Conor here: What exactly is the end game with farm and food processing workforce?

The Trump administration provided guidance at the end of January when it announced that it will add approximately 65,000 H-2B seasonal guest worker visas for fiscal year 2026—about double from last year. H-2B “guests” work in non-agricultural fields like construction, service industries, and food processing. There is also a push to expand the number of H-2A agricultural guest workers, and the administration already cut their pay last year.

So why is DHS deporting a whole lot of workers only to bring in more foreign workers? Hmm. For one explanation we can look at events last week in Greeley, Colorado.

The largely immigrant union workers at a JBS beef plant there voted Feb 4 to strike over poor working conditions, and it could become the first sanctioned walkout at a major meatpacking plant in decades. Many of the union members are from Haiti and are in the country under temporary protected status, although the administration is fighting to revoke that status and deport them.

The key difference between immigrants like the workers at JBS in Greeley and “guest” workers is that their ability to remain in the country is not tied directly to their employer. That makes them less exploitable, they enjoy minimal protections, and can unionize.

The guest worker program, on the other hand, is often likened to indentured servitude.

Trump himself has a clear preference for these types of workers. From The Hill:

The Trump Organization requested 184 foreign workers to work across various company properties, a record number that has increased over the years.

The company sought to hire workers through H-2A and H-2B visas for temporary positions at Mar-a-Lago, two golf clubs and at Trump Vineyard Estates in Charlottesville, Va., according to data from the Department of Labor.

By Sky Chadde who has covered the agriculture industry for Investigate Midwest since 2019 and spent much of 2020 focused on the crisis of COVID-19 in meatpacking plants, which included collecting and analyzing data on case counts. He also served as the newsroom’s first managing editor, and is now a full-time reporter. Originally published at Investigate Midwest.

Before sunrise in northwestern Oregon in early August, seven farmworkers filed into an aging Ford Econoline van. As they headed toward one of the state’s economic engines, a berry farm, the driver noticed lights flash in his rearview mirror. The passengers murmured their confusion: They weren’t speeding, so why were the cops here? The driver stopped on the side of the two-lane road, near rectangular farm plots. Shouting men surrounded the van. As realization dawned on the passengers, glass sprayed.

After smashing his window, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents pulled the driver out and to the ground. In a later report, used in part to establish probable cause for an arrest, the agents said their unit was searching for the owner of a 2006 Econoline. If the driver was that man, or if the van made an illegal maneuver, the agents didn’t say. Attorneys would later argue the stop was unlawful.

To briefly detain an individual, ICE agents must have a reasonable suspicion based on “specific articulable facts” that a person is engaged in criminal activity or their presence is illegal, according to immigration law. Generally, then, a warrant is required to make an arrest. In the field, agents can access records showing whether detainees have criminal history or pending immigration cases.

ICE saw one passenger had requested asylum. Identified by his initials LJPL in court records, he had fled the men in Guatemala who killed his brother. In early 2024, just across the border in Arizona, he and his 6-year-old daughter had surrendered to Border Patrol, which then released them. As their case wound through immigration court, they’d appeared at every scheduled ICE check-in.

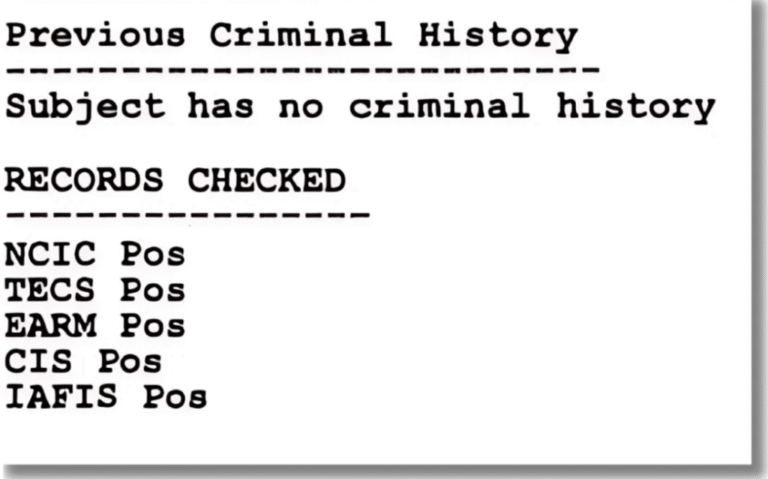

The agents handcuffed LJPL. His partner, who was also in the van, asked the only officer who spoke Spanish what was happening. He told her he was being detained to check his criminal history, she later told attorneys. If he had none, he’d be released, she said the officer conveyed. But the agents already knew what she knew: LJPL had no criminal record.

A screenshot of the I-213 form related to LJPL’s case. DHS agents found he had no criminal record.

Still, ICE did not free him.

Since returning to office last year, the Trump administration has pursued mass deportations across the country, claiming its focus is on hardened criminals. But a review of court records, U.S. Department of Homeland Security documents and interviews show the federal immigration effort has swept up many agricultural workers with no criminal record, often deploying tactics that advocates, lawyers and judges say push the limits of probable cause and due process.

The raids and deportations have not only separated families, many from Latin America, but also further strained farms and meatpacking plants. As the crackdown continues, employers are scrambling to find suitable replacements.

In Oregon, the situation is so desperate that a farm labor contractor recently solicited assistance from an unlikely — and often opposing — source: a farmworker union named PCUN. “The subject line was, ‘Help,’” union president Reyna Lopez said.

The deportation policy has left farmers without a well-trained, knowledgeable workforce. In Wisconsin, dairy farms employ undocumented immigrants for years because they cannot use short-term visa labor. The continuity leads to better production, said Darin Von Ruden, president of the Wisconsin Farmers Union. “Cows are animals of habit,” he said. “If you’re replacing employees on a weekly or even daily basis, it impacts how they produce.”

Recently, after its workers were arrested, a Wisconsin dairy leaned on family members. They took a few days off from their other jobs, which producers are increasingly relying on to stay afloat financially. It quickly proved untenable. “It really became a stressful situation for the whole family,” Von Ruden said. “How do they help make sure the farm stays viable, but also keep their off-farm jobs that they would much rather be doing?”

The administration also cancelled humanitarian parole programs, a move that created more undocumented immigrants and spawned labor shortages at meatpacking plants. Still, neither the administration nor the Republican-controlled Congress have presented a long-term agricultural labor solution. Trump has heralded the H-2A visa program, which brings foreign workers to the U.S. temporarily, but many farmers, including dairy producers, are not eligible. Since Trump took office, lawmakers have not debated or passed legislation allowing more visa workers into the country.

DHS operations in major, Democrat-led cities have caught the country’s attention. Agents have shot and killed several people, including U.S. citizens. Reportedly ordered to fill a quota of 3,000 arrests a day, agents have violated individuals’ constitutional rights, judges have ruled. In Washington, D.C., a judge found agents arrested thousands without establishing probable cause and ended the operation. According to Politico, judges have also largely rejected the administration’s effort to systematically deny bond to most immigrant detainees. A Supreme Court showdown is likely pending after an appeals court ruled in the administration’s favor in early February.

A notable exception fueling detentions is the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision creating so-called “Kavanaugh stops.” A federal judge found DHS arrested Los Angeles residents based on their apparent race and whether they were near construction sites or farms. She issued a temporary restraining order, which an appeals court upheld. But the Supreme Court, with an opinion by Trump appointee Justice Brett Kavanaugh, shot down the restraining order. The case is ongoing.

DHS raids continue throughout farm country, and they show little sign of stopping. Last year, Congress doubled the budget for DHS, which houses ICE and the Border Patrol. Tens of billions of dollars are being spent on reviving shuttered jails and transforming massive warehouses into detention centers. According to the Washington Post, a handful will be built in or near top agricultural states, such as Minnesota, Wisconsin and Indiana.

DHS did not respond to requests for comment.

As Data Shows Otherwise, Trump Administration Claims to Target Criminals

Trump and Kristi Noem, the homeland security secretary, have repeatedly said DHS is targeting the “worst of the worst.” In January, as polls showed more and more Americans souring on the department’s actions, Trump again tried to sell the public on mass deportation. In a Truth Social post, he said DHS “must start talking about the murderers and other criminals that they are capturing. … Show the Numbers, Names, and Faces of the violent criminals, and show them NOW.”

But immigration violations are civil matters, and criminal allegations don’t matter in immigration court. “It’s not out of the ordinary for DHS to allege things and then never bring forward charges,” said Veronica Cardenas, a DHS counsel between 2010 and 2023 who now runs her own law firm defending immigrants in New Jersey. “In immigration court, the rules of evidence don’t apply.”

DHS’s own data shows about three-quarters of current detainees have no criminal record. “If they’re taking more workers who have no allegations against them, then what are they really there for? What is their real intent?” said Aissa Olivarez, an attorney with the Madison-based Community Immigration Law Center. “I think really it’s to create a spectacle and an example.”

Max Morales, a Vermont farmworker, experienced the cognitive dissonance firsthand. After Border Patrol raided the dairy farm where he lived and worked last year, DHS shipped him to a Texas detention center. He worried who he might encounter, but, as he swapped stories with his fellow detainees, he quickly realized most were like him: No criminal record, just trying to make a living. In paperwork DHS filed in his immigration case, the department listed his criminal history as “none.”

“Very few people I talked to had any run-ins with the law at all,” Morales said in Spanish through an interpreter. “That’s not who was in that detention center. For all of us, it felt unjust. None had done anything leading up to our detention. We were all just caught up in the system together.”

A screenshot of the I-213 form related to the workers arrested in the Vermont raid. DHS agents use the form to show probable cause or reasonable suspicion and to justify a deportation. All eight of the arrested workers had no criminal history.

A similar situation occurred at a local jail in Nebraska. This past summer, DHS agents raided Glenn Valley Foods, an Omaha beef processing plant. DHS said the raid “revealed massive identity theft,” though leadership focused on a man who, after trying to hide from agents in the ceiling, allegedly brandished a weapon.

“If you’re here illegally, you’ve already broken the law,” said Todd Lyons, ICE’s acting director. “When you break the law by coming here illegally and then threaten and assault federal officers on top of that — you’re a threat, plain and simple.”

ICE placed about 60 workers in the Lincoln County jail, which is roughly four hours west of Omaha. Ultimately, federal prosecutors charged one detainee with identity theft. For others facing “administrative identity theft violations,” ICE let their cases be “resolved in immigration court,” the U.S. Attorney’s Office for Nebraska said in a statement.

The jail is overseen by Sheriff Jerome Kramer, a Republican. The county voted overwhelmingly for Trump each time he ran for president, and Kramer has run unopposed for county sheriff five times since 2006. He “couldn’t quite get my head wrapped around” why the Glenn Valley workers were in his jail, he said.

Lincoln County, Nebraska Sheriff Jerome Kramer and TinaMarie Fernandez (left), the leader of a bilingual advocacy organization at the Lincoln County jail on Tuesday, January 20, 2026. Sheriff Kramer had invited Fernandez to assist detainees from an ICE raid in Omaha who were sent to the rural county. photo by Keith Howe, for Investigate Midwest

“They’ve never broken the law,” he said. “They’ve worked here for 20 years, 30 years, and they’ve raised their families here. Why are they being locked up just for providing for their families?”

The Biden administration said “the border’s open and laid out red carpets,” Kramer said. Maybe a process was skipped, but the individuals had come for a reason. “Yeah, the paperwork is not done correctly or never was finished, but instead of going to all this expense and upending lives and tearing families apart, why don’t we just get somebody to help them with their damn paperwork?

“Get it filled out right and get them back to work,” he continued. “Let them feed their families. That’s all they ever wanted to do anyway. They didn’t come here to hurt anybody. They took up jobs that some other lazy white guy didn’t want.”

On a Long Ignored Farm, a ‘Concerned Citizen’ Cries Human Trafficking

“Immigration is here!”

As three Border Patrol vehicles drove onto the Vermont dairy farm in April, Morales ran for a collection of red barns. The farm was a 10-minute drive from the Canadian border, and Morales regularly saw the agency’s white-and-green trucks on the nearby roads. But in his eight years working there, he’d never seen agents enter the property, much less chase after its employees.

Months into the second Trump presidency, DHS was ramping up its enforcement on farms. In the Vermont raid, the state’s largest in recent memory, eight farmworkers with no criminal record were arrested. The operation was, ostensibly, about human trafficking.

It began with a tip from a “concerned citizen,” according to a summary of the raid filed in the detained workers’ immigration cases. The tip alleged multiple men were in the woods near the farm. The area “is actively being used to facilitate human smuggling,” agents wrote in the summary. “Multiple groups” had been apprehended in “prior weeks.”

The summary does not say when the call was placed. “They basically used the fact that there was at some point a call about suspicious activity to pull up to this farm that they had passed many, many times before,” said Brett Stokes, the director of the Center for Justice Reform Clinic at Vermont Law and Graduate School, who represented Morales and his coworkers.

Morales’ employer, Pleasant Valley Farms, declined to comment.

After hiding in a barn, Morales ran to his trailer. Soon, with agents surrounding the trailer, his employer ordered him and his other coworkers out. When he complied, they arrested him and confiscated his belongings, he said.

He wasn’t asked any questions. “At no point did they say, you’re being detained for this reason or that reason,” he said. The agents then transported him to a nearby Border Patrol station. Only there, he said, was he asked where he was from and how long he’d lived in the country. In their summary, agents noted they ascertained he entered the U.S. from Mexico in 2016.

Within 100 miles of the U.S. border, Border Patrol agents can arrest suspects if there is “reasonable suspicion” they just crossed the border — essentially catching them in the act. The requirement is a less stringent legal standard than “probable cause” but it must be more than a hunch, according to the ACLU.

“I feel like the reason that they stated all this, ‘It’s being used to facilitate human smuggling,’ is they needed reasonable suspicion to maybe speak to him,” said Cardenas, the former DHS attorney. “Then once he said he was not born in the U.S., then that gives them probable cause for the arrest.”

A branch of DHS named Homeland Security Investigations investigates trafficking cases, Cardenas said, and typically it would want to interview potential participants. “If it’s a known human smuggling spot, I would hope that they would be investigating to make sure they’re arresting who they need to arrest,” she said. Morales said no agents asked him about criminal activity.

DHS did not return requests for comment about whether a human trafficking investigation had been opened. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for Vermont, in charge of federal indictments in the state, declined to say whether charges related to the raid had been filed and referred Investigate Midwest to Border Patrol. Its parent agency, Customs and Border Protection, did not respond to a request for comment.

Following two weeks in a Vermont prison, DHS moved Morales to a Texas detention center. After about a week, Stokes secured his release on bond. A judge had agreed he wasn’t a threat to the community or a flight risk. When he returned to Vermont, he exited the plane still wearing his work clothes, a bright orange shirt and camouflage cargo pants.

Once back, he learned what happened to the others. Four had been deported within weeks of the raid — “unheard of” speed, Stokes said. They were subject to the Trump administration’s expedited removal policy, which advocacy groups argue violates immigrants’ due process rights. In August, a federal judge temporarily blocked the policy, and the case is ongoing. Two others, including Morales’ brother, were also deported eventually. His brother was dropped off in Mexico in his work clothes and no belongings. “It’s not how you want to go back to your country,” Morales said.

Morales returned to working on a dairy farm. It’s a payday no matter the weather, he said. If it rains or snows, construction workers are out of luck. But he also worries about immigration agents arresting him again. He knows others have left the dairy industry. The fear is especially acute for those who don’t live on farms and have to traverse the roads to job sites, he said. The risk of an encounter with federal agents is high.

“It happened once,” Morales said. “It could happen again.”

Invoking 9/11 to Keep Meatpacking Plant Workers in Jail

About 60 immigrants lined up outside the county jail in the heart of North Platte, Nebraska, and waited their turn for processing. Visibly anxious, they were in days-old work clothes, handcuffed and with chains across their waists. One mother was the primary caregiver for a teenage daughter and an autistic son, and she had not been able to contact them for days.

ICE had arrested the immigrants during a June 10 raid on the Glenn Valley Foods beef processing facility in Omaha. Many now faced interminable detentions as the Trump administration tried a new approach to keeping immigrants locked up: invoking a rarely used policy instituted after 9/11.

Beyond interrupting the lives of working parents, the raid punched a hole in Glenn Valley’s production. With few remaining workers, it dropped by almost two-thirds, The New York Times reported in July. “We’re building back up from ground zero,” the owner, Gary Rohwer, said. He could not be reached for comment.

As Rohwer’s workers waited in line, they snacked on jerky and bananas. Kramer, the county sheriff, had invited a local advocacy organization, HOPE Esperanza, to interpret for his deputies, and HOPE’s volunteers had brought the food. Kramer’s puppy, a rambunctious Blue Heeler cross named Connor, zipped through detainees’ legs and demanded jerky bites. It helped relieve some tension.

Once inside, the women detainees were kept together, but the men were placed with the jail’s general population. Partly due to the language barrier, some men experienced threats, said TinaMaria Fernandez, HOPE’s founder and executive director. “There were some clear safety issues,” she said.

Kramer agreed and relocated the men. “We got U.S. citizens in here,” he said. “They’re bad criminals.” Some had been accused of sexual assault, he said. In contrast, according to the Omaha World-Herald, a handful of the Glenn Valley workers had traffic infractions.

Within days, about nine detainees were deported. They had signed paperwork, all in English, and showed it to the HOPE volunteers. “They didn’t even know what it said,” Fernandez said. “They were told they needed to sign, and it would make this whole process easier. We had to break it to them this was a deportation letter.”

But some found freedom. In the month following the raid, Iowa-based, all-volunteer organization Prairielands Freedom Fund posted the bond for 17 detainees. The cases were straightforward, said Julia Zalenski, the fund’s founder. In her nine years running Prairielands, immigrants like the Glenn Valley Foods detainees would normally qualify for bond, she said. Most had no criminal history, and they had lived in the U.S. for decades. Typically, a judge would release such defendants while their immigration cases proceeded.

On July 8, the typical process was upended.

Two days later, Prairielands attempted to pay bond for several detainees, but ICE denied them all, Zalenski said. It quickly dawned on her and her team: “This is not about one person,” she said they started to think. “This is a system change.” The cases were exactly the same, other than the day the bond was posted, she said. Prairielands tried to explain the situation to frantic family members so “it wasn’t this horrible, cruel thing that was happening for absolutely no discernible reason,” Zalenski said. “Which, it was.” (DHS did not respond to requests for comment.)

The Trump administration had altered the longtime policy governing bond for detained immigrants. It decided most immigrants were subject to an “automatic stay.” This meant that even if a judge decided an immigrant qualified for bond, ICE could keep them imprisoned. It was rarely invoked, but the stay had been on the books for more than 20 years, instituted a month after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It now applied to mothers with no criminal record.

One was Maria Reynosa Jacinto, a U.S. resident for more than 20 years with an adult daughter. A week after the policy change, a judge granted her a bond of $9,000. Prairielands paid it through ICE’s online portal, but it was denied, according to court records. Three days later, Prairielands tried again. ICE denied it again. The group tried once more a week later — same result. ICE gave different reasons each time but never mentioned the new policy, Zalenski said.

The ACLU of Nebraska sued on Reynosa Jacinto’s behalf in federal court. On Aug. 19, a judge ruled that her detention was unlawful and ordered her released. The ACLU of Nebraska declined to make their client available for an interview. Like most of the detainees, she was not charged with a federal crime.

While some families were reunited, others were torn apart. One young man detained in the jail had a pregnant fiancée. He had signed a document authorizing his deportation, and, during his phone call, they decided she would remain in the U.S. so their child could have a better life. After hanging up, he hugged Fernandez, then crumpled to his knees sobbing. “There’s nothing you can say in that moment,” she said.

After the encounter, Fernandez turned to a colleague. A longtime nurse, she’d witnessed many traumatic moments, but this one was striking. “That was like holding the hand of someone dying,” she remembered saying. “But worse … because their life as they know it is over.”

Farmworker Clients Held ‘Incommunicado’ as They Move Through DHS Detention System

Around 10 a.m. last August, hours after the Oregon farmworker LJPL was arrested, his attorney arrived at ICE’s Portland office. LJPL’s partner had contacted her and told her what happened. The attorney regularly visited the facility to meet with clients, but, this morning, a security guard stopped her.

Representing ICE detainees has always been challenging, but now just accessing clients in the system is a struggle, said Tess Hellgren, an attorney at the Portland-based Innovation Law Lab, which represented LJPL and other detained farmworkers. One client was ultimately discovered in Guantanamo Bay. In another instance, law lab attorneys met with an arrested farmworker for 15 minutes before an ICE agent said to wrap it up. When they asked for more time, the agent said “sixty seconds.”

“What is striking now,” Hellgren said, “is the extent to which access is being obstructed by holding clients really effectively incommunicado.”

The security guard told LJPL’s attorney, Kathleen Pritchard, she needed a signed G-28 form, an official document showing he agreed to her representation. ICE’s standards state detainees are allowed to “meet privately with … prospective legal representatives.” Pritchard asked for an ICE officer.

The guard returned a few minutes later. No one will speak with you, the guard said, according to an affidavit she later made in LJPL’s court case. The guard handed her a Post-It note with phone numbers for ICE liaisons she could call. She waited two more hours but wasn’t allowed in. According to court records, LJPL was sitting inside.

Two days later, he called Pritchard from a detention facility in Washington state. He told her he wasn’t asked if he wanted an attorney, and agents presented him with documents he didn’t understand. He declined to sign them, worried he would “get tricked into signing for my deportation,” he later told attorneys.

The law lab filed a habeas corpus petition on his behalf. With a pending asylum case — he feared his brother’s murderers were targeting him — and having appeared at every ICE check-in, he deserved to be freed, his attorneys argued. However, the judge found LJPL had a removal order from a previous border crossing. Even though DHS released him after he entered again in 2024, the removal order made his presence illegal. The judge ruled his continued detention was lawful.

But the judge also ordered DHS to quickly conduct a reasonable fear interview. Part of the asylum process, the interview seeks to establish whether someone is fleeing persecution. When ICE contacted him for the interview, the agency would not allow his lawyer to be present, according to court records. Desperate, he declined the interview. He no longer could stand the “ongoing nightmare” of being detained.

In mid-September, several weeks after his arrest, DHS moved him to Fort Bliss, a giant tent city in Texas. The Washington Post found the detention center failed to treat medical conditions, to keep detainees safe and to allow them access to attorneys. Days after arriving, guards placed him on a flight to Guatemala. But, during a stop in El Salvador, he was told there’d been a “mistake.” He was flown back to Texas.

The issue stemmed from a clerical issue. All documented immigrants have an alien registration number, which is a form of identification. LJPL had an A-number from a previous deportation. However, when he reentered the U.S. in 2024, ICE assigned him a second A-number, the one associated with his asylum case. In court documents, ICE said once an officer recognized the error, it worked quickly to return LJPL to the U.S.

Then, several days later, guards woke him around 3 a.m. and placed him on another plane. He understood he was being deported again. “I started to cry and I almost fainted,” he later told attorneys. “I felt terrified and uncertain about what was going to happen to me.”

But when the plane landed, he was back in Washington state, at an ICE processing center. He was told he had “two cases” a judge had to sort through. With a consistent pain in his chest, he asked to see a physician. “The doctor told me the pain is likely related to trauma and anxiety I have from feeling so helpless,” he told his attorneys. The doctor gave him ibuprofen.

Based on the aborted deportation, LJPL’s attorneys argued DHS knew he should not be detained, according to court records. They again asked for his release. The judge denied the request in late October, about three months since what his attorneys argued was an illegal arrest. The judge again ordered a reasonable fear interview.

Hellgren, citing his privacy, declined to say whether he was eventually released or was deported. In court records, he described his despair throughout his experience, especially with not knowing whether he would see his partner and daughter again.

“I do not understand what is going on and why I am being moved around,” he said. “It is really hard for me to be away from my family.”