Eve, here. The German finance minister’s statement makes clear that the EU, which has previously had strong provisions to protect the interests of small countries, intends to operate on a model where “some animals are more equal than others”.

Andrew Korybko is a Moscow-based American political analyst specializing in the global systemic transition to multipolarity in the new Cold War. He holds a doctorate from MGIMO, which is affiliated with the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Originally published on his website

Poland’s role is crucial as it could make or break these plans.

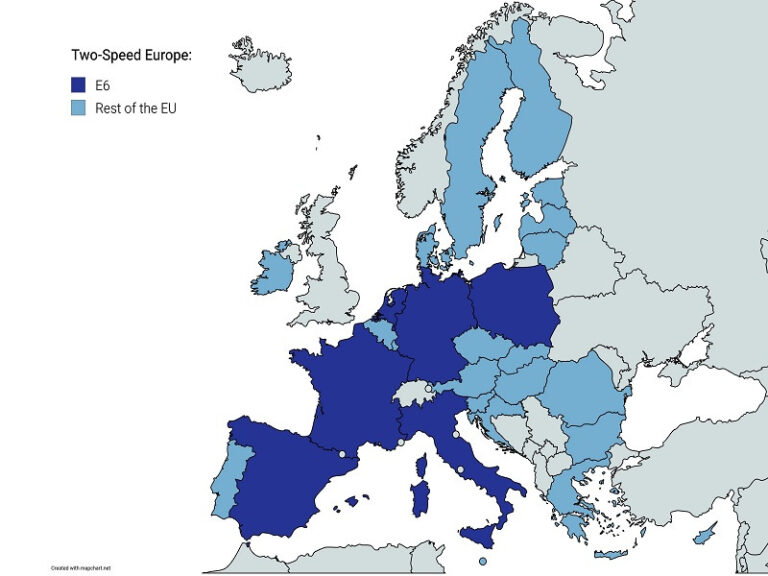

German Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil recently declared: “Now is the time to make Europe twice as fast. Germany, together with France and other partners, will therefore now take the lead in making Europe stronger and more independent. As Europe’s six largest economies, we can now be the driving force.” These two exclusive tiers also include Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Poland. The goal is to optimize decision-making by circumventing EU agreement requirements.

According to the Washington Post, Mr. Klingbeil also sent a letter to his countries’ partners, stating that he would prioritize “creating savings and investment cooperatives to improve financing conditions for businesses, strengthening the role of the euro as an international currency, strengthening cooperation on defense spending, and ensuring resilient supply chains for critical raw materials.” His “Two-Speed Europe” proposal essentially functions as an adaptation of the EU to great power geopolitics.

President Trump brought this approach back to the forefront of international relations after approving the detention of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the seizure of a Russian-flagged tanker in the Atlantic Ocean. The summation that major powers are prioritizing their national interests, no longer concerned with accusations of violations of international law, bodes ill for the EU’s interests. After all, the US currently wants Greenland, a territory of Denmark, an EU member state, and even if the US really wanted it, the EU could not stop the US.

A new awareness of the EU’s powerlessness has been building for some time, particularly last summer, when President Trump’s tariff threats forced the bloc to agree to a lopsided trade deal with the United States, seemingly prompting Germany’s de facto leader to finally take action to correct it to some extent. Indeed, the EU will probably never be able to regain its “strategic autonomy” vis-a-vis the US, but there is still potential for it to work more cohesively to improve its competitiveness on the world stage.

For that to happen, member states would have to surrender some of their sovereignty to Brussels, furthering Germany’s long-standing goal of federalizing the EU under its de facto leadership. This goal is being pursued through multiple means, including the EU’s planned transition to a military union and the creation of a larger common debt pool through increased financing for Ukraine. The problem is that such important decisions require EU agreement, which small states like Hungary can block.

It is important for Germany to bring together an exclusive layer of EU member states to make such decisions among themselves, and then use the momentum unleashed by producing concrete facts on the ground to force smaller member states to follow suit. The clock is ticking, as Poland’s ruling coalition of liberals and globalists could be replaced by a coalition of conservatives and populists after the next parliamentary elections in autumn 2027, which is why Germany wants to get as much done as quickly as possible.

Those plans could be blocked before then if Poland’s conservative president vetoes the relevant legislation. That’s because the ruling coalition of liberals and globalists lacks the two-thirds majority to overturn the president. The move by this exclusive layer, which does not require legislative approval to advance the EU’s de facto federalization, could also be challenged by Poland’s Constitutional Court and Supreme Court, which are at the center of a highly partisan dispute, potentially delaying implementation until the next election.

Poland’s role in this German-proposed process is crucial. Participation and tangible progress could create facts on the ground that would be difficult to reverse, even if there is a change of government after fall 2027. Similarly, resistance through the above-mentioned means may impede the aforementioned progress and avoid its attendant consequences. If a coalition of conservatives and populists comes to power in Poland, it could mobilize regional allies to collectively oppose these plans more effectively.

In that scenario, the EU would be divided into two tiers, led by Germany and led by Poland, with the first representing the traditional member states and the second representing the new member states. Just as the German-led league plans to make its own decisions and force its smaller peers to follow suit, the Polish-led league could do the same for its larger peers. These dynamics could effectively result in the EU disintegrating into two distinct blocs that maintain unity only through inherited policies such as freedom of movement.

It is therefore ironic that Germany sees its “two-speed Europe” proposal as an adaptation to great power geopolitics that would allow the EU to work more cohesively in order to increase its competitiveness on the world stage, when this proposal actually risks fatally damaging the current EU. The odds remain in Germany’s favor, but that could change decisively after Poland’s next parliamentary elections in autumn 2027, which are shaping up to have repercussions across the continent.