Eve, here. I spent a full day attending an Explorers Club presentation on the results of field research during the 2007-2008 International Polar Year. The club’s members were made up of adventurers and scientists, many of whom had spent long periods in the Arctic. It was clear to humans that they were seeing widespread and alarming evidence on a global scale. However, many conveyed their love for the region’s harsh beauty.

Written by Emily Cattaneo, a New England author and journalist whose work has appeared in Slate, NPR, The Baffler, Atlas Obscura, and elsewhere. Originally published in Undark

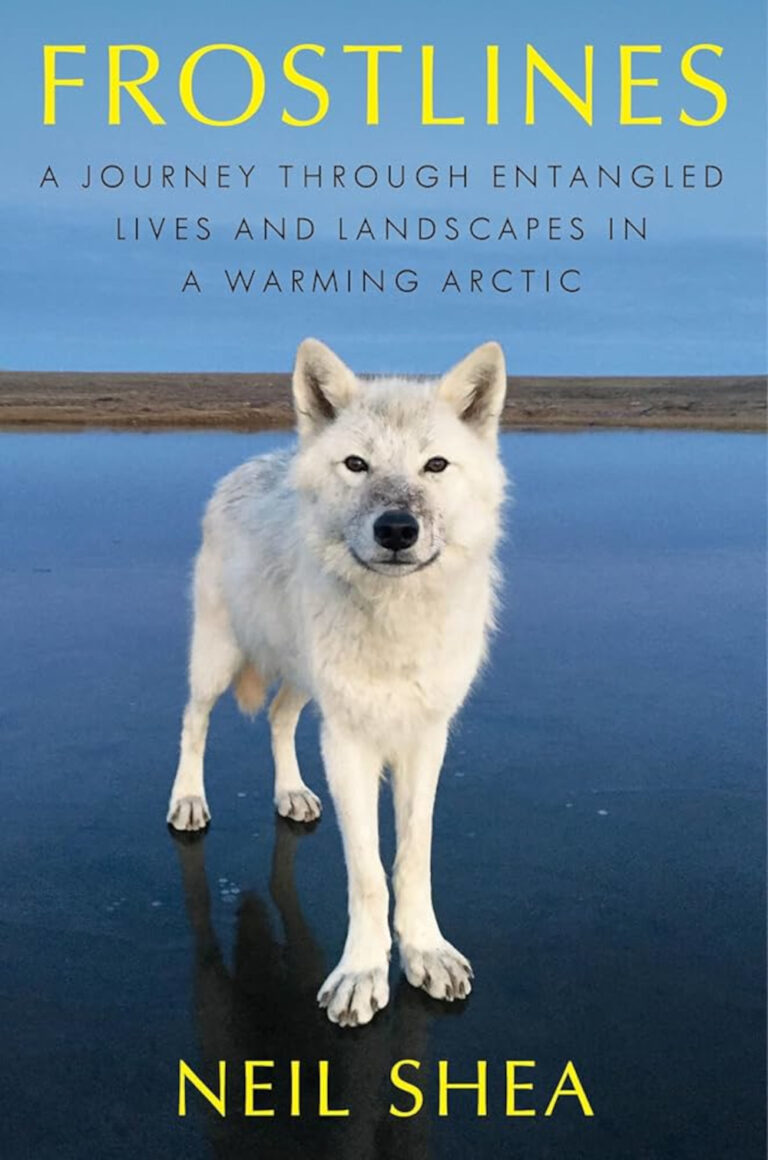

Neal Shea never expected a wolf to invade his tent. It happened while Shea was drilling a hole in a pond to collect water during a reporting trip to Fosheim Peninsula, Nunavut, Canada. He looked up and saw the tent flapping madly in some kind of wind, but the air was calm. It turns out that a white wolf, a member of Fosheim’s famous pack, tore through the tent. Shea pulled out all his belongings, placed them on the grass, grabbed an inflatable pillow, and watched him fly away over the Arctic plains, giddy like a dog with a chew toy.

Shea’s encounter with the pillow-stealing wolf is just one of many shocking images and anecdotes in his new book, Frostline: A Journey Through Intertwined Lives and Landscapes in the Warming Arctic. Shea spent 20 years as a reporter for National Geographic, a role that took him many times to the Earth’s circle located at approximately 66.5 degrees of latitude and above. In this slim, six-chapter book, Shea recalls her most memorable encounters with the people, animals, and nuna (an indigenous word for land with many meanings) of the Arctic, capturing the horror and beauty of a place that many dismiss as “big, cold, white, and far.” What emerges is an elegiac portrait of a region in flux, a land where ice is melting, animals are meandering, elders are dying, and whose fate is inextricably tied to ours.

Book review — “Frostlines: A journey through the intertwined lives and landscapes of a warming Arctic” by Neil Shea (Ecco, 240 pages).

When readers imagine a changing Arctic, they likely think of climate change. One can imagine a version of “Frostline” in which readers are bombarded with abstract stakes and research about melting ice, a version in which Shea packs Southern concerns about global warming into a story about northern people and places. The younger Shea may have written that book. When he first began reporting on the region, he writes, he peppered his sources with questions drawn from Southern thinking about warming and melting ice. But during an ice fishing expedition with an Inuit patrol near the famous Northwest Passage, he woke up. “One thing I quickly learned here is that when you’re camping on a frozen lake, no one wants to talk about climate change,” he writes.

Over the years, Shea has learned the philosophy of “see more, ask less.” This philosophy serves this book immeasurably. He creates investment in the reader by letting the stories he collects speak for themselves, immersing us in the sublime beauty and unique culture of this place.

Join Sia as we watch narwhals touch their tusks in Admiralty Bay. We will visit Fosheim. A pack of white wolves, like those who stole Shia’s pillow, live there. They did not learn to be afraid of others in their solitude. (These wolves are just as likely to gather around humans “like students attending a lecture” as they are to drop a musk ox.) We hear about a time when a bear absentmindedly chased a shea across the sea ice, but the memory comes back to us in a dream, bringing to mind “the blue of the ice, the black of the bear’s eyes, the bright red blood of the fur of the seal it had recently eaten.” We go with him to an archaeological excavation site in Greenland. So Danish researchers are looking for answers about the fate of a Norse colony lost in the Middle Ages. Then, you’ll go on patrol with the Rangers, a volunteer unit of the Canadian military that watches over the tundra as the “eyes and ears of the north.”

Shea’s attention to detail and evocative prose draw readers into his experiences. He ate “boiled seal with ketchup” and rode a four-wheeler into “a meadow of dark green sedge, filled like a shrine with the bleached bones of musk oxen.” The fish resembles the “arch of a woman’s foot.” A rock outcrop, “a large hook-beaked gargoyle.”

However, the Arctic is more than just a series of beautiful landscapes. Also, 4 million people live here, and for them “cold is freedom”. In introducing us to humans living in the Arctic, Shea complicates and illuminates a place that many southerners mischaracterize or misunderstand. He exposes “the line of dissonance drawn between the white world, the world of science and politics, and the world of indigenous peoples who relied on alternative ways of seeing, evaluating, and negotiating reality.”

In the American and Canadian Arctic, still under the long shadow of colonialism, many of Shea’s interviewees are less concerned about climate change than the death of their elders and the accompanying loss of traditions and knowledge. Shea originally went on an adventure to observe the melting ice along the Northwest Passage, where she met Jacob, a hunter of animals such as seals and whales. Jacob lives “the old-fashioned way” and teaches his son his native language. A few years later, Jacob died of complications from COVID-19. In Alaska, Shea visited a community concerned about the decline of the local caribou herd, where she witnessed an elder teaching schoolchildren how to slaughter these caribou, unaware that the man would suffer a heart attack and die the next day. Along with Shia, we witness the end of a way of life in real time.

But Shea refuses to establish a simple dichotomy between the beauty of tradition and the corrosiveness of modernity. He also shows the difficulty of living in an area that lacks even basic amenities that outsiders would consider an afterthought. In one passage, Martin, Jacob’s son and a Rangers commander, laments the lack of cell phone service in his town, telling Shea, “It kind of sucks that you can’t call the doctor when your kid gets sick.” Shea reminded him that there was no doctor in town anyway. Through the lens of these voices, a complex Arctic emerges, filled with people who grieve lost traditions while at the same time resenting governments in the South who treat them as a top priority.

Shea originally wanted to circumnavigate the entire Arctic Circle starting in Alaska and ending in eastern Russia, but the war in Ukraine put a halt to those plans. In the final chapter, Shea confronts this situation head-on by taking us to Kirkenes, a Norwegian town on the border with Russia. There he interviews journalists writing about his homeland in exile, visits a bridge built when the Nazis occupied the city during World War II, and meets Norwegian conscripts who spend their days looking through telescopes at Russia. In this essay, Shea paints a very different portrait of the Arctic than the ruins of Greenland or the wolf packs of Canada. This was “the most violent Arctic I have ever seen, full of real and imagined bloodshed,” he wrote. These geopolitical tensions, including President Donald Trump’s increasingly aggressive moves to annex Greenland, cast a shadow over the Arctic, a battleground where great powers compete for control of precious resources as the world warms.

Shea’s writing occasionally veers into overly poetic chronicle or sentimentality, as in a passage in which he posits that the mayor of an Alaskan town is obsessed with preserving Native knowledge as punishment for past crimes. But overall, “Frostlines” is an intricately observed and completely immersive travel and science text, as well as a vivid and persuasive argument for why readers should care about this region.

The Arctic has a unique natural environment, he writes, “where you can see things you can’t see anywhere else.” Even if you didn’t think this place was important before, you will after reading this book. And although Mr. Shea focuses on the value of the Arctic itself rather than its value in relation to Antarctic issues, the fact remains that caring for the Arctic means caring for all of us. Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier writes, “What is happening in the Arctic today is the future for the rest of the world.”