West continued to expand for five centuries until the end of World War II. Missionaries, pilgrims, soldiers, and explorers crossed the oceans from our shores, settled new continents, and built vast empires that spanned the globe.

Missionaries, soldiers, and a vast empire spanning the globe. Rubio says it was a good thing until things started changing.

But in 1945, for the first time since the time of Columbus, [the West] I had a contract. … Against this background, many people then and now came to believe that the era of Western domination had come to an end and that our future was destined to become a faint and feeble echo of the past.

It was truly an era of Western dominance. Do you see how state-sanctioned “democracy” in the ancient Greek sense is confused with modern-day freedom?

Not libertarian freedom, but freedom itself.

A final note: This is not what I write as a libertarian creed. Every “libertarian” I know wants authoritarian rule from the moment they dabble in it. For these people, freedom is a code for power.

Instead, I write in defense of community life, a communist and socialist life without a state. Not a king. There are no gods. There is no master. It’s just people in the narcissistic group deciding their own lives.

Can we maintain a nation with this? Many say yes, but I agree with Graeber. I don’t think you can do that.

This entry was posted by Yves Smith on February 19, 2026 in Guest Post, Income Inequality, Politics, Social Policy, Social Values.

post navigation

← Coffee Break: Paramount still reaching out to WBD after CBS misjudged Colbert-Talarico interview

Source link