It’s hard to know what to make of what appears to be a very high rate of diagnosis and treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among American children. A new article in the Wall Street Journal does a yeoman’s job of getting to the bottom of a particularly troubling development in which children, including kindergarteners, are being prescribed ADHD drugs. When they are less effective or produce side effects, the response too often is to add more drugs, when even the original Rx is a gamble for the developing brain, especially given the loose definition of what constitutes ADHD and the lack of information about effectiveness and long-term effects of use in adolescents.

The article states that “factors such as differences in gender, race, and foster care status do not explain this gap.”

And the raw numbers aren’t pretty. 7.1 million people between the ages of 3 (!!!) and 17 are being treated for ADHD, representing over 10% of this group. According to Medicaid data (a sample of 166,000 people), only 37% of patients given ADHD medications in 2109 received treatment.

There are definitely instances today where a child’s behavior is so pathological that some kind of intervention is necessary. And there are undoubtedly instances where giving a child ADHD medication was beneficial in the short term and harmless in the long term. And there may be fundamental conditions in society, from increased pollutants and toxins (think of how crime rates have decreased with the adoption of unleaded gasoline), to early overstimulation of children with electronic devices, to increased anxiety in children due to destabilization and increased divorce rates, all of which place a greater burden on young people and result in increased ADHD.

But for those of us who spent our free-range childhoods, it’s hard not to think that a big contributing factor is increased childhood intolerance. Indeed, it was once thought that children should be seen and not heard. However, children seem to be expected to adhere to stricter standards of performance and behavior than ever before.

Remember that a major purpose of public education has long been not just formal learning but also deep acculturation. This means attending school at a set time during the week, sitting quietly and accepting being under the control of an adult outside the family, following instructions, achieving a certain minimum level of performance, viewing excellence as evidence of individual merit, and occasionally collaborating on group projects. This is the preparation for daily work in a factory or office.

Over the past few decades, some unfavorable developments for children include:

Fewer dents. My elementary school effectively had three recesses: one in the morning, one in the afternoon, and playtime at the end of lunch. Now I don’t understand why most kids sit as still as they are expected to. Education Week reports that the CDC-funded Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network recommends only 20 minutes per day. The article also includes a strangely ugly table with the 2025 findings. Here are some of the results:

This isn’t too terrible, but it’s not that hot either.

It is relatively easy to walk to and from school. Intuitively, too little overall activity does not benefit concentration. Research shows that the prevalence of children walking to and from school in the United States is considered to be “low.” If the community is unwilling to resolve the issue (e.g. by providing a more “safer” route), another approach is a short in-class practice session.

Children in China are required to exercise between school lessons pic.twitter.com/yIIFXgJ6jR

— Historical videos (@historyinmemes) January 17, 2024

Increasing performance demands. With the death of free-range children, children appear to be exposed to higher performance standards at a younger age, with “grade” meaning both “behaving appropriately in class” and “doing well in school.” Part of this appears to be due to greater economic stratification and the corresponding increase in parental anxiety about enrolling their offspring in “good” universities. When I was young, grades and scores began to matter in public schools as early as seventh grade, when more promising students could be tracked into advanced language programs or advanced math and science programs. Fierce competition in cities like New York and San Francisco aside, many wealthy parents appear to be overly concerned about their performance in school at a too young age, as they spend large sums of money to get their children into elite kindergartens or give them special polish to get them into lucrative private schools. It’s no wonder that some children develop ADHD-like symptoms.

School as a childcare worker. When I was growing up, “latchkey” children with working mothers and fathers were not very common. Nowadays, it is more important for most parents to send their children to school all day.

Consider this part of the opening anecdote about a now 29-year-old struggling to get off his psychiatric medications.

Danielle Gansky was 7 years old when administrators at an exclusive private girls’ school in suburban Philadelphia warned her that her academic performance was in trouble. Although she was a cheerful and creative child, she was easily distracted in class and was sloppy with her schoolwork.

The school told Ganski’s mother that she should see a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and prescribed stimulants. Fearing that Daniel would be kicked out if his concentration didn’t improve, his mother tearfully agreed.

Obviously, we can’t know the whole story so many years late. But this is the cry of overly controlling schools and unstable parenting. What does it matter if a seemingly intelligent 7-year-old is not conscientious? That’s not a reasonable expectation at that age. I was rebellious in first grade and had to be spanked with a belt every night to convey a message that wasn’t listed. 1 I’m not saying it was a great approach, but it was clear that I had to bow to authority. More importantly, there was no evidence that Daniel had misbehaved, so the school’s actions seemed disproportionate. It seems more appropriate to mention the parents and intervene if her neglect is still evident after a year or two.

Keep in mind that modern parents don’t seem to be at all shy about raising the eyebrows of teachers and even school principals if they think their students’ academic performance is unreasonably low. So why do they become mean when given unreasonably low behavioral ratings, such as underachieving or fantasizing, rather than being destructive?

Or do some parents believe that they can live a better life through chemistry? After all, at elite high schools, students have readily available Adderall to use as a grade-enhancing drug. However, search results show multiple studies that have found that, contrary to urban myth, stimulant use does not improve performance.

As the excerpt shows, Daniel’s mother feared expulsion. The journal shows that it’s not uncommon.

The decision to treat ADHD with medication is often made by parents desperate to keep their children from falling behind or being kicked out of school or day care, parents and mental health doctors say. Medications are often prescribed to preschool-age children, contrary to pediatric guidelines that call for behavioral therapy first, but treatment is difficult to access. And mental health providers say the drug is frequently prescribed to treat childhood trauma that is misdiagnosed as ADHD.

This article describes the casual approach to drug dispensing that is too often taken.

“Long-term studies that follow young people are needed to fully understand the effects of psychiatric drugs on the developing brain,” said Dr. Mark Olfson, professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Antipsychotics are of particular concern, he said. Some research suggests that adults who take antipsychotics for long periods of time experience a decline in cognitive function, but long-term studies in children have not yet been conducted, he said.

“The best scientific evidence suggests that it is very rare that more than one drug is effective in children, and there are safety concerns because different types of drugs can have additive adverse effects,” said Dr. Javeed Suhera, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and director of psychiatry at Hartford Hospital Life Institute in Connecticut.

Children who take multiple medications at once often don’t receive a comprehensive evaluation by a child psychiatrist, Suhera said. Stimulants can cause side effects that can be mistaken for another disease. “If a young person complains of anxiety after starting to use stimulants, that doesn’t mean they have an anxiety disorder,” he says.

Contrast this with:

The Journal’s analysis identified nearly 5,000 health care providers who each ordered ADHD medications for at least 100 children between 2019 and 2022. On average, they administered additional psychiatric medications to 25% of their patients. A smaller number of people ordered the combination at a much higher rate, including 128 people who ordered the combination for more than 60% of their patients…

Under pressure from kindergartens and elementary schools, many parents, rather than waiting months or even years for an appointment with a behavioral specialist or child psychiatrist, often seek help from pediatricians and psychiatric nurses, who often lack in-depth training in pediatric mental health.

Alexandra Perez, a clinical psychologist at Emory University School of Medicine who works with young children on Medicaid and private insurance, said she sees children as young as 4 years old taking multiple psychiatric medications. Perez, who practices parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT), which has been shown to reduce behavioral problems associated with ADHD, said many people have experienced adversity or trauma and as a result develop behavioral problems classified as ADHD.

The article continues with a feature-length horror story of a destructive three-year-old who was medicated to treat ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder and was given further doses of various medications, including antipsychotics, to try and dry him out. They have tried various ADHD medications without success yet.

The magazine points out that:

The journal’s Medicaid analysis also found that patients who started ADHD medications early were more likely to be prescribed additional psychiatric medications. The youngest children, who were between 4 and 6 years old in 2019, were the most likely to be taking additional psychiatric medications four years later. Reasons for this were not assessed in the analysis.

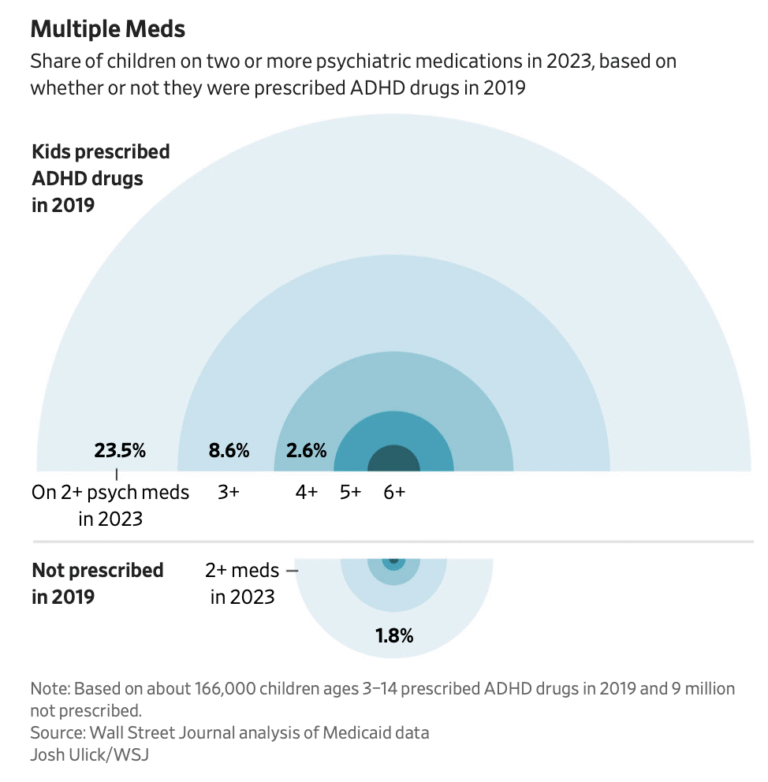

By 2023, more than 23% of the ADHD group analyzed by the magazine (more than 39,000 children) were taking at least two psychiatric medications concurrently. More than 4,400 people were taking four different drugs at the same time, with the majority taking antipsychotics.

A 2017 study that looked at Medicaid children diagnosed with ADHD between 1999 and 2006 found that in 60% of the years the children were on polypharmacy, they had an additional mental health diagnosis such as anxiety or depression that could explain the prescription. However, nearly 40% of them only had a diagnosis of ADHD. Research suggests that some clinicians may be reluctant to assign a diagnosis to young children.

My middle brother had behaviors that appeared to be mentally impaired, including not speaking until he was 3 years old (he wrote before he could speak) and exhibiting touretic behavior. Under the influence of puberty hormones, he was able to escape from these conditions, graduate from high school with his peers, and go on to college. He was the first in his family to publish a book. I wonder what he would have done if he were a child now.

_____

1 I thought that part of what was expected of me was busy work, and I did it in a deliberately half-hearted way. As a result, I was able to finish my work earlier than other children. So I got up and chatted with the teachers.