The Economist managed to sink to an incredible low with a new article about the “ChatGPT moment” for manufacturing. The company has displayed an impressive display of ignorance, never once mentioning China in a multi-page article about the future of production, let alone the uproar in Western boardrooms over China’s introduction of dark factories and China’s leadership in robotics and related technologies. Has The Economist been living under a rock?

There is no justification for the grotesque dishonesty of positively ridiculing the reader. Information collectors trying to navigate the hall of mirrors created by propaganda may be aware that The Economist is the proud go-to magazine for the Ukraine war. For example, it regularly depicts Russia’s military and economy as badly managed and on the verge of collapse. But The Economist holds the cards for Britain’s elite. The national leadership is fully committed to Project Ukraine. So I don’t know if it’s because their critical thinking skills are turned off or because they consider their patriotic duty to fall under “Truth is the first casualty of war,” but I can kind of understand why The Economist rebels against the British establishment and doesn’t try to do real journalism on the subject.

But how could we have overlooked the panic among Western manufacturing industries, especially the auto industry, over the proliferation of so-called dark factories? A dark factory is a factory that is so highly automated that it operates with the lights turned off because there are no workers inside. It’s hard to imagine that the author didn’t intend to misinform when he never quotes that phrase even though the setting approaches the concept of a dark factory. From above:

“You know what really moved me? I saw a robot pick up eggs!” exclaimed Roger Smith, chairman of General Motors, in 1985. The American automaker, which was the first company to introduce a robotic arm 20 years ago, was building a “factory of the future” in Saginaw, Michigan. To ensure his company would not lose out to its Japanese rivals, Smith envisioned a “lights out” strategy that would use only machines and no humans. As a result, the shambolic robots were unable to differentiate between car models, and were unable to attach bumpers or paint them properly. The cost has significantly exceeded the budget.

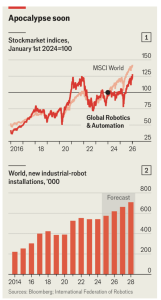

Automation has come a long way since then. But Smith’s vision remains far ahead of reality in most factories. According to industry group International Federation of Robotics (IFR), there will be approximately 4.7 million industrial robots in operation around the world in 2024, or just 177 for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. Annual installations have increased throughout the 2010s, emerging during the pandemic-era automation frenzy, but have since leveled off to 542,000 installed in 2024.

fork. Dear Sports Fans, The Economist, by contrast, takes seriously the position that a development that we dare not name is on the horizon. The message is further reinforced by the chart label “Apocalypse Coming Soon” and the following text:

This is also reflected in the broader market for factory automation equipment, such as sensors, actuators and controllers, which has faced rapid demand over the past few years amid a manufacturing slowdown, particularly in Europe.

But analysts believe 2026 will be a turning point. IFR predicts that annual robot installations will increase to 619,000 this year (see Figure 2). Consultancy Roland Berger predicts that inflation-adjusted sales growth for overall industrial automation equipment will rise from just 1-2% in 2025 to 3-4% in 2026, and then 6-7% for the remainder of the decade.

As the population ages, many manufacturers struggle to find enough skilled operators to staff assembly lines, increasing demand for machinery.

Additionally, advances in industrial software are overcoming many of the challenges that previously hindered efforts to automate production.

It took me about a nanosecond of searching to find a large, supposedly authoritative study by Grandview Research that challenges this characterization, with plenty of anecdotes: Dark Factory Markets (2025-2030). First, let’s investigate Grandview.

The global dark factory market size is estimated to be USD 119.19 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 8.7% from 2025 to 2030. This growth is primarily driven by the increasing adoption of industrial robots and automated guided vehicles (AGVs), which enable continuous manufacturing with minimal human intervention. Additionally, the expansion of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) enables real-time data monitoring and predictive maintenance, significantly increasing operational efficiency.

Integrating AI and machine learning into manufacturing processes further enhances decision-making and self-optimization capabilities in dark factory environments. The demand for faster, more precise production in industries such as automotive, electronics, and pharmaceuticals is also driving the adoption of machine vision systems and additive manufacturing technologies. Furthermore, the global shift towards digital transformation and Industry 4.0 initiatives is accelerating the adoption of fully automated smart factories, driving further growth in the dark factory industry.

The increasing adoption of industrial robots in dark factories enables continuous automated production with minimal human intervention. These robots improve manufacturing accuracy, speed, and consistency, helping companies reduce costs and increase efficiency. Industrial robots continue to reshape the future of the dark factory industry as demand for scalable and error-free production increases.

Additionally, ongoing digital transformation is playing a key role in driving industry growth, with companies across industries increasingly integrating advanced technologies such as IoT, AI, and cloud computing into their manufacturing ecosystems. This integration enables real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and autonomous decision-making, enabling manufacturers to increase efficiency, reduce downtime, and improve product consistency, thereby driving industry growth.

It also helps identify key hires.

And this sort of thing pales in comparison to media articles and YouTube videos, indicating that the idea that China’s black factories are set up to eat Western manufacturers’ lunch is gaining enough traction in the broader media, not just the business press. Some of the many examples:

March 15, 2025 The Rise of the “Dark Factory”: How AI-Driven Manufacturing Automation is Transforming Global Manufacturing from Algorithmic to Advanced: Mahendra Rathod’s Random Thoughts

April 16, 2025 The Rise of the Dark Factory: China’s Fully Autonomous Manufacturing Revolution Asia Lifestyle Magazine

May 1, 2025 XIAOMI’s innovative new dark factory will operate 247 days without breaks, lights and personnel

July 22, 2025 What are China’s “black factories”? Will the American auto industry follow suit? What you need to know about USA Today

September 4, 2025 Inside China’s “black factory” where robots manufacture EVs 24/7, threatening the world’s automakers Electric Vehicle Headquarters

September 16, 2025 Will the U.S. ever achieve a fully automated “black factory”? Manufacturing Dive

October 12, 2025 Western executives who visited China return home terrified Telegraph

The Telegraph article generated a number of follow-up reports with additional data and sightings, including:

October 14, 2025 Western executives upset by futurist visit to China

October 16, 2025 “Dark Factory: The Rise of Robot Manufacturing in China” LinkedIn

This humble blog is much more advanced than The Economist. Our stories focused on dark factories include:

April 30, 2025 China overtakes the US in technological innovation

November 23, 2025 Mission Impossible: Why America Can’t Reverse Manufacturing Decline

I introduced this YouTube:

A sample from the many YouTube videos profiling dark factories:

The Rise of the Black Factory | A Bold Leap in Automation in Manufacturing (7 months ago)

China’s underground factories: Automated so no lighting required | WSJ (5 months ago)

Inside China’s ‘dark factory’ where robots run production lines • France 24 English (1 month ago)

The Economist article focuses on Siemens. Perhaps I’ve overlooked something, but I’ve never seen a German stalwart characterized as a leader in factory automation. However, The Economist portrays Seamans as cutting edge:

Hints of the future can already be glimpsed at automation equipment maker Siemens’ Bavarian factories in Amberg and Erlangen… Robotic arms, many of them manufactured by Universal Robots, whose parent company is American company Teradyne, do more than pick up eggs. Move around quickly, welding, cutting, assembling, and inspecting inside a glass enclosure. Workers monitor and control production from a computer connected to the machine.

The Erlangen factory (pictured), which produces electronic components, is similarly futuristic. Autonomous trolleys fitted with screens move around the worksite, transporting goods between stations where humans and robots work in parallel. Some people line up neatly and charge.

This story includes a photo of a very brightly lit room and a photo of a room with a human operator.

Now, some may try to lamely defend The Economist by pointing out that even with electric cars, which have low parts intensity, there are still no underground car factories in China. Humans are still used in some operations. They do the same for phones, and I’m guessing the same goes for medicines. However, numerous stories have revealed that many producers manufacture the overwhelming majority of the parts for these cars on a black factory basis. A January 2026 article in Automotive News Europe predicts that by 2030, cars will be manufactured in completely dark factories.

But seriously, what excuse does The Economist have for this embarrassment? Did Siemens plan the story and an Oxbridge freshman who could read German (in both senses of the word) write it? Did equity analysts sell the opposite idea that Europe could do well with introducing AI into factories and somehow ignore the China elephant in the room? Or was this work written by AI?

Either way, it definitely misleads the reader. If you subscribe to The Economist, you will need to cancel your subscription or request a refund for this issue.