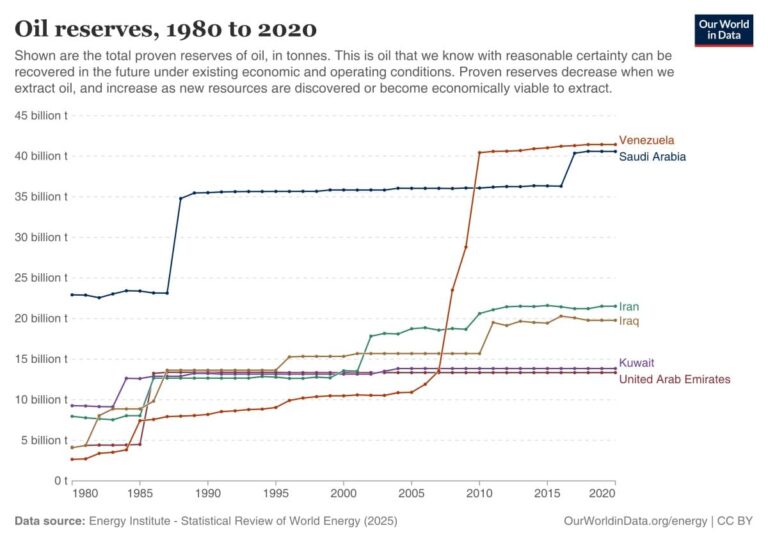

Eve is here. This high-level post usefully debunks President Trump’s deceptive doctrine regarding Venezuelan oil. It also includes a chart documenting a point previously made here: that many oil-producing countries, including Venezuela, have suddenly increased the level of proven reserves they claim despite the absence of new discoveries.

Kurt Cobb is a freelance writer and communications consultant who frequently writes about energy and the environment. His work has also appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Resilience, Le Monde Diplomatique, TalkMarkets, Investing.com, Business Insider, and many other outlets. First appearance: OilPrice

Most of Venezuela’s reported oil reserves are unaudited government claims that ignore economic viability. Most of the country’s oil is very heavy crude, which requires expensive upgrading, diluents and persistently high prices to produce profitably. Political instability and long-term investment risks make it unlikely that Venezuela’s oil production will increase significantly in the short term.

In the wake of the Trump administration’s push for war and blockade against Venezuela, and its promise to significantly increase the country’s oil production, it’s worth knowing why the claim that Venezuela has the world’s largest oil “reserves” is a problem. It is also important to understand what this means for the future of Venezuelan oil production.

Consider the following:

1. Official oil reserves are just that. These are numbers reported by official government sources. When these numbers come from large national oil companies, as in the case of Venezuela, they are rarely verified through independent audits. And these numbers tell us nothing about the economic viability of the claimed reserves.

2. Some OPEC countries, including Venezuela, have a pattern of suddenly claiming large increases in oil reserves without evidence of additional economically viable discoveries. To be clear, reserves are known mineral deposits that can be extracted using current technology and have proven profitable at current prices. The term “reserves” does not seem to apply to most of Venezuela’s extra-heavy crude oil at current prices, which is believed to be 90 percent of estimated reserves. This is especially true when facility upgrades need to be built from scratch. Venezuela has only one very heavy crude oil facility, which began production in 1947. Such high-value long-term investments require belief that prices will reach and sustain much higher levels than they currently are, and that political and social conditions will remain calm and favorable for an extended period of time. (See this infographic for a comparison of Venezuelan crude oil with global crude oil.)

In several countries in the Middle East, the sudden increase in reserves described above occurred in the mid-1980s. In Venezuela, it occurred over a three-year period from 2007 to 2010. The following graph is based on the World Energy Statistics Survey (previously sponsored by oil giant BP, but now published by an independent organization).

3. Most of Venezuela’s so-called reserves exist in the form of very heavy crude oil in a region called the Orinoco Belt in eastern Venezuela along the Orinoco River. Venezuela’s National Oil Company claimed in 1998 that the region contained 270 billion barrels of extra-heavy crude oil, according to a report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Venezuela today reported 303 billion barrels of reserves of all types, including heavy crude oil, which it currently processes and sells. But no one knows the actual numbers because there is no external, independent audit.

4. Extra-heavy crude oil is a very viscous liquid, about the consistency of “cold peanut butter,” making it suitable for use in asphalt but little else. Before it can be used as oil, it must be upgraded using complex and costly processing, which requires vast quantities of natural gas and diluents such as naphtha, which are mixed with the oil to enable transport in pipelines. Steam and water injection is required just to extract heavy oil from underground. Also, during refining, the refining cost is high because the sulfur content is high and sulfur is an air pollutant that needs to be removed. In other words, it takes a huge amount of energy to extract and process ultra-heavy crude oil into what we call oil. And they’re all pretty expensive.

5. This brings us to the price of oil and the economics of producing very heavy crude oil in Venezuela. The global benchmark for crude oil is Brent crude, currently trading at about $64 per barrel. But Venezuela’s extra-heavy crude oil is so difficult to refine that it sells for between $12 and $20, a steep discount to the world standard price. The cost of diluent adds an additional $15 to the cost of running this extra-heavy crude through the pipeline.

So sellers are already taking a financial haircut of $27 to $35 compared to global benchmark crude oil. For large-scale investments to be made in Venezuela, world oil prices would likely need to hover around $100 a barrel for many years to force oil companies to risk the kinds of investments that only pay off in 20 to 30 years, such as those needed to extract and refine very heavy oil.

6. All of this suggests that Venezuela’s oil production probably won’t increase much in the coming years. And since producing most of Venezuela’s oil resources requires much higher prices, the idea that increased Venezuelan oil production could lower current oil prices is nothing short of ridiculous.

Of course, that doesn’t take into account the political and social instability plaguing Venezuela following the U.S. attack and blockade. I also don’t take into account the fact that even though Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has been removed from office, the vice president (now elevated to acting president) and government are still in power. These are the same people who previously expropriated the assets of domestic US oil companies and imposed high taxes on the remaining oil operations. Given this background, it is unlikely that there will be much foreign investment in Venezuela’s oil industry in the near future.

The slapstick diplomacy that the United States is currently engaging in with Venezuela may appear to somehow free up Venezuela’s supposed oil resources. But all it will do is prove that wealth is as elusive as ever.