The Philippines is often described as a country beset by a spate of internal conflicts, including colonial rebellions, communist insurgencies, separatist wars, and Islamist terrorism. This framing obscures deeper continuities. What the Philippines experienced instead was a sustained and destructive state of war, created and sustained by its incorporation into U.S. grand strategy beginning in 1898. From that point on, internal conflicts were no longer treated primarily as political failures to be resolved, but as security situations to be managed as long as the country’s strategic alignment and usefulness were preserved. The result was more than a century of instability, which was neither accidental nor temporary, but structurally conditioned by the Philippines’ role as a strategic asset of the United States.

Before the pivot: Spanish rule and incomplete integration

Spain’s colonization of the Philippines, which began in the 16th century, never produced a fully integrated polity. Governance was uneven and exploitative, relying on local intermediaries rather than durable institutions. Most of the archipelago, especially the Muslim-majority island of Mindanao, was never fully conquered or incorporated. Resistance was chronic, authority fragmented, and political cohesion tenuous.

This history is important not because Spanish rule was uniquely brutal and incompetent, but because it left behind a fragmented political landscape. Spain created instability but never codified it. Although rebellions existed, they were temporary and localized, and had not yet been institutionalized as a permanent security state. This would change decisively at the end of the 19th century.

1898: From colonies to chess pieces

In 1898, after the Spanish-American War, the Philippines became a territory of the United States. More importantly, it became a strategic base for the United States. From Washington’s perspective, the archipelago was no longer just a former colony with governance problems. It was an outpost in the Pacific, a gateway to Asia, and a symbol of America’s rising power.

This strategic restructuring changed the logic of governance. The Philippine-American War that followed was not just a war of conquest. It was an early exercise in modern counterinsurgency. Pacificization, intelligence gathering, population control, and the professionalization of security forces became the means of central governance. Domestic violence was reframed not as a political failure requiring consolidation and reform, but as a technical problem requiring management.

By 1902, organized resistance to U.S. rule had been decisively crushed. The operation, which combined intelligence targeting, population control, and punitive force, demonstrated the feasibility of defeating an insurgency without addressing its underlying political causes. Although costly and brutal, it restored order sufficient for strategic purposes. In doing so, it established a precedent that counterinsurgency could be treated as a technical and organizational rather than a political problem. This lesson would later be reflected in American military doctrine, with unfortunate consequences.

The Philippines thus entered the American security establishment not as a sovereignty project to be completed, but as a position to be maintained. This strategic restructuring did not happen in a vacuum. In the early 20th century, American ideas about power were heavily influenced by the naval theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan, who argued that a nation’s greatness depended on command of its seas, outposts, and major sea routes. In this framework, the Philippines’ value lies not in its political cohesion or social development, but in its position straddling the Western Pacific.

The archipelago was conceived as a platform to be held, rather than a nation to be integrated. Its strategic logic did not require internal stability. Only the chaos remained manageable. Therefore, from the beginning, the Philippines participated as a positional asset in US grand strategy, subordinating internal conflicts to external orders.

japanese strategy

Japan’s conquest of the Philippines during World War II emphasized the strategic logic that was already shaping American policy. Japan occupied the archipelago not because of its domestic politics or social structure, but because of its location across major sea routes and its value as a base for front-line operations. The rapid collapse of America’s defenses in 1941 revealed a fundamental reality. In a conflict between great powers, the Philippines’ internal stability was strategically irrelevant. The key was denial, access, and control. The war thus confirmed the role of the Philippines, not as a sovereign state to be defended for its own ends, but as a positional asset whose fate was determined by external strategic competition.

The lesson for the United States from this experience was that political unity in the Philippines should not be prioritized, but that strategic alignment and access must be ensured under all conditions. When the United States returned from the war, it adopted a security posture designed to prevent strategic losses rather than complete political integration.

Permanent counterinsurgency as the norm

After the war, counterinsurgency became established as a governing norm. The Philippine security apparatus was formed around containment, not resolution. Stability has come to mean suppressing threats below an acceptable threshold, rather than eliminating the structural factors that create them.

This approach has proven durable. Rebellions can be weakened, fragmented, or temporarily suppressed without being resolved. Security forces became tactically adept. There has also been a steady flow of aid from outside. The state continued to exist, elections were held, and formal sovereignty was maintained.

What never emerged was a political settlement that could integrate surrounding regions, address land inequalities, and dissolve the incentive structures that perpetuate rebellion. Low-level conflict has become sustainable. In this sense, disorder is not a failure of the system. It was an equilibrium created by the system.

repeated rebellions

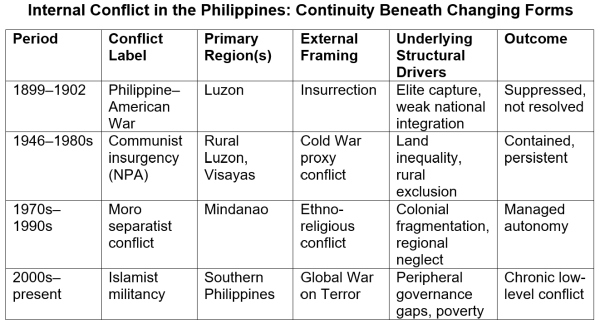

The persistence of civil war in the Philippines was often obscured by changing ideological labels. Communist insurgency, Moro separatism, and Islamic extremism have each been treated as separate problems requiring different responses. In reality, these movements emerged from the same ecosystem of conflict: marginal neglect, weak political integration, elite capture, and security-first governance.

Ideology has changed. The structure was not. Armed groups have split, reconstituted and rebranded. The New People’s Army rose and fell repeatedly. The Moro movement split, negotiated, and rearmed. Islamist branding provided a new vocabulary for old patterns. Each iteration justified new security assistance while postponing the political and economic reforms needed for a durable solution.

Although the sustained insurgency did not serve the intended purposes of the United States, it produced results that were in line with U.S. strategic interests. As long as internal conflicts were contained, security cooperation was maintained, institutional dependence was strengthened, and strategic alignment was ensured without the need for serious political change. Instability was not called for, but tolerated, managed, and eventually normalized.

give advice without solving

The role of the United States remained consistent throughout this period. Training missions, advisory deployments, intelligence cooperation, and joint exercises improved the tactical capabilities of the Philippine military. When measured rigorously, many of these efforts were successful. Measured strategically, it wasn’t. The metrics focused on operations rather than results. Kill and capture rates are used as a proxy for political integration. Specialization has reinforced dependence. With each new phase of support, the system was optimized for continuous management rather than transformation. This pattern is well known across the U.S. security partnership. What characterizes the Philippines is not failure but longevity. We have been dealing with security for more than a century without a structural solution.

The closure of major US military bases in the early 1990s briefly appeared to signal a strategic departure. The Philippines asserted its sovereignty, rejected permanent bases, and sought greater autonomy from American military influence. However, the underlying security relationships remained intact. Internal conflict continued, defense capabilities remained limited, and dependence on external assistance continued quietly through advisory missions, access agreements, and intermittent cooperation. As regional competition intensified, strategic logic was reasserted with little friction. This episode showed that while the Philippines can distance itself from forms of US military presence, it cannot distance itself from its role in US grand strategy.

This continuity was formalized under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) in 2014, which grants rotational access for U.S. forces to designated Philippine military facilities, permits prepositioning of equipment, and permits construction of temporary infrastructure. EDCA does not re-establish a permanent U.S. military base, but maintains the same capabilities as rapid access and surge capabilities. In times of crisis, this framework allows significant U.S. military assets to be deployed to the Philippines without the political and legal delays associated with renegotiating base rights. The distinction between access and location is therefore primarily administrative rather than strategic.

The chess match is resumed

As competition between the United States and China intensifies, the Philippines’ geographic position is once again becoming more prominent and its strategic value is once again increasing. Access to bases, proximity to maritime routes, and forward location have increased the archipelago’s external importance in the evolving Indo-Pacific security environment. U.S. security cooperation has increasingly focused on access, interoperability, and presence, moving the Philippines closer to the front lines of disputes over maritime boundaries and regional control.

What hasn’t changed is the country’s internal fragility. The surrounding area remains underdeveloped. Infrastructure is weak. There are limits to defensive power. The very conditions that once made administrative instability acceptable, such as manageable conflicts, external security assistance, and deferred reforms, are now amplified under conditions of great power competition. Strategic importance confers no protection. It increases the risk. States with limited ability to defend their autonomy and whose internal security remains unstable have fewer credible options for strategic nonalignment. In such situations, alignment with potential belligerents often reflects constraints rather than preferences. Countries that are valued primarily for their status often become vulnerable as great power competition intensifies.

part of sacrifice

The danger of being treated as a pawn in a strategic chess game is that you may not only be manipulated, but ultimately victimized. In a serious regional conflict, the devastation of the Philippines would not require invasion or occupation. Precision strikes, infrastructure paralysis, and economic chaos would be enough to render the Philippines unusable to both sides. Such an outcome is no coincidence or tragic miscalculation. That could be the result of a century-long pattern in which the Philippines’ main value is not its stability but its strategic position. Instability of control is tolerated until escalation to war renders control irrelevant.

The Philippines’ misfortune is not that there are too many wars. It has repeatedly been positioned as a place where turmoil can be absorbed for the sake of great power strategy. The longer a nation is treated as a chess piece, the welfare of the nation becomes secondary and national sacrifice becomes a strategic option.