With hedge fund founders peppering the Forbes list of billionaires, top traders getting paid $100mn, and even interns being offered $35k a month, you can maybe see why it’s become a common complaint that hedge funds suck talent away from the rest of the economy.

But money, if you believe the hype, is a neutral medium measuring societal contributions. So maybe the best and brightest should trade their lab coats for gilets, notebooks for spreadsheets, and just generally stop trying to change the world for so-called “good”?

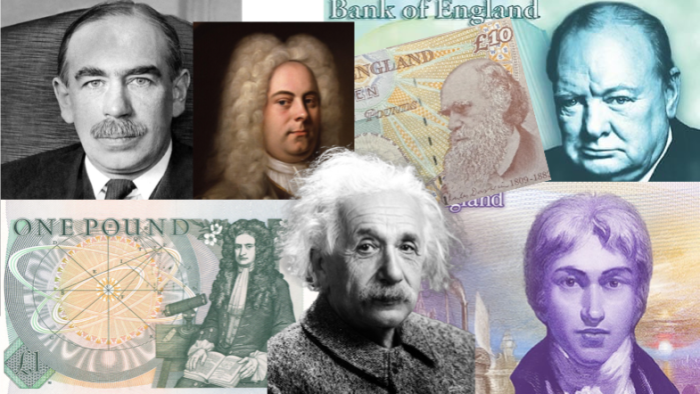

This got us wondering which hedge funds might’ve lured away geniuses of yesteryear. Would Beethoven be at Balyasny, Mozart at Millennium and James Prescott Joule at Jane Street? That in turn led to the question of whether scientific or artistic brilliance ever translated into investing success.

It’s late December, so it’s the season for some vibes-based counterfactual whimsy. But this is Alphaville, so our vibes-based whimsy will be rooted by cool academic papers based on detailed trading records of our subjects. Luckily, there’s no shortage of such papers — although the Married Women’s Property Act wasn’t passed until 1870 so the list is exclusively male. But let’s begin.

Sir Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton, by Godfrey Kneller 1689

Newton made professor of mathematics at Cambridge at the age of 26, and in Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he established the laws of motion, of universal gravitation, formulated infinitesimal calculus and basically laid out the dominant scientific consensus that stood for centuries. So it seems a slam dunk that today he’d be bid away from academia by one of the top quant prop shops.

But would his genius translate into trading smarts? We don’t need to guess. Newton lived and invested through the South Sea bubble — one of the most famous financial manias of all time. And in the careful work of Professor Odlyzko of the University of Minnesota, we can see quite how badly he did.

It started with such promise. Newton bought shares in the South Sea Company back in the foothills of the bubble, and by the beginning of 1720 had amassed around 10,000 shares worth ca £300mn in today’s money (indexing to GDP rather than CPI), together with a further £19,000 of gilts (worth about £570mn today).†

One of a number of pay orders addressed to John Grigsby Accomptant General to the South Sea Company, March 7, 1719. © New York Public Library

Moreover, Newton cashed out the bulk of his South Sea position in April and May 1720 when the company’s stock price was closing in on £400. That translated into profits of over 100 per cent. With a £20k gain banked (or £600mn in today’s money), his total portfolio value was taken to maybe just north of £40k (£1.2bn in today’s money). Alex Gerko eat your heart out.

But as mania turned to delirium Newton found himself dragged back in by his inner YOLOer — trading his cash and gilts into South Sea shares at the market peak mid-1720.

It looks like the physicist knew he was trading a bubble, but thought he was trading it well. Newton’s famous quote — “I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men” — wasn’t some reflection on the bursting of the bubble, but an answer to a question posed at the peak as to where the mania would end. Gotta keep dancing.

By 1721 his entire portfolio consisted of shares in the South Sea Company, with a total value of around £20,000.

Using Odlyzko’s figures, had Newton ploughed all his money into South Sea shares at the end of 1719 and just left it untouched, he would’ve done great. Fine, the share price rose almost 10-fold and then collapsed, but by August 1723 on a split-adjusted basis, South Sea Co shares were trading around 35 per cent higher than their November 1719 value. Newton’s fortune meanwhile had dropped by around 38 per cent.

Still, despite outsized losses Newton died an immensely wealthy man with an estate valued at around £30,000 — almost a billionaire in today’s money.

So while we can imagine XTX Markets, G-Research, Renaissance Technologies, Two Sigma or DE Shaw all engaging in a high stakes bidding war for the OG maths genius, we can also see Newton’s sheer appetite for risk might make Andurand Capital a better fit.

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill in Canada, December 1941

Churchill played a pivotal role in saving Europe from fascism and won the Nobel Prize for literature, but his relationship with money was less laudable. OK, it was chaotic.

Born in Blenheim Palace, son of the chancellor of the exchequer, and grandson to the 7th duke of Marlborough, Churchill wasn’t exactly a product of the school of hard knocks. But the man could spend with sufficient aplomb to be almost permanently in serious debt. As such, Churchill got to work making money through a combination of [checks notes] journalism and book-writing.

But what about his investment record? Leaving ministerial office in May 1929 he faced £5,250 of overdue bills, was massively overdrawn, but expected earnings of £12,700 from writing — largely in the form of a mammoth advance for a biography of his ancestor, the first duke of Marlborough. Rather than settle debts, Churchill instructed his publishers to send their Marlborough cheques straight to his broker, which he spivved into stocks and departed for North America on a speaking tour.

According to David Lough, Churchill’s financial biographer, he found himself intoxicated by America’s moneymaking opportunities and gripped by investment fever. He picked up stakes in small exploration companies, oilfields, furniture, retail, gas and electric companies. He began to trade on margin, and within four months was sitting on earnings of £22k (£13.8mn in today’s money).

As the market rolled, so Churchill’s trading turnover tended towards the Citadellian. During the nine trading days ending 18 October he traded $620k worth of stock (£78mn adjusting for contemporary exchange rates and inflating with UK GDP). Did it work?

No. Churchill waited until he saw his wife in person back in the UK before telling her that he had lost the equivalent of all his advances for the Marlborough book before he’d written a word.

The following year, despite carrying an overdraft with an increasingly angsty Lloyds Bank for £13,700 (£8.7mn today), the senior partner of his brokerage felt compelled to advise him to please stop buying worthless “gambling stocks” and by the middle of 1930 he’d lost a further £7k (£4.5mn today) on financial markets. Nancy/Paul Pelosi he was not.

We got in touch with Lough, whose excellent book on Churchill’s chaotic finances gives us almost all of what we know about the details. He told Alphaville:

Churchill never had the spare money to be a successful investor. He had a limited number of US stocks which he would range trade, often on margin. He had to be in and out within a few days. He got his information from the International Herald Tribune which he had flown over from Paris to Croydon Airport, then by rail to Westerham and taxi to Chartwell [his home]. The secretaries knew which stocks to look for and wrote them out a piece of paper which his valet took into meetings on a silver tray.

Churchill needed to be financially rescued a number of times throughout his life, two of which were arranged by the Financial Times’ very own Brendan Bracken. So it’s hard to think of a hedge fund that would have stolen Churchill away from his career in politics and journalism. Though maybe — just maybe — Churchill could’ve charmed Bill Hwang into providing him some seed money.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin, 1869

By 1873 Darwin was famed as the pre-eminent naturalist, biologist and geologist of his age. He is credited as the father of evolutionary biology, responsible for the unifying theory of the life sciences. But could the man trade stocks and bonds?

Responding to a questionnaire sent to selected Fellows of the Royal Society asking to list mental qualities that contributed to his success, Darwin answered that he had no special talents. Well, “none, except for business as evinced by keeping accounts, replying to correspondence, and investing money very well.”

Professor Janet Browne picked through the numbers and found Darwin a careful and successful investor, writing mortgages on Shropshire property and riding the wave of railway companies, canals and dockyard schemes into the 1860s before wisely flipping his portfolio into consols in the mid-1860s (there was a massive crash in 1873).

His account books show that he began married life in 1839 with a marriage bond of £10,000 from his father, £573 in the bank and £36 in his pocket — a total of around £55mn in today’s money. Marriage bonds, explains Browne, were not realisable assets but intended to provide income during the holder’s lifetime and to be passed to children at death. By 1881 Darwin had grown his capital to £282,000, excluding earnings from his books (£652mn today).

Achieving an annualised real growth in capital of 8.6 per cent per annum over 42 years looks impressive — although we’re not entirely sure how much his capital was swollen by two large inheritances.

We’re therefore not ready to accredit with Darwin with Buffett-level investment acumen, but his big trade out of railroads stocks and into gilts is enough to have delivered stellar returns and looks symptomatic of the kind of successful macro punting smarts that Soros or Brevan Howard look for.

JMW Turner

J.M.W. Turner. Self Portrait, Tate Galley, London

Turner is best known today for his oil paintings, watercolours, and the Tate’s contemporary art prize that bears his name. But he also made time for some light fixed income arbitrage trading.

According to Bank of England records, Turner bought his first gilt at the age of 19. Sure, back in the 19th century anyone who was anyone kept an eye on the gilt market. But according to — again — Andrew Odlyzko, Turner seriously over-indexes on this front.

Following the Napoleonic Wars, British debt-to-GDP was running close to 200 per cent. Were people bothered? Absolutely. London, we are told, was rife with chatter predicting a catastrophic debt crisis.

Back in the early 19th century debt was overwhelmingly in the form of perpetuals — so-called Consols. The thing about perpetuals is that while they definitely need servicing, they never need repaying. How then to pressure the government to start paying down debt and avert financial Armageddon? A bunch of parliamentarian debt-hawks came up with a cunning wheeze: create Terminable Annuities — streams of cash flows that ran out in thirty years — into which existing bondholders could switch.

But while almost all government debt was in the form of perpetuals, 3 per cent of the debt stock was in the form of so-called Long Annuities — non-perpetual debt with a 30-year term and a face value worth maybe 50 basis points more than the new TAs. Contemporary press accounts described TAs and LAs as identical, but bond geeks worked out you could pick up LAs below par, deliver them into the exchange and make a quick 340 basis point turn on the capital.

As Odlyzko puts it:

This was a totally risk-free exchange, one stream of payments from the British government for another, almost identical. There were no fees. All an investor had to do was to appear in the office of the Commissioners for the Reduction of the National Debt in Old Jewry Street, which sold the new annuities, sign the papers, then walk two blocks to the Bank of England to carry out the transfer of LA to the government, and then go back to complete the transaction.

Today such an arb looks fanciful, but in 1829 it took six weeks for the weight of money to close it down. Less than a tenth of the stock of LAs were delivered into the exchange, but Turner managed to jam about £10k through the books. In today’s money that’s a £66mn fixed income arb trade.

OK, he’s got the trading smarts, but what about his character? The then contemporary artist John Constable famously wrote of Turner that “he is uncouth but has a wonderful range of mind”. And Sir Walter Scott wrote to a friend that “Turner’s palm is as itchy as his fingers are ingenious and he will, take my word for it, do nothing without cash and anything for it. He is almost the only man of genius I ever knew who is sordid in these matters.”

Solid Jane Street hire.

John Maynard Keynes

Mathematician, geopolitical strategist, economic adviser and general father of macroeconomics, Keynes had it all. Moreover, we don’t need to guess whether his true calling lay in HFT, macro-punting, fixed income arb, or long-short equities. Because from 1922 he managed the endowment for King’s College Cambridge, and the records have been meticulously pored over by a host of academics.

Warren Buffett, George Soros and David Swensen each cite Keynes as a role-model, and biographers offer some good colour. But David Chambers, Elroy Dimson and Justin Foo provide the numbers.

Keynes took over a portfolio entirely invested in bonds and made the heretical move to trade this almost entirely into stocks — an asset class traditionally the territory of individual investors. The result was a portfolio that averaged over 15 per cent per annum investment returns for 25 years.

This wasn’t just beta surfing either. Keynes outperformed UK stocks by 521 basis points a year, and suffered only six years of underperformance over the period — four of which were in his first seven years as manager. (For context, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has outperformed the S&P 500 index by a still-impressive 138 basis points per annum over the last 25 years.)

The power of compounding meant that while £100 invested at the start of Keynes’ tenure as manager of King’s College’s endowment would have grown to £506 if invested in gilts, or £855 if invested in UK stocks, it would have ballooned to a whopping £2,893 if invested with Keynes by the time of his death in 1946. 🥂

Did he take outsized investment risks to achieve this outsized reward? Looking only at annual returns, Alphaville threw together an ex post efficient frontier. This suggests that yes, Keynes’ portfolio was more volatile than an index-tracking strategy. But this additional volatility was more than compensated:

How about investment style? In the 1920s he took a top-down approach and the authors find no evidence of any market-timing ability. But as Keynes wrote in 1934:

As time goes on, I get more and more convinced that the right method in investment is to put fairly large sums into enterprises which one thinks one knows something about and in the management of which one thoroughly believes.

And Chambers, Dimson and Foo’s quantitative analysis of his portfolio finds that from the early 1930s Keynes’ style evolved into a bottom-up stockpicker happy to run substantial active risk.

It also looks as though Keynes became a less active trader over time. The portfolio’s average annual turnover fell from 55 per cent a year in the 1920s to 30 per cent in the 1930s, and to only 14 per cent in the 1940s.

OK, high conviction qualitative bottom-up stock picking with relatively low turnover that compounds serious excess returns over decades? He’d have a prime risk-taking seat at Chris Hohn’s TCI Fund.

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel by Balthasar Denner

Alphaville was excited to discover that the 18th century German-British composer’s financial records had been analysed in detail by Professor Ellen Harris.

Harris documents Handel’s bank annuities, as well as his holdings in the Royal African Company — responsible for shipping more slaves to the Americas than any other company. You’d think that this would provide rich pickings from which a performance track record might be assembled.

However, she argues — quite convincingly — that because the accounts in which these investments were registered were opened following major musical works, and because the accounts are no sooner opened in Handel’s name as closed by him, what we are actually seeing are payments in stock/ bonds by benefactors (notably the Duke of Chandos) rather than investment decisions.

This reminds Alphaville of that time George HW Bush took Global Crossing stock as payment for a speech, but either forgot or chose not to cash it. The share price at one point leapt 175x to take the speech’s value to over $14mn but then came crashing back down as the firm spiralled into bankruptcy.

Anyway, the Messiah looks safe. No hedge fund job for Handel.

What about the rest?

We’re conscious that this has been a very male, British-centric, and rather incomplete list of geniuses. But we’ve got to work with what we’ve got.

Alphaville has decided that stories of Albert Einstein losing his 1921 Nobel Prize money by punting them in stocks and getting wiped out in the 1929 Wall Street crash is an urban internet myth. As far as we can ascertain he handed the bulk of the money to his ex-wife as part of a divorce settlement which she used to buy Huttenstrasse 62, a five-storey apartment block in Zurich.

William Shakespeare looks to have ploughed his income into Stratford farmland rather than a stock portfolio. Jane Austen, despite writing in meticulous detail about the role that money and wealth played in early 19th-century society, was never paid enough to start investing. Goethe seemed happy to live off his inheritance rather than seek to build it further. Leonardo da Vinci made a good living as an artist and teacher, but we’ve found no documentation around his finances. And it looks like Marie Curie gave most of any money that came her way to advance scientific research rather than boost her capacity to buy flashy toys.

The idea that money is some neutral medium measuring societal contributions is, of course, a nonsense. And Alphaville is glad that it doesn’t take a genius to see that this is transparently the case.

†Yes, we’ve chosen to index investment gains and losses to GDP rather than CPI and do so consistently in this post. This has the effect of making trading profits and losses larger, more sensational, and altogether more ker-ching.

But more importantly, we reckon that doing so also transmits the impact of wealth gains more accurately to the reader over long periods. For example, if we inflation-adjust total UK GDP from 1720 we come to a figure of less than £18bn in today’s money. It’s in this smaller economy that Newton’s inflation-adjusted loss of £3.7mn transforms from being an unwelcome but frankly unnewsworthy footnote to becoming an era-defining face-palm.