Eve is here. While it would be unusual to portray “shock and awe” sanctions as a cause of depositor concern and action, increasing funding costs for many European banks, this article has some very important findings. This shows that the hike of around 60 basis points was meaningful and, of course, led to tightening of lending by banks that were “at risk.”

Written by Falco Fecht, Head of Research at Deutsche Bundesbank. Professor of Financial Economics at Frankfurt School of Financial Management. Stefan Gleppmeier, Research Economist at Deutsche Bundesbank. and Björn Imbierovich, economist at Deutsche Bundesbank. Originally published on VoxEU

Discussions about the economic impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have focused on supply-side concerns such as rising energy prices and disrupted supply chains. However, this overlooks the role of the financial sector. This column uses detailed trade data to show that the outbreak of war acted as a “quiet monetary tightening.” Banks in crisis face an immediate increase in funding costs and a reduction in the supply of credit, which would have had the effect of raising interest rates by nearly 60 basis points well before the ECB took action. Geopolitical tensions appear to be influencing both the stance and effectiveness of monetary policy more directly and more strongly than previously assumed.

Geopolitical tensions are once again taking center stage in macroeconomic policy discussions. From Russia’s continued war in Ukraine to instability in the Middle East, disruption to Red Sea transportation, US involvement in Venezuela, and new trade disputes, the global economy faces a new era of fragmentation. Since the Russian invasion in February 2022, the dominant economic discourse has focused almost exclusively on supply-side pressures. Rising energy prices, supply chain disruptions, and the resulting cost-push inflation.

These physical disruptions are well-documented, ranging from the fundamental rewiring of Europe’s import structure (Felbermayr et al. 2025, Borin et al. 2023) to the complex supply chain coordination of neutral countries (Li et al. 2024). However, while these studies capture the staggering real economic costs (Gorodnichenko and Vasudevan 2025), they largely abstract away the concurrent shock, namely the tightening of bank funding conditions. Given this purely supply-side diagnosis, early discussions among central bankers focused on the extent to which these price spikes should be “spotted” while preventing second-order effects.

However, this perspective overlooks an important transmission channel: the financial sector. As the IMF and others have warned of “geoeconomic fragmentation” (Gopinath et al. 2025), it is important to understand how these disruptions affect not only trade flows but also bank balance sheets and, therefore, aggregate demand. A recent paper (Fecht et al. 2026) argues that geopolitical shocks reshape the macroeconomy long before central banks decide to act.

Using detailed European data from corporate deposit and loan transactions, we show that the Russian invasion caused a direct balance sheet shock to at-risk banks. This shock not only caused local stress; It raised financing costs, reduced the supply of credit and compressed aggregate demand. In effect, this invasion acted as a “quiet tightening” of financial conditions, amplifying the impact of subsequent ECB rate hike cycles. In other words, geopolitics acted as a financial shock.

Depositors as the first line of monitoring

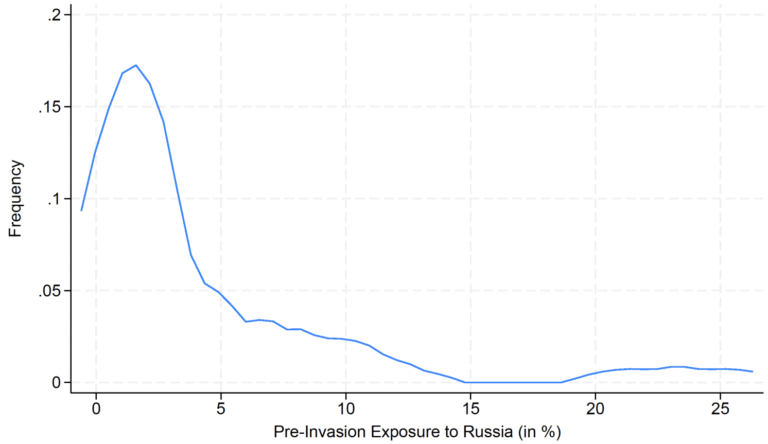

The sanctions, which were significantly expanded in February 2022, effectively stranded the assets of European banks with borrowers in Russia and Belarus. 1 Although the median exposure of affected banks was manageable, amounting to approximately 1.5% of capital, the shock immediately increased the perception of bank risk. Figure 1 shows the distribution of banks’ exposure to Russian and Belarusian borrowers before the invasion. The data reveal significant heterogeneity. While many institutions had limited direct contact, relevant parts of the distribution held substantial exposures relative to their capital. These existing financial connections served as a conduit for geopolitical escalation to lead to immediate funding constraints.

Figure 1 Banks’ average exposure to Russian and Belarusian borrowers before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022

Note: This figure shows kernel density estimates of banks’ pre-invasion exposures to Russian and Belarusian borrowers. Exposure is defined as the sum of outstanding loans and bonds to Russian and Belarusian companies, scaled by the bank’s book capital (2021 average). The sample is restricted to banks with positive exposures that report to both the AnaCredit and SHS databases. Data sources: AnaCredit, SHS-G, SHS-Base Plus.

Unlike insured individual depositors, large corporate depositors are sophisticated, uninsured, and highly mobile. They keep a close watch and respond quickly when risks materialize and the bank’s financial health is called into question. Our analysis reveals that immediately after a breach, exposed banks face clear funding penalties.

We find that exposed banks need to offer approximately 5 basis points higher interest rates to hold non-financial corporate deposits compared to unexposed banks. In an environment where interest rates remained negative, this was economically significant and represented a 15% increase compared to the market spread at the time. By employing a precise identification strategy and comparing deposits of the same firm across different banks on the same day, we can isolate this bank-specific component of funding stress. Beyond pricing, there were also volume constraints. Deposit flows have weakened, significantly reducing the likelihood that exposed banks will receive new corporate funding.

For the banking sector as a whole, this was no small friction. We estimate that this shock increased deposit funding costs for exposed banks by between €80 million and €110 million in total. Looking at this from a financial conditions perspective, this “quiet tightening” effectively acted like an additional 57 basis point hike in policy rates for at-risk banks. Importantly, this tightening came months before the ECB officially raised interest rates from -0.5%.

Debt-driven credit crunch

Basic financial theory suggests that when banks face rising funding costs and declining net assets, they will wind down their operations. Our findings confirm that this cash crunch is directly linked to a contraction in loan supply.

We find that banks with exposure experienced a decrease in credit volume of approximately 3% compared to banks without exposure. Using loan-level data from AnaCredit, we again compare the same borrowers across different lenders to control for loan demand.

Importantly, it establishes a direct cause-and-effect relationship between both sides of the balance sheet. The banks whose deposit costs rose most sharply in the immediate aftermath of the invasion were also the ones that cut lending the most in the months that followed. This confirms a typical “debt-driven credit crunch.” It’s not just that banks had bad assets. In fact, geopolitical shocks worsened refinancing conditions, and these constraints spilled over into the real economy.

This is important for the economy as a whole. This is because borrowers cannot completely replace this decrease in loan supply with credit from other banks, leading to a decrease in total borrowings and a shift in investment activity. This represents a clear demand-side contraction. While energy markets are pushing up inflation (supply shock), banking channels are quietly suppressing investment and consumption (demand shock), complicating the situation for monetary policy makers.

expansion of monetary policy

Perhaps the most important implication for current policy is what happens next. When the ECB started raising interest rates in July 2022, the banking sector was already “scarred.”

We found that this existing weakness significantly changed the way monetary policy tightening was communicated. Banks hit by geopolitical shocks communicated subsequent rate hikes much more forcefully than their peers.

Local projection results show clear differences.

With the policy rate raised by 1 percentage point, exposed banks raised their deposit rates by about 40 basis points more than unexposed banks. The same policy shock caused lending rates to rise by another 25-30 basis points.

This amplification is consistent with the theory of state-dependent external financial rewards (e.g., He and Krishnamurthy 2013). Financially challenged banks have less ability to cushion interest rate shocks. Costs must be passed on to protect margins and preserve capital. As a result, a “geopolitical wedge” in bank balance sheets served to drive ECB policy. The effective stance of monetary policy has been tighter than what headline interest rates imply for most businesses and households.

Impact on a fragmented world

Our findings cast doubt on the view that central banks can simply “see through” geopolitical events as temporary supply distortions.

First, geopolitical shocks are not purely supply shocks. While energy prices dominate headline inflation, the banking channel creates an offsetting contraction in demand. If we ignore this mechanism, we risk misjudging the fundamental stance of monetary policy.

Second, policymakers must consider the “tightening shadow” caused by geopolitical events. In the case of the Ukraine invasion, at-risk banks faced additional funding cost burdens equivalent to a 57 basis point rate hike before the first official rate hike. Central banks operating in a fragmented global economy need to monitor these endogenous tightening effects to avoid excessive tightening that weakens the economy.

Our findings therefore expand our understanding of the economic costs of war. Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2023) warned early on that aggression could threaten global financial stability through a loss of trust, and we quantify this mechanism specifically for European banks’ balance sheets. War not only affects economies through physical destruction and collateral damage, as documented by Shpak et al. (2023) is aimed at Ukrainian companies, but it also applies through cross-border channels of transmission that suppress lending in Europe, even in the absence of direct physical damage.

Third, monetary transmission becomes stronger when banks are financially constrained. Rate hikes carried out in the shadow of a geopolitical crisis could have a stronger and faster impact than standard models predict.

Finally, it highlights the intersection of macroprudential and monetary policy. Supervisors need to incorporate geopolitical concentration risks into stress testing and capital planning. As our results show, banks with large exposures to geopolitically sensitive borrowers act as conduits, transmitting foreign policy shocks directly to domestic credit conditions.

In an era of increasing geopolitical fragmentation, the boundaries between foreign policy and financial policy are eroding. Geopolitical shocks affect not only the supply side of the economy, but also the strength of monetary transmission through the banking system. Understanding this bank lending channel is no longer just a question of financial stability. This is essential for coordinating monetary policy in a world where geopolitical risks increasingly dictate macroeconomic outcomes.

____________

https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/12/22/russia-s-war-of-aggression-against-ukraine-council-extends-economic-sanctions-for-a-further-6-months/

See original post for reference