Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What is the biggest risk plaguing the world? Back in 2010, it was fiscal and monetary threats, at least according to the annual survey of participants at the World Economic Forum in Davos. And in 2020, environmental issues topped the league.

Judging by the latest WEF poll, concerns about war now predominate, both on the athletic and economic fronts. Financial issues fell to 17th place. This is shocking. But as Davos gathers next week, investors need to remember an important point: WEF consensus is often wrong. Some hedge fund types even joke that the smartest trade is to do the opposite of what the Davos rhetoric suggests.

So, in the words of the WEF, could 2026 be the year when fiscal risk finally explodes in the “economic calculations”? At a time when markets seem to be calming down, should we care that global debt is over 235% of global GDP and rising?

This is an interesting question to ponder in the United States, where the debt-to-GDP ratio is over 100 percent and President Donald Trump is forcing the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates to reduce debt servicing costs. The same is true for the UK, given slowing economic growth and rising debt.

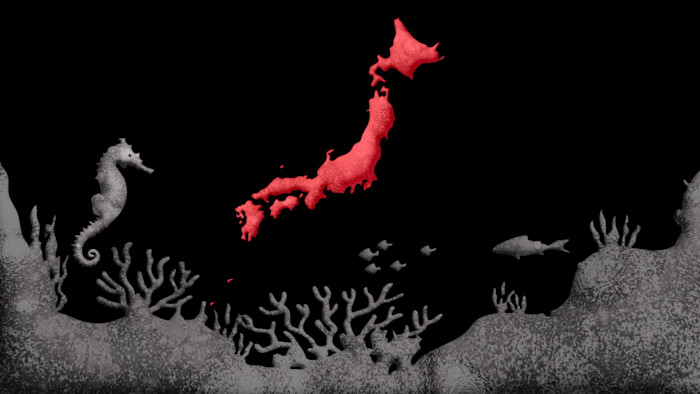

But another place worth discussing more is Japan, whose (infamous) net debt and gross debt-to-GDP ratios are 130% and 240%, respectively. Japan is currently the darling of stock investors around the world. That’s because it appears relatively stable compared to the United States, and Japanese companies are important to global supply chains in areas ranging from robotics to shipping.

Even better, its new(ish) leader, Sanae Takaichi, promises economic reform and enjoys an impressive 76 percent approval rating, thanks in part to her refreshing style. Indeed, Japan’s stock market hit a record high this week amid news that Takaichi will declare a snap election to consolidate his power. The move could bring about a $135 billion stimulus package and further reforms.

So far it’s been very exciting. However, this week, the yen also fell to nearly 160 yen to the dollar. It’s as amazing as Takaichi’s drums. “The yen/dollar purchasing power parity is in the 90s, according to both the IMF and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development,” said Peter Tasker, Japan analyst at Arcus.

And while this weakness was once blamed on Japan’s zero interest rate policy, this week the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield hit 2.16%, significantly higher than in recent years.

why? Robin Brooks, former chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, believes this signals an impending crisis. “The yen is falling because the market wants interest rates to rise, but interest rates remain artificially low and are not sufficiently compensating for what investors see as increased default risk,” he argues. And the Bank of Japan wants to end quantitative easing, which would raise service costs and “risk pushing Japan into a fiscal crisis,” Brooks said. “Japan is trapped”

Others like Tasker disagree with this. “Some people seem to be enjoying the apocalyptic narrative about Japan’s finances,” he says, arguing that rising interest rates are “just another piece of evidence that Japan is getting back to normal.” More specifically, as Overshoot’s Matthew Klein points out, Japan is finally showing growth and rising prices after years of stagnation.

This has already reduced the deficit. And one issue that could reduce the threat of a debt burden is that more than 90 percent of the national debt is held domestically. This means that even if haircuts occur in the future, the market may find it easier to swallow them than in places like the US or Europe, as Japan still has a strong culture of shared sacrifice and patriotic duty.

However, it may not be possible to protect Japan forever. As the Bank of Japan points out in its latest Financial Stability Report, “foreign investors, including hedge funds, have significantly increased trading volumes in the government bond market.” In fact, somewhat surprisingly, they account for two-thirds of all cash transactions, likely because hedges engage in so-called basis trading with government bonds, similar to U.S. Treasuries.

In 2020, the U.S. Treasury market crashed when basis trading in U.S. Treasuries was suddenly unwound. And the same thing could happen again in Japan, especially given the rise of the yen carry trade. This means that once a financial panic breaks out, it can quickly worsen.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not predicting that Mr. Takaichi (whom I respect) will fail. Furthermore, a crisis in U.S. bonds and government debt will not occur immediately. But the important point is this. What is happening in Japan reflects a contradiction. In other words, debt continues to grow relentlessly, but most investors seem intent on giving the government a profit. Never mind that I have no idea how this will be resolved. This complacency is likely to continue into 2026. But silence alone cannot eliminate the risk of a so-called Wile E. Coyote moment, when investors suddenly look down and panic.

Please remember. Back in 2018, as I pointed out at the time, Davos had no interest in talking about the risks of a pandemic. The ensuing outbreak of COVID-19 shocked me and made me wonder why I was ignoring what was hidden in plain sight. Let’s hope something like this never happens again in the financial world. Silence is just as important as noise.

gillian.tett@ft.com