Eve is here. This Wolf Richter provides some important background on the dollar situation. Recall that 1994 was just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and thus a time when American hegemony, at least militarily, was at its peak. And regardless of the Trump administration’s considerable self-inflicted wounds, the dollar’s status as a reserve currency should be expected to decline over time as the US share of global GDP declines.

Written by Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. First appearance: Wolf Street

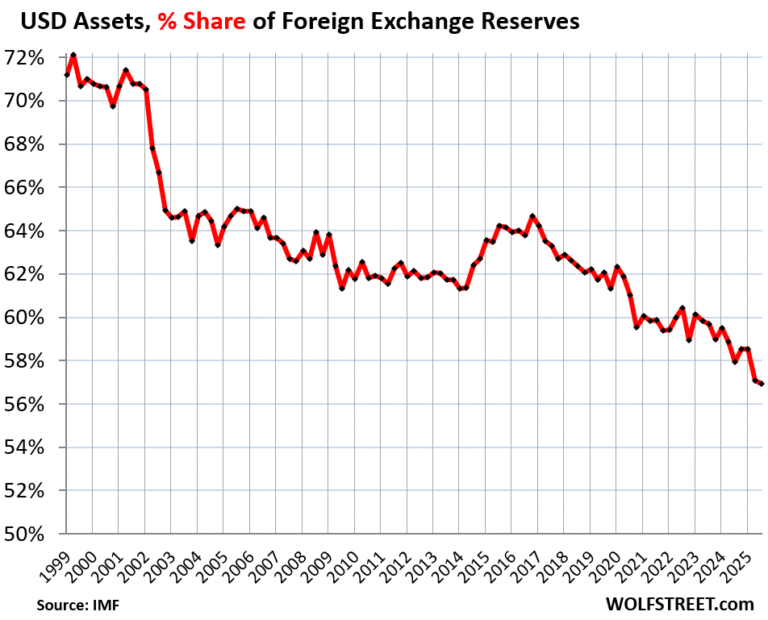

The share of US dollar-denominated assets held by other central banks fell to 56.9% of total reserves in the third quarter, the lowest level since 1994, from 57.1% in the second quarter and 58.5% in the first quarter, according to new IMF data on the monetary composition of official foreign reserves.

U.S. dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves include U.S. Treasury securities, U.S. mortgage-backed securities (MBS), U.S. government agency securities, U.S. corporate bonds, and other U.S. dollar-denominated assets held by central banks other than the Federal Reserve.

Central banks’ domestic currency assets, such as the Federal Reserve’s Treasury bills and the ECB’s euro-denominated securities, are excluded.

Foreign central banks did not sell dollar-denominated assets such as Treasury bills. they didn’t. They increased their holdings a little bit. However, while they added more assets denominated in other currencies, especially the combined share of the smaller currency groups, the share of US dollar-denominated assets continued to decline, as central banks’ holdings of US dollar-denominated assets have not changed much in a decade.

Even if the dollar’s share declines toward the 50% line, it will still be by far the largest reserve currency because all other currencies combined weigh as much as the dollar. But it has consequences.

Why is it important for the United States to have a top reserve currency?

When foreign central banks buy U.S. dollar-denominated assets, such as Treasury bills, prices rise and yields on those assets fall. Being the dominant reserve currency has the effect of allowing the United States to borrow more cheaply to finance its huge twin deficits, the trade deficit and the budget deficit, which have allowed the US to maintain these huge twin deficits for decades. If this decline as a reserve currency continues, demand for U.S. dollar-denominated government bonds will decline, making it more difficult to maintain trade and fiscal deficits.

The dollar’s share was already below 50% in 1990 and 1991, after a long period of decline from its 1977 peak (85.5% share). This precipitous decline was accompanied by a deep crisis in the United States, with soaring inflation and interest rates, and four recessions in between, including a nasty double-dip recession. Central banks have lost confidence in the Fed’s willingness and ability to do what is necessary to control this inflation, which has hit the United States in three waves of unprecedented magnitude.

The dotted line in the graph below indicates 50% share. The dollar’s share bottomed out at 46% in 1991, but by then the Fed had reined in inflation and soon central banks began building up dollar assets.

Then the euro came along and was the next setback for the dollar, but not as much as European politicians had promised when pushing for the euro. They were talking about parity with the dollar. That debate ended with the euro debt crisis that began in 2009.

Then, over the past decade, dozens of smaller “non-traditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them, have emerged.

This graph shows the dollar share at the end of each year. However, 2025 shows the third quarter share.

However, they did not actually sell US dollar-denominated securities.

Foreign central banks increased their dollar-denominated asset holdings to just $7.4 trillion in the third quarter, the third consecutive increase.

Since mid-2014, US dollar asset holdings have been essentially flat, although there have been some sharp ups and downs.

In other words, the decline in the share of US dollar assets over the years has been due to the increase in foreign exchange reserves denominated in other currencies, especially many smaller currencies, as central banks have diversified their ever-growing mountain of foreign currency assets.

The chart below shows foreign central banks’ holdings in US dollar-denominated assets (such as US Treasury securities, US MBS, US government agency securities, and US corporate bonds) in trillions of dollars.

Top foreign exchange reserves by currency

Central banks’ holdings of foreign exchange reserves rose to $13 trillion in the third quarter in all currencies (expressed in US dollars).

Top holdings (in USD):

USD assets: $7.41 trillion Euro assets (EUR): $2.65 trillion Yen assets (YEN): $0.76 trillion British pound assets (GBP): $0.58 trillion Canadian dollar assets (CAD): $0.35 trillion Australian dollar assets (AUD): $0.27 trillion Chinese Yuan (RMB) assets: $0.25 trillion

The share of the second-largest euro has hovered around 20% since 2015. Before the euro debt crisis, it was on the rise and was already close to 25%.

The remaining reserve currency is the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart (more on that later). Combined, the euro’s share has remained roughly stable since 2015, although it has expanded its share over the years at the expense of the dollar.

Rise of “non-traditional” key currencies

The graph below is a magnifying glass magnifying glass of the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the graph above.

The spiking red line shows the jump in total assets denominated in dozens of small “non-traditional reserve currencies” as the IMF calls them. The total share reached 5.6%, slightly lower than yen-denominated assets (5.8%).

However, the share of the renminbi (yellow) has been declining since Q1 2022, returning to 2019 levels amid ongoing capital controls, convertibility issues, and many other issues.

In other words, both the US dollar and the renminbi have ceded market share to “non-traditional reserve currencies” as other central banks sought to diversify away from assets denominated in the US dollar and renminbi.

A slightly less ugly situation, in case you missed my update on the U.S. government’s interest payments on tax revenue, average debt interest rates, and the debt-to-GDP ratio for Q3 2025.