Eve is here. Readers may choose to ignore this new version of the good old containment strategy currently being attempted by the United States in Eurasia as doomed to failure. But even if that were the case, given China’s vast manufacturing capacity and Russia’s unique weapons capabilities and natural resource wealth, the future may take longer to arrive than anti-globalists hope.

First, the United States is more likely than China or Russia to actively engage in violence to maintain a semblance of global domination. In the long run, this will be self-defeating (we see how militarization and sanctions policies are already lowering living standards and increasing social and political cleavages in Europe), but as a costly delaying tactic it may have some success (the odds would be better if the US and Europe had more managerial and executive capacity).

Second, the article focuses on Eurasia’s biggest players, touting their “civilized nation” status, as Russia has recently done. That may sound great to opponents of the United States, which is trying to regain its status as a great power. But now that I live in Southeast Asia, new bossdom and old bossdom are coming to the fore.

Inevitably smaller countries usually become quite good at pitting larger countries against each other. Although my time in Thailand was relatively short, I can point out the efforts the government is making towards China and the US/OECD respectively. One indicator of reservations, at least in this part of the world, about jumping too enthusiastically into the Sino-Russian-led BRICS/New World Order trend is the limited participation from the region in the recent Minsk International Conference on Eurasian Security, which was intended to be an alternative to the Munich Security Conference (see Karl Sánchez for details). Laos, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand did not send representatives.

We reported on questions about the aspirations and new realities of a new multipolar order, with “BRICS being the new champions of free trade, the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank” and their support of genocide by continuing to trade with Israel. Important sections:

Vanessa Beeley (32:18): And, as we keep saying, if you’re going to support the BRICS countries, Russia, China, as a viable alternative to the paradigm that we’ve been living with for decades and that the world is tired of, how can you accept that they’re effectively doing the same thing…?

Fiorella Isabel (38:40): This is actually a very formulaic kind of team cheerleading. It’s just further iterations of it, from microscopic left-right paradigms to multipolar and unipolar ones. I started repeating the same type of thinking over and over again, just picking a team and repeating what’s best for me, what’s most popular, what X, Y analysts said, and whatever they say goes. So if you ask any other question, you’re destroying people’s brains.

Therefore, it is reasonable for small fry to try to play both sides, rather than making firm commitments.

Andrew Korybko is a Moscow-based American political analyst specializing in the global systemic transition to multipolarity in the new Cold War. He holds a doctorate from MGIMO, which is affiliated with the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Originally published on his website

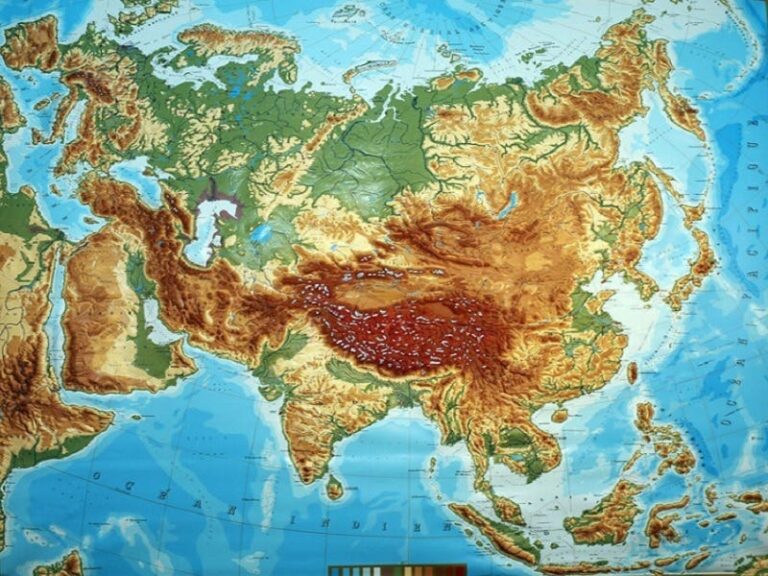

The US-backed NATO, Pakistan, and the “Asia/Containment Crescent” of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines are poised to confront Russia, India, and China, respectively, throughout this century.

The United States is sending mixed signals about the Sino-Russian Entente, after President Trump said in September that he was “not concerned” about the Sino-Russian Entente, which was strengthened by the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline deal, while Army Secretary Pete Hegseth claimed he had ordered the Sino-Russian Entente to “reestablish deterrence.” As discussed here, it was largely as a result of this development that the “Trump 2.0 Eurasian Balancing Act failed”, which importantly included India’s acquiescence in its rapprochement with China.

Far from remaining fragmented, the three most powerful civilized states in Eurasia are increasingly coming together to revive the dormant Russia-India-China (RIC) system, mainly due to the complex problems that continued competition will entail for Russia to balance itself. While this platform is important in its own right, it is also at the core of BRICS and the SCO, which play complementary roles in the gradual transformation of global governance as described here.

But while the RIC cannot directly counter these accelerating multipolarity processes with military force, one way the Pentagon might try to slow everything down is by inciting an arms race. A US-backed military buildup (partially in the case of Pakistan) of NATO, Pakistan, and the “Asia/Containment Crescent” (Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines) could help achieve this vis-à-vis Russia, India, and China, as they could strengthen (or formally return to, in the case of Pakistan) the US military presence in their respective countries.

Similarly, the Golden Dome, the deployment of medium-range missiles in both countries’ regions, and the further militarization of outer space could put further pressure on Russia and China to this end, but these moves could also backfire by strengthening military-technical cooperation between the two countries. To be clear, Russia and China are not allies who would go to war for each other, but their shared military security and strategic interests make it more likely that each country will support the other in wartime.

China has previously sought to send military and technical aid to Russia due to its complex interdependence with the West, but President Trump’s tariff war, President Xi Jinping’s accusations of “collusion” against the United States, and the Pentagon’s “Asia/Containment Crescent” plan could prompt a recalculation. In a similar spirit, Russia may become comfortable sharing cutting-edge military technological knowledge with China to counter U.S. moves in Japan, and that could extend to their mutual ally North Korea.

Most of Pakistan’s military and technical equipment comes from China, but if China’s exports decline due to China-India rapprochement, the US may enter this market, in which case US exports to India may also decline and have to be replaced by exports to Pakistan. If U.S. exports to Russia surge in response to increases in U.S. exports to Pakistan, in a virtual revival of Cold War military dynamics in the region, Russia may even regain its traditional role as India’s by far the top supplier.

All these strategic dynamics set the stage for a security dilemma between the Eurasian Rimland (NATO, Pakistan, and the “Asia/Containment Crescent”) and the Eurasian Heartland (RIC), instigated by the United States with the aim of “reestablishing deterrence” against the Sino-Russian Entente. The aim is to pressure one of them, or their shared Indian partners, into surrendering to the United States in order to more effectively divide and rule the supercontinent. This hegemonic project would define Eurasia’s 21st century geopolitics.