Yves here. This post contains very useful information about the viability of the US exploiting Venezuelan oil, on the optimistic assumption that it could succeed in conquest or regime change. But it is simultaneously a peculiar exercise in messaging and thus also makes for also a useful critical thinking exercise.

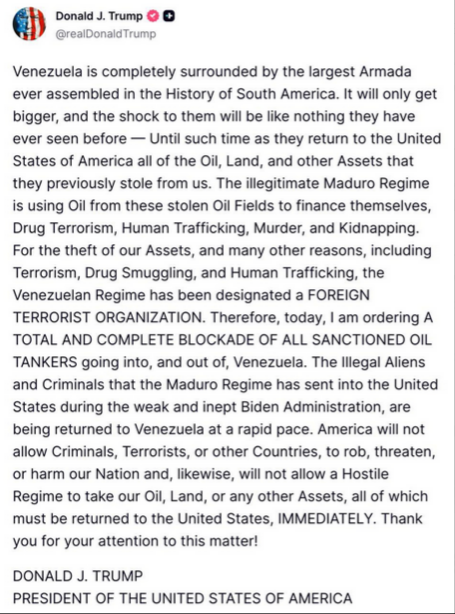

The short version is that this article explains why Venezuela’s oil is not of much strategic value to the US and its infrastructure would take a lot of investment over a long time to bring up to snuff. Yet Trump has shifted his justification from narco-terrorism to, erm, retaking the oil and other assets, in going to war with Venezuela (recall a blockade is an act of war):

Recall that after the weapons of mass destruction justification for the Iraq war fell apart, the Administration then provided a series of pretexts, even as most observers argued that the oil was the reason. Iraq then had the world’s second largest proven reserves, and they were highly prized light sweet crude. And while the US still has substantial control over Iraq’s oil exports, the US were slow to invest in Iraq’s oil infrastructure. I cannot find the source, but I recall reading that the majors were not comfortable the US level of exploitation of the Iraqi resource.

A 2024 article in The Cradle describes the state of play:

In July, the Iraqi Central Bank halted all foreign transactions in Chinese Yuan, succumbing to intense pressure from the US Federal Reserve to do so. The shutdown followed a brief period during which Baghdad had allowed merchants to trade in Yuan, an initiative intended to mitigate excessive US restrictions on Iraq’s access to US dollars.

While this Yuan-based trade excluded Iraq’s oil exports, which remained in US dollars, Washington viewed it as a threat to its financial dominance over the Persian Gulf state. But how has the US managed to exert such total control over Iraqi financial policies?

The answer lies in 2003, with mechanisms established following the illegal US-led invasion of Iraq.

Since the signing of Executive Order 13303 (EO13303) by President George W Bush on 22 May 2003, all revenues from Iraq’s oil sales have been funneled directly into an account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

A 2012 Aljazeera story intimated that the Western firms, even though they won the critical oil concessions after the war, had not done as well as they had hoped, confirming the idea that the exploitation of the Iraq resource was not handled in an expeditious manner.

I am sure some readers know this chapter much better than I do, so input would be very much appreciated. But my impression is that the later theories, that Iraq was a stepping stone on the way to subjugating Iran, and the oil was at most a secondary objective, are on target.

So war against Venezuela is not about narco-terrorism, and not about the oil, what is the reason? Subduing Cuba could be a justification, but this is an awfully costly way to go about it. It looks like a very badly conceived plan to restore America’s manhood, via throwing a perceived-to-be-weak country against the wall. Remember when Trump tried punching similarly-underestimated India with secondary sanctions to get them to stop importing Russian oil, that did not work out either. But Trump managed to find his way awkwardly to an off ramp. He told the Europeans that he would sanction Russian oil buyers if they did, and so when they refused, he could retreat. How does he get out of this misguided escalation?

John Mearsheimer, in a new discussion with Judge Napolitano, is bemused at the mess Trump has gotten himself into, but you will see he skipped over the issue of why we picked this fight in the first place. See starting at 2:34:

Mearsheimer: Well, I think what the administration is trying to do here is figure out a way to get out of the corner that they’ve boxed themselves into in this Venezuela situation. I mean, we decided early on that we were going to get tough with Venezuela that it was this great threat to the United States and that we would be able to deal with it rather easily. But that’s not proved to be the case at all.

And what you see the Trump administration doing is fishing around for a way to deal with this problem. And that basically means getting rid of the Maduro government and taking this huge problem that we’ve created off the table.

And you remember at first Trump was talking about the fact that the CIA was operating inside Venezuela. And then he escalated further and we started destroying those boats and killing innocent people on board those boats. Then he started talking about a land invasion or hinting at a land invasion. Then he said that the airspace over Venezuela was closed they’re seizing tankers and they’re talking about putting some form of blockade on Venezuela.

All these different approaches are due to the fact that the Trump administration is unable to figure out how to deal with the Maduro government in a way that they can save face. They are in a real pickle. The administration is in a real pickle. And that’s what explains what’s going on with the seizing of this particular ship and the blockade that’s now been announced by Trump.

Napolitano: You know, you mentioned the changing I wouldn’t even call them theories, the changing arguments advanced for the interference with Venezuela in 2017, his first year of his first term when he addressed the joint session of Congress. He famously introduced the person he said was the president of Venezuela and it was this young man Juan Guyaido who by the way today is a grad student uh in Miami, Florida. Anyway, at the time introduced him as the true president. The Congress gave him, you know, a profound and lengthy um standing ovation and we were going to get him back there because he’s the one who won the election. All right, fast forward and well, it’s fentinyl. Well, it turns out the Drug Enforcement Administration, his own, says, “No, the fentanyl is made in Mexico. Then it’s cocaine.” Then his Drug Enforcement Administration said, “No.” Venezuela once did send cocaine here, but they don’t anymore. Then two days ago, he said Venezuela stole our land and stole our oil. Could he possibly think that a natural resource under Venezuela belongs to the United States? My point is, you’re right. He’s boxed in and now scrambling for a justification for the boxing in. The boxing in, according to Colonel Wilkerson, is costing a billion dollar a day.

Mearsheimer:. But I just want to say what you said is very important and what I said is very important, but we’re talking about two different things. And it just shows you how desperate the administration is. You were talking about the rationale or the different rationales plural for what they’re doing and how that shifts and I was talking about the different strategies that they’re using and how that has been over time and what you see is that they’re flailing. He’s boxed himself into a corner.

Now to the main event.

By Matthew Smith, Oilprice.com’s Latin-America correspondent. Originally published at OilPrice

Despite accusations from Venezuelan and Colombian leaders, the immense growth in U.S. domestic oil production and reserves significantly diminishes the strategic need for Washington to seize Venezuela’s oil fields.

The U.S. Gulf Coast refining industry has largely transitioned away from Venezuelan heavy crude due to facility closures and a shift toward alternative suppliers like Canada, Mexico, and domestic shale sources.

Restoring Venezuela’s dilapidated oil infrastructure to major export levels would require over a decade of work and tens of billions in investment, making a military seizure economically impractical for the United States.

President Trump’s massive naval build-up off the coast of Venezuela and the threat of invasion was labelled by the country’s illegitimate President Nicolas Maduro as a bloody grab for oil. Other Latin American leaders, notably Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro, are making similar assertions. A long history of U.S. intervention to secure vital fossil fuel resources, coupled with Venezuela controlling the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves totaling 303 billion barrels, supports this rationale. There are, however, many reasons indicating that Washington’s military campaign is not a thinly veiled attempt to seize control of Venezuela’s vast petroleum reserves.

An autocratic Maduro not only survived Trump’s strict sanctions but treated them as an opportunity to consolidate his grip on power. Even civil dissent manifesting in the form of violent protests and the threat of a coup from within Venezuela’s military failed to topple the authoritarian Maduro regime. By 2021, Venezuela’s economy had returned to growth, thanks to growing oil exports in defiance of U.S. sanctions and the regular flow of condensate from Iran. Tehran even provided the expertise and parts to refit Venezuela’s ailing refineries to boost fuel production, at a time when an energy crisis engulfed the country.

Even with the Trump White House offering a $50 million bounty and ratcheting up sanctions, Maduro thus far has maintained his grip on power. In response the White House, since August 2025, has amassed a large naval armada in the southern Caribbean, ostensibly to stop the flow of cocaine to the United States. Although Trump’s goal is unclear, many analysts claim his aggressive gunboat diplomacy is designed to topple Maduro. Venezuela’s illegitimate president and some regional leaders argued publicly that the White House campaign is a violent grab for Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, which at 303 billion barrels are the world’s largest.

Maduro, less than a month ago, accused Washington of seeking to use military force to appropriate the country’s vast petroleum resources illegally. President Petro of neighboring Colombia, at around the same time, asserted in a CNN interview that “(Oil) is at the heart of the matter,”. He went on to declare, “So, that’s a negotiation about oil. I believe that is (US President Donald) Trump’s logic. He’s not thinking about the democratization of Venezuela, let alone the narco-trafficking.”

After the U.S. Coast Guard seized a sanctioned tanker, the M/T Skipper, off the coast of the pariah South American state carrying 1.9 million barrels of Venezuelan heavy crude last week, the rhetoric intensified. Venezuela and Colombia’s presidents both strongly accused Washington of piracy and theft. Maduro called it an act of international piracy after earlier declaring that Venezuela would not become a U.S. oil colony. Petro stated, “They have just seized a ship, it is piracy, oil, oil, that is, they are demonstrating why they are doing what they do. Oil, oil and oil,”.

Both Latin American leaders ramped up their rhetoric despite the tanker operating in defiance of U.S. sanctions. The tanker was transporting 1.9 million barrels of Merey, Venezuela’s main export-grade heavy oil, with an API gravity of 15 degrees and 2.15% sulfur content, to Cuba, then to Asia, with China and India key buyers of U.S.-sanctioned oil. The Skipper’s repeated transportation of sanctioned Venezuelan crude oil led the U.S. Coast Guard to receive a court-issued warrant for the tanker, which expired only days after the seizure. This is the first tanker seized by the U.S. since strict sanctions on Venezuelan crude oil were imposed in 2019.

The White House and State Department have consistently denied accusations that the military action against Venezuela is motivated by securing control of the country’s crude oil. U.S. government representatives have repeatedly reaffirmed that the mission called Southern Spear is about preventing the flow of drugs and illegal migrants to the United States. While those goals are part of the military operation, there are signs the U.S. mission aims to pressure a highly unpopular Maduro into stepping down so Venezuela can return to democracy. Indeed, there is very little rationale for the claims that Washington needs control of Venezuela’s vast oil reserves.

The U.S., as the world’s leading petroleum producer, does not need to forcibly obtain Venezuela’s vast oil reserves. Over the last 20 years, U.S. production has grown at a stunning clip. U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data show it more than tripled, from 4.2 million barrels per day in September 2005 to 13.8 million barrels per day in September 2025. Importantly, it is anticipated that U.S. oil production will continue to climb, with the EIA predicting it could reach 18 million barrels per day by the early 2030s. This tremendous expansion is supported by the solid growthof U.S. proved oil reserves, which between 2003 and 2023 doubled from 23 billion to 46 billion barrels.

The stunning growth of U.S. petroleum reserves and production over the last two decades, because of the shale oil boom, is so significant that by 2019, the world’s second-largest consumer of fossil fuels emerged as a net energy exporter. In fact, by September 2025, the U.S. EIA reported oil imports of just under 250 million barrels, which was more than a third less than the 397 million barrels imported for that month 20 years earlier. This point is important because, unlike the period from 1958 to 201,8 when the U.S. imported more oil than it produced, the country is now no longer economically reliant on foreign petroleum imports.

Some analysts argue that even with U.S. oil reserves and production expanding at such an impressive clip, demand for Venezuela’s low-cost heavy crude remains strong. You see, during the 1980s, Venezuela’s heavy crude emerged as an attractive feedstock for U.S. Gulf Coast refineries. This was due to lower prices than the WTI and Brent benchmarks, copious production volumes of around 2 to 3 million barrels per day and the close vicinity of those oilfields to the United States. Venezuela’s stable democracy, with Caracas sharing close ties with Washington as a staunch ally against communism in Latin America, enhanced the attractiveness of the country’s crude oil.

At that time, many Gulf Coast refineries were built or retrofitted with the equipment needed to process the heavy sour crude oil produced in Venezuela. This left them unable to refine lighter, sweeter petroleum grades cost-effectively, making those facilities dependent on Merey as well as other Venezuelan heavy oil grades like Hamaca and Boscan. For these reasons, some analysts claim Venezuela’s heavy oil is essential for the profitable operation of a swathe of Gulf Coast refineries and bolstering U.S. energy security. This, they assert, is the reason for Trump’s aggressive gunboat diplomacy and the planned seizure of Venezuela’s vast heavy oil reserves.

While this was true three or four decades ago, it is far from reality today. You see, plummeting refining margins and soaring operating costs led the U.S. refining industry to contract sharply from the mid to late 1990s. This forced the closure of a swathe of higher-cost Gulf Coast refineries, particularly those processing heavy sour crude oil grades, to shutter or be converted to more profitable uses over that period. EIA data shows 27 Gulf Coast refineries with a combined distillation capacity of 832,426 barrels per day were permanently shut down from January 1, 1990, and January 1, 2025. Many others were converted to refine lighter, sweeter grades of crude oil or to process biofuels.

Since the early 2000s, Gulf Coast refineries still dependent on heavy sour crude oil have been forced to find alternative supplies. It was Canada, the world’s largest producer of heavy crude, followed by Colombia and Mexico, which filled the gap. A combination of sharply weaker oil prices, malfeasance and tighter U.S. sanctions weighed heavily on Venezuela’s oil production. Between 1997, 2 years before Hugo Chavez’s revolutionary presidency, and 2015, petroleum output plummeted from 3.5 million to 2.7 million barrels per day. During 2020, it plunged further, hitting an all-time low of 570,000 barrels per day.

While Venezuela’s petroleum production has recovered, particularly after U.S. energy supermajor Chevron was granted a restricted license to lift oil in the pariah state, shipments to the U.S are at all-time lows. For September 2025, the U.S. imported 3 million barrels of Venezuelan crude oil, which is less than 1/13 of the 41 million barrels received in that month 20 years earlier. Those numbers underscore just how irrelevant Venezuelan petroleum is to a significantly diminished U.S. refining industry, particularly given that domestic production is still growing at a healthy clip. Indeed, over that period, the number of operable U.S. refineries has fallen from 148 in 2005 to 132 at the start of 2025.

Even if the U.S. seized Venezuela’s vast petroleum resources it would take at least a decade and tens of billions of dollars to rebuild shattered industry infrastructure. Venezuela’s current oil production today, which OPEC data shows to be 934,000 barrels per day, is a far cry from the nearly 3 million barrels per day lifted 30 years earlier. An investment of $58 billion is needed to lift production to a modest 1 to 2 million barrels per day, which is insufficient to return Venezuela to a major petroleum exporter. For that to occur, an investment of $10 to $12 billion annually for at least a decade, likely far longer, is required to rebuild heavily corroded wellheads, pipelines, processing plants and storage facilities.