Eve is here. A high-level overview of what’s happened in shadow banking since the financial crisis. As he explains below, despite regulatory pretense, it’s bigger and perhaps worse than before. And unlike in the run-up to the crisis, the Chinese are similarly trapped (for more, see “On a relative scale, there is a strong case that China’s financialization is worse than the US” and “China’s local government financing vehicles (LGFVs): Ponzi finance on steroids”).

Satyajit Das is a former banker and author of numerous technical works and several popular titles on derivatives. “Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives” (2006 and 2010), “Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk” (2011), and “A Banquet of Consequence – Reloaded” (2016 and 2021). His latest book is about ecotourism – Wild Quests: Journeys into Ecotourism and the Future for Animals (2024). This is an expanded version of an article that first appeared in the New Indian Express print edition on November 28, 2025.

In the 2008 crash, unregulated financial institutions (structured investment vehicles, asset-backed commercial paper issuers, securitization structures, money markets, and hedge funds) contributed to financial instability. In the aftermath, regulators pledged to regulate “shadow banks” (preferring the more pejorative “market-based finance” or “non-bank financial institutions”). But that didn’t happen.

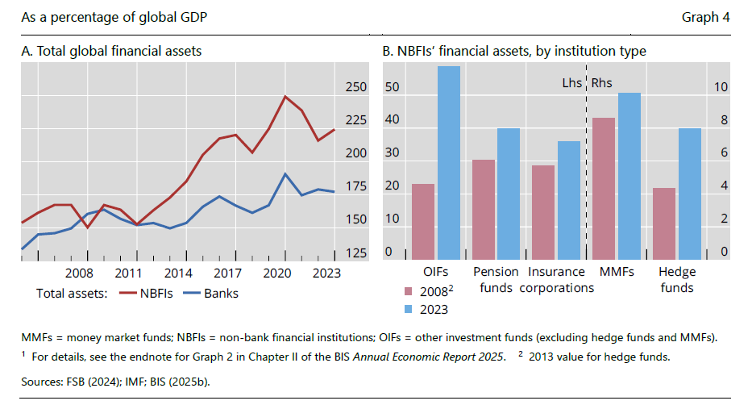

In fact, the share of global financial assets held by shadow banks has increased since 2008 (see chart below). The total value of assets held by insurance companies, private credit providers, hedge funds, and other non-bank financial groups is approximately $257 trillion, an increase of 9.4% in 2024. In contrast, bank assets grew by 4.7% to just over $191 trillion in 2024.

As of 2024, total financial assets in shadow banks will represent 225% of global GDP, up from 150% in 2008. By comparison, bank assets, which are growing more slowly, are at 175%. Since 2008, hedge funds have doubled in size, reaching 8% of GDP.

Some structures have declined or disappeared, while others have flourished or new structures have appeared. Currently, the shadow banking complex is dominated by asset managers such as insurance companies, pension funds, non-bank financial companies, and collective investment vehicles (funds, investment companies or partnerships, hedge funds) that invest their customers’ funds in public equities, private equities, bonds, or hybrid securities. Other examples include securitization vehicles, which repackage existing debt into new securities with different characteristics, and various quantitative or multi-strategy trading firms. Other types of specialized fintech companies, microloan organizations, and trade lenders include debt lenders, asset-based lenders (offering leases, secured loans, or debt financing), payday lenders, pawnshops, and loan sharks. This phenomenon is global. For example, China has a particularly wide range of shadow banks, offering wealth management products, trust loans, entrusted loans, and undiscounted bank acceptances.

We have something in common. All these absurd operations mediate the flow of capital between investors (retailers, wealthy individuals, family offices, institutions, sovereign wealth vehicles) and companies. They trade in financial markets using various strategies to earn profits from buying and selling financial instruments. Most importantly, banks theoretically do not accept deposits from the public and are not part of the payment system, so regulations are limited compared to those applicable to banks.

Current regulatory concerns about this sector are disingenuous because the actions of policymakers underlie its growing role. Stricter banking regulations, such as the Basel 3 agreement agreed since 2008, limit or increase certain types of financing, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises, real estate, and projects. This has allowed shadow banks to expand to meet credit demands. The long period of low interest rates from 2008 to 2021 also encouraged investors to seek better returns in an ever-changing investment world. In Asia, banks’ bad loans have made it difficult to meet loan demand. Differences in capital, leverage, and liquidity requirements have led to regulatory arbitrage.

The effects of the policy are mixed. Part of the reason for the rise in securitization is that the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank hold more than 16,53, or about 27, or 30 percent of outstanding government debt, making it less available. Highly rated securitized bonds meet the demand for safe assets and collateral for secured loans.

Interestingly, regulated banks have benefited from the growth of shadow banks. They refocused their business model from a “storage business” to a “transportation” business. By underwriting loan assets and distributing them to funds and insurance companies, banks can now more effectively “squeeze capital” and increase returns on shareholder funds. For central banks, this increases the speed at which money moves within the economy.

Many banks are now circumventing restrictions on taking proprietary positions by setting up once-star in-house traders in external hedge funds. The main benefit is the income earned from trading off-balance sheet financial products and providing services such as clearing and custody. Banks also have significant influence on these instruments in the form of loans secured by assets or non-financial derivative structures. The large profits from prime broking (these terms of service) are proof of that opportunity.

Banks may receive income from investments in these funds. Their wealth management and private banking departments can invest in these external entities and offer products built by those external entities.

Shadow banks are significantly changing the financial system and introducing risks that are not well understood. These make it difficult to measure increases in debt levels, which can exacerbate price bubbles across multiple asset classes.

The higher returns offered to investors suggest that shadow banks take on greater risks, unless some secret chemical process allows them to circumvent normal financial logic. As bank lending is concentrated among safer borrowers, nonbanks may extend credit to lower-rated debtors and riskier assets. Shadow banks often utilize higher levels of leverage than regulated institutions to increase yields. Leverage tiering also increases risk across the financial system. It also relies heavily on a flawed collateral system to support credit risk. All of this poses potential problems during an economic or financial downturn.

Difficulties are compounded by the fact that many shadow banks are funds that pass through investor money, meaning they lack the capital to absorb permanent losses. There are concerns regarding liquidity and redemption risk. To maintain profitability, most shadow banks must remain fully invested with a limited capital buffer. Given the wide misalignment of asset and liability maturities and the holding of illiquid assets that offer higher yields, unexpected large investor withdrawals can create sudden cash pressure. For some institutions, such as pension funds and insurance companies, reduced revenues, losses or inability to access cash may affect their ability to service their contractual obligations.

There are important connections between regulated organizations and their shadow counterparts. U.S. banks alone owe $300 billion in loans to private lenders, making up a significant portion of all loans. In addition to loans to private credit providers, there was an additional $285 billion in loans to private equity funds as of June, and $340 billion in undrawn commitments available to these borrowers. Banks also provide large sums of money, currently about $3 trillion, in prime brokerage loans to hedge funds and other leveraged investors. The total exposure of US and European banks to nonbank financial institutions is estimated at $4.5 trillion.

The main factor is the treatment of differential capital. Regular bank loans, excluding mortgages, are typically 100% risk-weighted. In contrast, lending to shadow banks has a lower risk weight of around 20%, which can substantially reduce the capital that needs to be held against exposure. This reflects collateral or financial engineering, where structures such as securitization and credit risk transfer mechanisms are used to allow banks to obtain senior exposure to a pool of assets, allowing other banks to absorb some of the initial losses. This makes lending to shadow banks less capital intensive and more profitable.

Instead of addressing the fundamental problem, policymakers are attempting to shift risk from regulated depository institutions to nonbanks. They chose to believe that they could isolate problems in the shadow banking sector and prevent it from infecting banks, thus avoiding unpopular intervention and bailouts using public funds. The collapses of Greensill Capital and Archegos, which led to the collapse of Credit Suisse, point to a different reality. The risks are further exacerbated by the opacity and complexity of these entities.

The most stringent regulatory response would be to strictly isolate shadow banks. Regulated companies and their transactions will be covered by 100 per cent cash collateral to minimize exposure. Strict enforcement of the ban on bailouts would minimize moral hazard.

A less burdensome approach is oversight and regulation based on function rather than legal form. This allows for greater nuance and flexibility in addressing differences between entities, their activities, and risk profiles. Depending on the type of activity, minimum capital requirements, maximum leverage, and maintenance of sufficient liquidity to meet potential redemptions are mandatory. Reliance on short-term funding will be constrained. Vetted sponsors must meet predetermined criteria for capital, skills, and governance. Banks’ exposure to loans and other transactions to non-bank institutions will be regulated. Appropriate protections and disclosures will be made.

However, meaningful regulation is unlikely to be introduced, not only because of the strength of financial sector lobbying, but also because of fears that credit availability would be significantly reduced. A growing factor is that shadow banks are significant holders of government debt (see graph below). Since 2021, developed countries’ debt holdings in this sector have increased to over 50% of GDP. By comparison, banks and central banks hold less than 20%. Hedge funds’ sovereign debt exposure more than doubled to about $7 trillion, with some of the funding coming from repo borrowings, which nearly tripled to more than $3 trillion.

This means there is a clear lack of appetite for measures to regulate shadow banks, as this would require addressing debt levels and changing borrowing-driven economic models.

In the next financial crisis, shadow banks will once again exaggerate asset price declines, increase volatility and cause financial instability.

© Satyajit Das 2025 All Rights Reserved