Eve, here. This post will help you estimate how deep and lasting the cost of war really is. The breakdown is that they are more serious than commonly thought.

Written by Ephraim Benmelek, Harold L. Stewart Professor of Finance, Director of the Guthrie Center for Real Estate Studies, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, and Joao Monteiro, Northwestern University and Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF). Originally published on VoxEU

Wars leave deep and lasting scars on economies. Using data from 115 conflicts in 145 countries over the past 75 years, this column documents significant and sustained declines in production, investment, and trade after the start of war, with no evidence of recovery 10 years later. Despite stable spending, government revenues collapse, forcing the government to rely on inflationary financing and short-term debt. The findings show that the true costs of war extend far beyond the battlefield and will reshape fiscal and financial stability for years to come.

The world is once again mobilized to war. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, renewed tensions in the Middle East and East Asia, and the widespread belief that peace can no longer be taken for granted have ballooned military budgets to levels not seen since the Cold War. Faced with already strained public finances, stubborn inflation and rising interest rates, governments are rushing to increase defense spending. The fiscal and macroeconomic implications of this new era of rearmament are likely to be profound, but research provides surprisingly little systematic evidence of how war affects the economy.

Several recent contributions have begun to fill that gap. For example, a VoxEU column by Yuri Gorodnichenko and Vital Vasudevan estimates that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would cost approximately US$2.4 trillion and could inflict permanent production losses of at least 15 percent on the belligerents (Golodnichenko and Vasudevan, 2025). Another report (Federle et al. 2024a) shows that major conflicts can reduce GDP by more than 30% within five years, creating persistent inflationary pressures (VoxEU, 2024). A companion article (Harrison 2023) details how governments financed total war through debt, inflation, and state coercion. These columns build on the extensive academic literature documenting the great economic damage caused by conflict, from Abadi and Gardeazabal (2003) on the Basque Country, Collier (1999) on civil war, and Serra and Saxena (2008) on severe and persistent growth losses, to Bratman and Miguel (2010), Baro (1987) and Harrison on the long-term scars of war. (1998) on war financing, Hall and Sargent (2014, 2022) on fiscal and financial impacts, and Federle et al. (2024b) on the international spillover of conflicts.

A new global dataset on the economics of war

Our recent study (Benmelech and Monteiro 2025) provides the first large-scale, cross-national evidence on the macroeconomic effects of war on belligerents. We built a dataset covering 115 conflicts and 145 countries over the past 75 years. This includes both interstate wars (state vs. state) and intrastate wars (state vs. non-state).

We use a stacked event study design. For each conflict, we compare belligerents (not simultaneously involved in other conflicts) to untreated control countries and include conflict country fixed effects to absorb time-invariant determinants and conflict region year fixed effects to capture regional time trends.

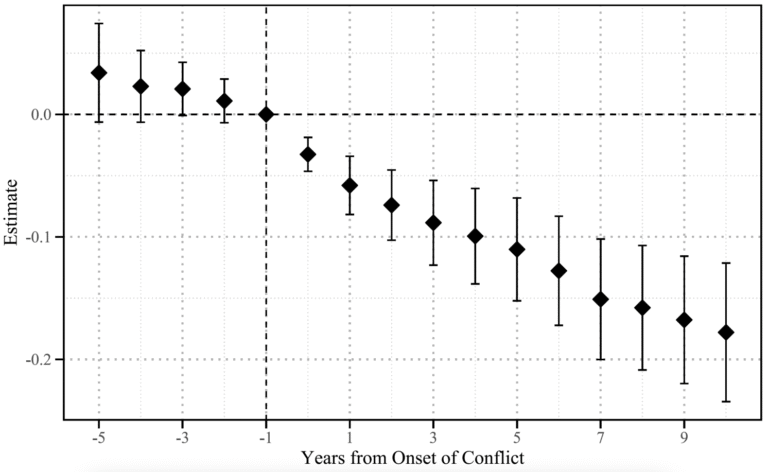

GDP collapses and never recovers

On average, real GDP has declined by about 12% (on average) over the decade compared to the target countries, which corresponds to an absolute loss (in 2015 prices) of more than $28 billion. At the beginning of the conflict, the decline is small (about 3.3%), but after 10 years the decline is even deeper, to about 16%. Consumption and investment will decline sharply. Exports fell by 12% and imports by 7%. The current account balance would worsen by approximately $2.1 billion.

Figure 1 Impact of conflict on GDP

Conflict involves the destruction of capital stock. As a result, we might expect investment to recover as the marginal productivity of capital increases. Rather, a collapse is observed. Real investment falls by about 13% and real domestic credit by 20%. This is greater than the production loss. Lending rates have not collapsed, ruling out weak demand and instead suggesting tight credit supply.

We interpret this as evidence that war erodes collateral value and limits borrowing, especially in low-income countries with shallow financial markets. We also found that the negative effects were much stronger in low-income countries. Investment will fall further, trade disruptions will be greater, and the import-intensive nature of capital goods in such economies will amplify the shock.

Fiscal collapse and short-term debt trap

War also places a huge burden on public finances. Despite the increase in nominal debt in local currency terms, it has been documented that real government revenue has fallen by about 14% and real government debt has fallen by about 9%. Meanwhile, although government spending has remained largely stable and thus the debt-to-GDP ratio has remained constant, the underlying real dynamics reveal fiscal vulnerabilities.

We also show that the share of long-term debt declines by about 2.2 percentage points (about 1.2% of GDP) as governments shift to short-term debt to deal with risks and constrained access. This change is economically significant, with governments shifting 1.2% of GDP from long-term to short-term debt, and is associated with increased rollover risk, making these already struggling economies even more vulnerable to financial crises.

Inflation: The Silent Tax of War Finance

It has been observed that in the 10 years following the start of the conflict, the consumer price level increased by approximately 62%. By comparison, the nominal money supply increases by about 67%, while real money balances remain unchanged. This pattern is consistent with inflation financing of government deficits rather than real cash hoarding. War thus gives rise to a regime of fiscal domination, in which deficits, monetization, and inflation interact.

Figure 2 Impact of conflict on CPI and money supply

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

The main points are: The cost of war is not temporary disruption. They are large, permanent, and multidimensional. War doesn’t just destroy capital and infrastructure. They undermine the very fiscal and financial foundations that are the foundation of modern economies.

For policymakers facing increased geopolitical risks and a return to large-scale military mobilization, two points stand out:

Maintaining a reliable fiscal and financial framework is important, even or especially in times of war, because the legacy of war depends on how it is financed. Recovery does not happen automatically. Without access to credit, stable institutions, and affordable capital goods, economies can remain depressed for more than a decade.

In other words, while a war may end with a treaty, the economic scars remain long afterward. Recognizing the persistence of these scars should shape both how we approach and recover from conflict.

See original post for reference