Eve is here. This VoxEU article about the systemic risks posed by AI comes as even popular media outlets express concern about exactly this kind of exposure. But a new article in Time magazine, oddly enough, portrays the real risk as panic, as opposed to a major failure that cannot or may not be easily repaired. Contrast Time’s upbeat view with a more comprehensive and consequently more sober assessment by VoxEU’s experts. The world has traditionally been unprepared for AI emergencies:

You wake up in the morning to find the internet flickering, card payments failing, an ambulance heading to the wrong address, and emergency broadcasts you’re no longer sure you can trust. Whether caused by malfunctioning models, criminal exploitation, or widespread cyber shocks, AI crises can quickly cross borders.

Often, the first signs of an AI emergency will look like a general outage or security failure. It is only later that it becomes clear that AI systems played a significant role, if at all.

Some governments and businesses are beginning to build guardrails to manage the risks of such emergencies. The European Union AI Act, the National Institute of Standards and Technology Risk Framework, the G7 Hiroshima Process, and international technical standards all aim to prevent harm. Cybersecurity agencies and infrastructure operators are also developing operating procedures for hacking attempts, outages, and routine system failures. What’s missing isn’t a technical strategy for patching servers or restoring networks. This is a plan to prevent social panic and a breakdown in trust, diplomacy, and basic communication if AI were to sit at the center of a rapidly evolving crisis.

Preventing AI emergencies is only half the job. The missing half of AI governance is preparedness and response. Who decides whether an AI incident has become an international emergency? Who will speak up to the public when false messages flood their feeds? Who will keep the intergovernmental channels open if the normal lines are compromised?…

We don’t need new, complex institutions to oversee AI. All that is needed is for the government to plan ahead.

In contrast, this article finds that AI risks are considered multifaceted, as they often have the potential to amplify existing dangers, and much needs to be done for prevention.

By Stephen Cecchetti, Rosen Family Chair in International Finance, Brandeis University School of International Business, Vice-Chair of the European Systemic Risk Committee, Advisory Scientific Committee, and Robin Ramsdane, Crown Prince of Bahrain, Professor of International Finance, Kogod School of Business, American University. Tuomas Peltonen, Professor of Applied Econometrics, Faculty of Economics, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Deputy Secretary General of the European Systemic Risk Committee, and Antonio Sánchez Serrano, Senior Lead Financial Stability Expert, European Systemic Risk Committee. Originally published on VoxEU

While artificial intelligence brings significant benefits to society, including accelerating scientific progress, improving economic growth, improving decision-making and risk management, and enhancing health care, it also raises significant concerns about risks to the financial system and society. In this column, we discuss how AI can interact with the main sources of systemic risk. The authors then propose a combination of competition and consumer protection policies, complemented by prudential regulation and supervisory adjustments to address these vulnerabilities.

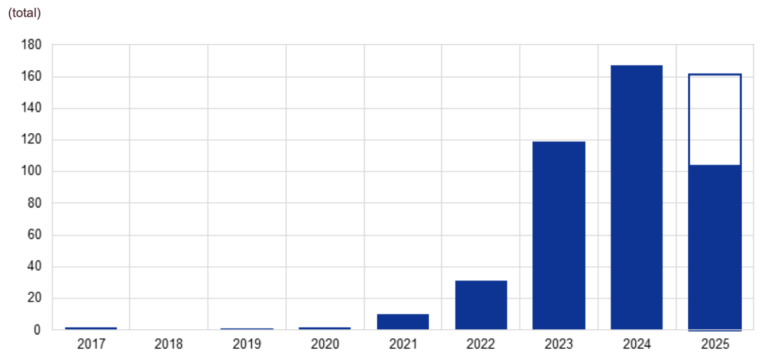

In recent months, we’ve seen companies invest heavily in developing large-scale models (models that require more than 1023 floating-point operations to train), such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft’s Copilot, and Google’s Gemini. Although OpenAI doesn’t release exact numbers, recent reports indicate that ChatGPT has around 800 million weekly active users. Figure 1 shows the rapid increase in the release of large-scale AI systems since 2020. The fact that people find these tools intuitive to use is no doubt one of the reasons for their rapid adoption. Companies are working to integrate AI tools into their processes, in part because these tools are seamlessly integrated into existing everyday platforms.

Figure 1 Number of large-scale AI systems released per year

Note: Data through August 24, 2025. The white box in the 2025 bar is the result of extrapolating the data to that date for the full year.

Source: World of Data.

There is a growing literature examining the impact of the rapid development and widespread adoption of AI on financial stability (see, among others, Financial Stability Board 2024, Aldasoro et al. 2024, Daníelsson and Uthemann 2024, Videgaray et al. 2024, Daníelsson 2025, Foucault et al. 2025). A recent report of the Scientific Advisory Board of the European Systemic Risk Committee (Cecchetti et al. 2025) discusses how the characteristics of AI interact with different sources of systemic risk. We identify relevant market failures and externalities and consider their implications for financial regulatory policy.

Development of AI in our society

Artificial intelligence, including both advanced machine learning models and recently developed large-scale language models, can quickly solve large-scale problems and change the way resources are allocated. Common applications of AI include knowledge-intensive tasks such as (i) supporting decision-making, (ii) simulating large networks, (iii) summarizing large amounts of information, (iv) solving complex optimization problems, and (v) drafting text. There are many channels through which AI can improve productivity. These include automation (or the deepening of existing automation), enabling humans to complete tasks more quickly and efficiently, and enabling them to complete new tasks, some of which have not yet been imagined. However, current estimates of the impact of AI on overall productivity tend to be very low. In a detailed study of the US economy, Acemoglu (2024) estimates that the impact on total factor productivity (TFP) will range from 0.05% to 0.06% per year over the next decade. This is a very modest improvement, as TFP has increased by an average of about 0.9% per year in the United States over the past quarter century.

Estimates suggest mixed effects across the labor market. For example, Gmyrek et al. (2023) analyzed 436 occupations and identified four groups. Occupations that are least likely to be affected by AI (mainly consisting of manual and unskilled workers), occupations where AI will augment and complement their tasks (such as photographers, elementary school teachers, and pharmacists), occupations that are difficult to predict (especially financial advisors, financial analysts, and journalists), and occupations that are most likely to be replaced by AI (such as accounting clerks, word processing operators, and bank tellers). Using detailed data, the authors conclude that 24% of office jobs have high exposure to AI, and a further 58% have moderate exposure. For other occupations, we conclude that roughly a quarter have moderate exposure.

The roots of AI and systemic risk

Our report highlights that AI’s ability to process vast amounts of unstructured data and interact naturally with users allows it to complement and replace human tasks. However, using these tools comes with risks. These include difficulties in detecting AI errors, decisions based on biased results due to the nature of training data, overdependence resulting from too much trust, and challenges in monitoring systems that are difficult to monitor.

As with all uses of technology, the issue is not AI itself, but how both businesses and individuals choose to develop and use AI. In the financial sector, the use of AI by investors and intermediaries can create externalities and spillover effects.

With this in mind, we consider how AI will amplify or modify existing systemic risks in finance, as well as create new ones. We consider five categories of systemic financial risk: liquidity mismatch, common exposure, interconnectedness, lack of substitutability, and leverage. As shown in Table 1, features of AI that can exacerbate these risks include:

Surveillance challenges where the complexity of AI systems makes effective monitoring difficult for both users and authorities. Concentration and entry barriers create a small number of AI providers, single points of failure and widespread interconnectivity. Model homogeneity. Widespread use of similar AI models can lead to correlated exposures and amplified market reactions. Good initial performance makes people overly trusting AI, increasing risk-taking and hindering oversight. Increased transaction speed, responsiveness, and automation can amplify procyclicality and make self-reinforcing counter-effects difficult to stop. Opacity and concealment, where the complexity of AI reduces transparency and facilitates intentional concealment of information. Malicious uses where AI can enhance the ability of malicious actors to commit fraud, cyberattacks, and market manipulation. Illusions and misinformation where AI can generate false or misleading information, leading to widespread misinformed decision-making and subsequent market instability. The historical constraints of AI’s reliance on past data means it may struggle with unexpected “tail events” and lead to excessive risk-taking. If providers and financial institutions face AI-related legal setbacks, ambiguities regarding legal liability for AI actions (such as the right to use data for training or liability for advice provided) could pose systemic risks in an untested legal position. Complexity can obfuscate the system, making it difficult to understand the AI’s decision-making process and triggering execution when users discover flaws or unexpected behavior.

Table 1 How current and potential capabilities of AI can amplify or create systemic risk

Note: Existing AI feature titles are red if they contribute to four or more sources of systemic risk, and orange if they contribute to three causes of systemic risk. Potential AI features are colored orange to indicate that they are not certain whether they will occur in the future. The column displays in red if the source of systemic risk is related to 10 or more features of AI, and in orange if it is related to 6 or more but less than 10 features of AI.

Source: Cecchetti et al. (2025).

Capabilities we have yet to see, such as the creation of self-aware AI or full human dependence on AI, could further amplify these risks and create further challenges arising from loss of human control and extreme social dependence. For now, these remain hypotheses.

Policy response

In response to these systemic risks and associated market failures (fixed costs and network effects, information asymmetry, bounded rationality), we believe it is important to review competition policy, consumer protection policy, and macroprudential policy. Regarding the latter, key policy proposals include:

Regulatory adjustments, such as readjusting capital and liquidity requirements, tightening circuit breakers, amending regulations to address insider trading and other types of market abuse, and adjusting central bank liquidity facilities. Transparency requirements, including adding labels to financial products, to increase transparency around the use of AI. “Skin in the game” and “level of sophistication” requirements for AI providers and users to take appropriate risks. The enhanced supervision aims to ensure that supervisors have adequate IT and staff resources, improve analytical capabilities, strengthen oversight and enforcement, and foster cross-border cooperation.

In either case, it is important that authorities undertake the necessary analysis to gain a clearer picture of the impact of AI, its impact channels, and the scope of its use in the financial sector.

The risks are especially high in the current geopolitical environment. If authorities cannot keep up with the use of AI in finance, they will be unable to monitor new sources of systemic risk. As a result, financial stress will occur more frequently and costly public sector intervention will be required. Finally, it must be emphasized that the global nature of AI makes it important for governments to cooperate in developing international standards to avoid actions in one jurisdiction creating vulnerabilities in other jurisdictions.

See original post for reference